Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

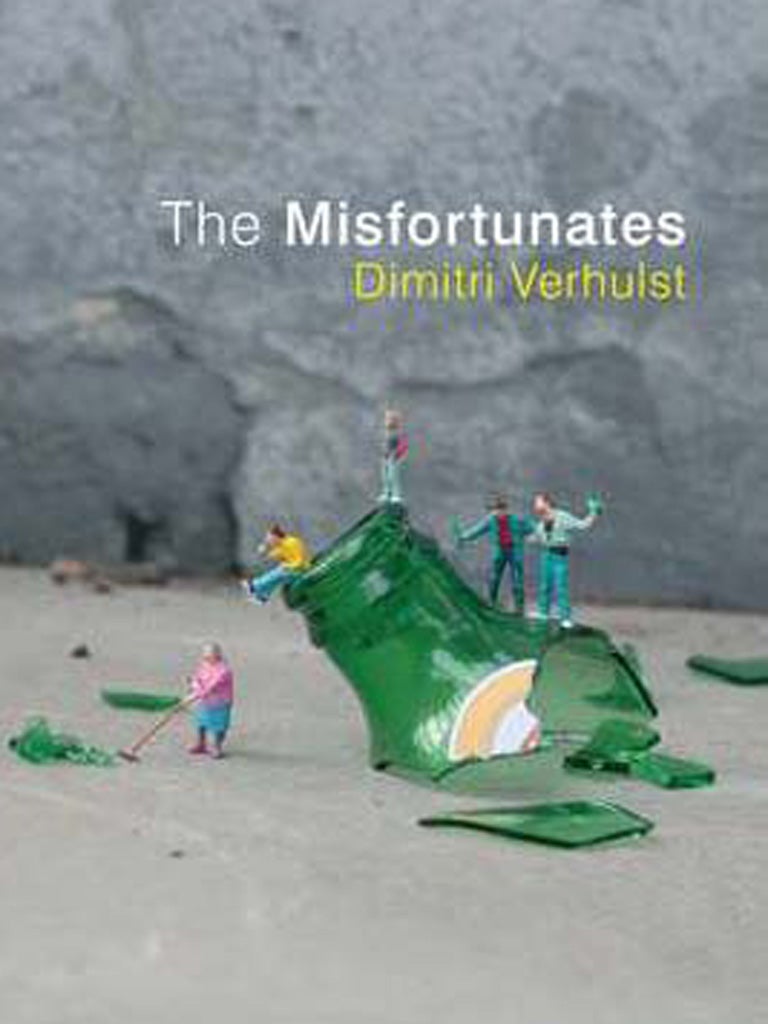

Your support makes all the difference.Reminiscent of the TV series Shameless in its portrayal of an anarchic working-class family, Dimitri Verhulst's semi-auto-biographical novel is set in a nondescript Flemish town, "an ugly backwater, but a great place for drizzle and pigeon fancying". It centres on the dysfunctional childhood of 13-year old Dimmy, who lives in his grandmother's house with his workshy, alcoholic father and equally inebriated uncles. Their squalid existence is worn like a badge of honour: "We were poor, always had been, but we bore our poverty with pride. A flash car in front of the house was a humiliation".

Everything in the Verhulst household revolves around alcohol consumption. When Dimmy's "respectable" cousin Sylvie comes to stay, the family delight in instructing her in the art of drinking. A social worker meets the family when they are suffering from a group hangover. The bailiffs attempt to repossess a television in lieu of defaulted payments squandered on beer.

The story unfolds through anecdotes where machismo, misogyny, and general debauchery are the dominant themes. The Verhulsts pride themselves on their proclivity for drinking, their sexual and fighting prowess, but what differentiates Dimmy is his powers of observation and ability to describe their lives with a wry, laconic humour.

Despite his family's aversion to anything resembling hard work, Dimmy makes a life as a writer. In the closing chapters, Verhulst fast-forwards to Dimmy's early experiences as an adult. His callousness towards the birth of his first child vividly contrasts with the devotion he shows to his grandmother in her care home. His affection for his late father remains, but his love for his uncles has been replaced with a mild distrust.

Turning degenerate lives into literature is nothing new, but Verhulst's distinctive voice, childlike and knowing at the same time, is particularly resonant. His savage humour is refreshing in its honesty. Seamlessly translated from the Dutch by David Colmer, this is a welcome addition to the ranks of literary fiction that find humour, and sometimes poetry, in urban deprivation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments