Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The publisher’s “advance praise” for Martin Wolf’s new book The Shifts and the Shocks is spectacular. According to the former Bank of England Governor, Mervyn King, the work is “masterly”. Larry Summers, the former Treasury Secretary, thinks it is “superb”. To Ben Bernanke, former Federal Reserve chair, the book is “insightful and timely”. After accolades like that from such a gallery of heavyweights a review seems almost otiose. Yet one senses that these paragons were offering advance praise for Wolf the writer and thinker, rather than this particular book.

Many grand newspaper columnists are overrated but Wolf’s reputation is deserved. The veteran chief economic commentator of the Financial Times has a unique talent for cutting through complexity and getting to the analytical heart of the big issues. These qualities, combined with his trenchantly liberal outlook, make Wolf a truly essential writer. But his books ‑ 2008’s Fixing Global Finance and 2005’s Why Globalization Works ‑ have tended to disappoint relative to his stunning newspaper pieces. And The Shifts and the Shocks, sadly, fails to break this pattern.

Wolf seems to get bogged down in the undergrowth of complexity that he so reliably hacks away in the pages of the FT. He feels the need to address, in rather numbing detail, every conceivable objection to his lines of thinking. There are, for sure, some typically wry lines. He notes that the slicing up and repackaging of debt by bankers in the boom years meant “risk had been distributed not to those best able to bear it, but to those least able to understand it”. The financial modellers of Wall Street “were clothed not in a silken weave of sophisticated mathematics and solid evidence, but in moonbeams”. The trouble is that these jewels are buried in an avalanche of closely-argued and heavily-footnoted text.

Unlike other feted economic tomes of 2014 such Atif Mian and Amir Sufi on household debt, or Thomas Piketty on wealth inequality, Wolf offers no novel theory in The Shifts and the Shocks. We learn that Wolf thinks banks should hold considerably larger capital buffers, that global economic imbalances are still a problem, that fiscal austerity in much of the advanced world has been misguided. He equivocates on the merits of so-called “narrow banking”, expressing the hope that some countries will try it out and, if it works, others can follow. This is, then, Martin Wolf’s familiar world view. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a powerful and important perspective, and I think it’s broadly right, but this is not a great vehicle for transmitting it to a wide audience. In truth, the general reader (and perhaps even the specialist) would be better off reading a choice selection of Wolf’s admirable columns over recent years instead.

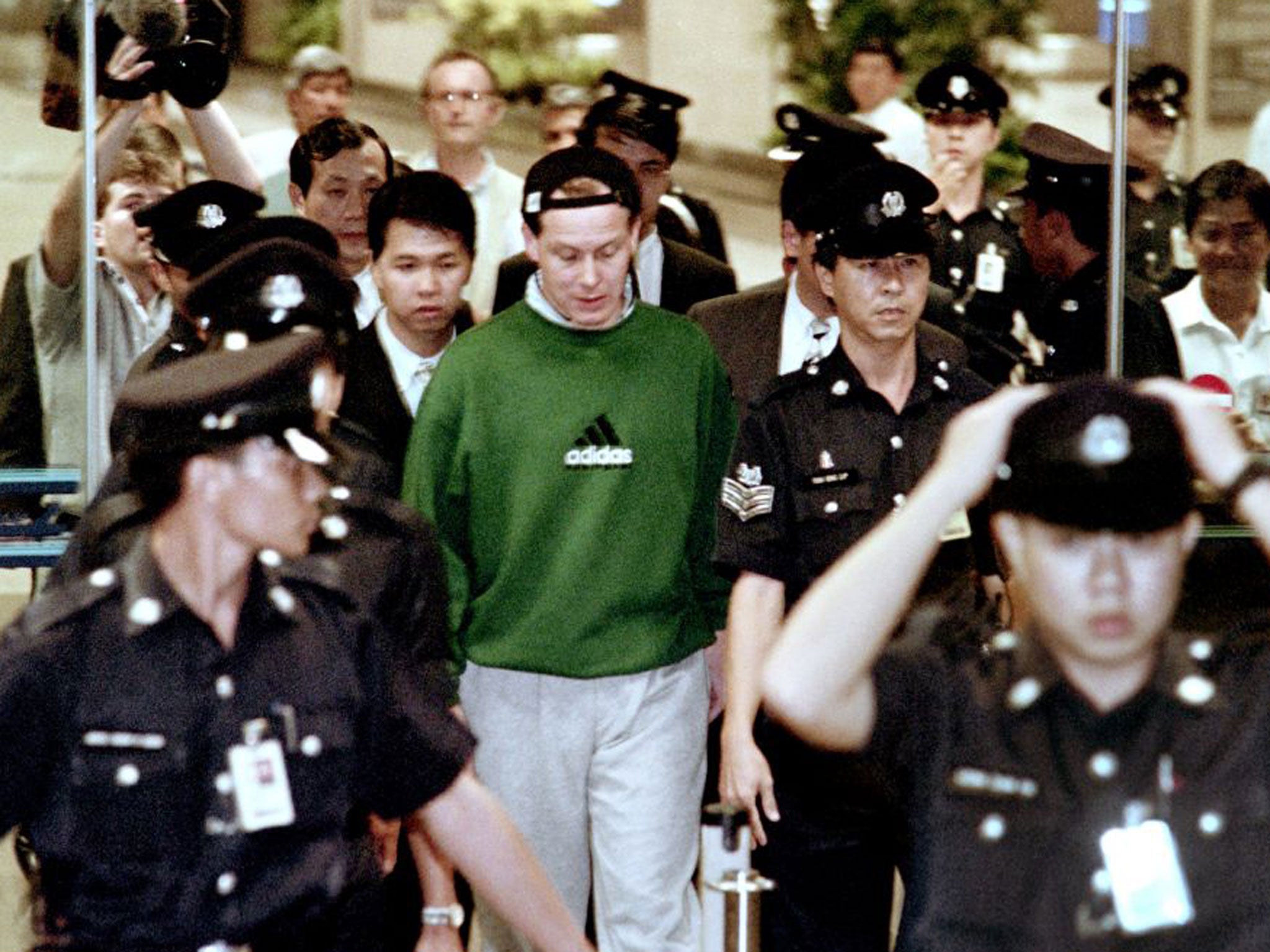

From the over-complicated, to the over-simplified. John Lanchester’s How to Speak Money feels like it was conceived as a “loo read”: an unchallenging tome that one might store in the smallest room for occasional perusal. Lanchester has built a reputation as a demystifier of finance. And there are some amusing lines in this book, which is structured like a lexicon of financial and economic terms. The Bank of England, for instance, “seems like a cross between Hogwarts, the Death Star and the office of Ebenezer Scrooge”. Yet I’m not sure what the reader gains from learning that Lanchester once met the rogue trader Nick Leeson on Newsnight and “liked him”. The book also feels rather casual at points. Lanchester says “it’s almost impossible to put into words” how big the global bond market is. Well according to the Bank for International Settlements the global bond market was worth around $100 trillion last year so that’s about 130 per cent of the world’s GDP. Wouldn’t that be more informative for readers than Lanchester waving his hands and saying the numbers involved are massive? Lanchester is right to say the general public need to understand money and finance better. But it will take a rather more exact book than this to close those troubling knowledge gaps.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments