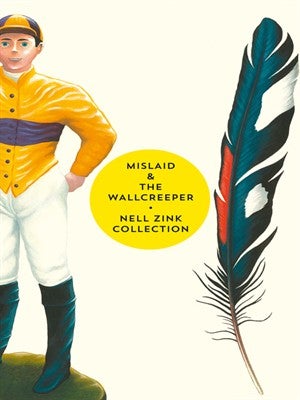

The Wallcreeper and Mislaid (box set) by Nell Zink - book review: Two of the most exciting novels I’ve read in a long time

Zink is a writer of astonishing verve and aptitude

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With timing so perfect it could have been plotted by the author herself, Nell Zink’s second novel Mislaid – a tale of racial transgression that employs confusion and coincidence like a Shakespearean comedy – reads like an equally fascinating and problematic addendum to the Rachel Dolezal case (the white civil rights activist). Fleeing an unhappy marriage (she was a young lesbian college student, he was her older gay professor – their adventurous but ultimately ill-advised affair was never going to last), Peggy steals the identity of a dead black girl for her daughter Mirielle, mother (renamed Meg) and daughter (renamed Karen) henceforth passing as African-American. “Maybe you have to be from the South to get your head around blond black people,” the narrator explains; this is 1960s Virginia of the “one-drop rule”: “If one of your ancestors was black – ever in the history of the world, all the way back to Noah’s son Ham – so were you.”

So far, so bonkers, right? But this bold new take on the classic mistaken identity plot is the zany world of Zink all over and Mislaid, crazy as it is, is also an ambitious and tightly plotted novel, a welcome successor to her dazzling debut The Wallcreeper (published in the UK for the first time in this boxset). A Bildungsroman featuring American newlyweds abroad – Tiffany and Stephen, who move from Philadelphia to Bern, then Berlin – it’s a sort of Grand Tour of birdwatching, eco-terrorism and infidelity that manages to be about female empowerment and environmentalism without any assiduous preaching.

When compared to the immediate and intimate tone of The Wallcreeper, Mislaid comes across as the more intricate of the two – a difference accounted for in large part by Tiffany’s first-person narration versus the omniscient third-person narrator of Mislaid. Artifice in all its forms is scrutinised in the latter volume; not even the prose or plot is exempt since it all adds up to the artistry of the whole. The Wallcreeper, by comparison, seems completely devoid of any pretence – honesty is the policy here, from the realities of anal sex, the mysteries of yeast, to fully embracing one’s true self. The same electricity fizzes through the prose in both books though: reading Zink is like receiving a series of shocks that jolt one’s sense of conventions and norms, from assumptions about narrative structure to political correctness: “I mean, I’m glad I grew up black, because it’s cooler,” admits Karen once she’s realised she’s Mirielle, “but it’s the white people who run the place, obviously.” Narrative downtime isn’t something Zink believes in either. Take, for example, the opening line of The Wallcreeper: “I was looking at the map when Stephen swerved, hit the rock and occasioned the miscarriage.” Eyes and ears must be constantly kept peeled as tucking significant plot points in subordinate clauses or throwaway sentences is commonplace: “And at some point after that he was dead.”

Much has been made of Zink’s unconventional path to publication, her years of manual labour, writing only for herself, her decision to not prioritise sexual or romantic relationships, not to mention her friendship with Jonathan Franzen – initially kindled over a mutual interest in birding, prior to him publicly championing her work – but strip all this away and she’s a writer of astonishing verve and aptitude. Her novels are two of the most audacious and exciting I’ve read in a long time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments