The Masque of Africa: Glimpses of African Belief, By VS Naipaul

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

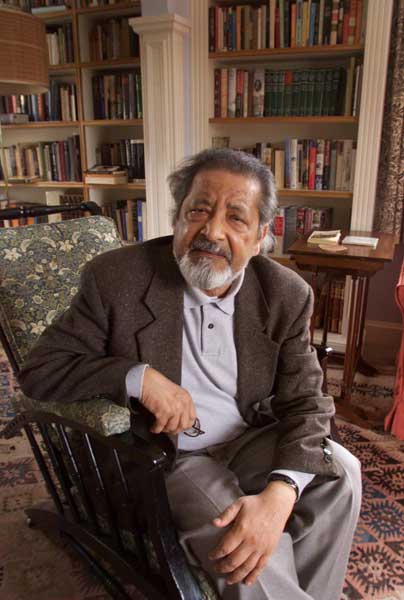

Your support makes all the difference.VS Naipaul always arouses intense loathing or unbounded exaltation, and smugly watches what he unleashes: to him, a sign he is invincible and a transcendent truth-teller. But time has taken its toll; his hands are shaky, his words no longer perfectly sculpted. The power over readers is dissipating, and a very good thing too.

Fans and foes will be touched by this book in unexpected ways. It is an account of a journey through Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Gabon and South Africa as he seeks out old beliefs and practices, from benign spirit worship to fiendish sorcery. There is vulnerability, trembling awareness of feelings beyond words, unprocessed ire we have not seen before, jumbled psychic wiring pushing him to the verge of something. It is as if a shaman stripped away his polish and flair.

Strong mixed feelings arise as you turn the pages. We know Naipaul as the lofty intellectual and consummate author, a knight and Nobel laureate; also as impatient, rude, misogynist and conceited: all bricks of a strong exterior wall, now guarded by his protective second wife.

The first breach in the defences was seen in Patrick French's authorised biography, in which Naipaul exposed himself with shocking honesty. His alter ego turned out to be Ralph Singh in The Mimic Men, a dislocated Indian Caribbean, needing affirmation, whose relationships with women were instrumental and heartless. Now, more of the writer is uncovered.

He seems to sense that. Naipaul has said he hoped the book would not cause a firestorm. Inevitably, it has. Novelist Robert Harris found it racist and toxic. Is it? Yes, and not quite.

There are many moments when one recoils from the behaviour, sentiments and observations: as when Naipaul claims that, with no early written history records, Africa has no intellectual foundations to build on; when he is contemptuous, tight-fisted, expecting five-star treatment and relishing meetings with the powerful and rich while often belittling them. He approves of Kojo in Ghana, an Ashanti aristocrat whose boys go to Eton. Richmond, his guide there, believes he has a Danish progenitor – the Danes were on the Gold Coast between the 17th and 19th centuries. Richmond is rational and analytical, traits Naipaul assumes had to "come down to him from the Danish ancestor, a man living by logic, full of internal resources".

Other prejudices roam freely, disguised as compassionate concern. He has a thing about kittens apparently maltreated and eaten by "barbaric" Africans, as are horses and dogs and guinea pigs, forest creatures. Any worse than the French, who love eating little songbirds and meaty horses? Long-horned cattle awaiting slaughter are "noble creatures, still with dignity, [which] await their destiny in the smell of death... with the beautiful goats and sheep... when sights like this meet the eyes of simple people every day there can be no idea of humanity, no idea of grandeur". Does he think our cows have Mozart played to them and walk into perfumed abattoirs?

Many are offended by Naipaul's focus on paganism. It is not racist to describe necromancy and witchery, which have a potency across the continent. To deny that is patronising and dishonest. Unfortunately, in this book, his recollections are of a chap on safari to see "pagan" people: the best wildlife now on the continent. Look how they cut off tongues of live people! Other bits, too! Whose bones are those they throw?

Though he evokes Heart of Darkness, Sir Vidia cannot take us down to Conrad's disturbing depths. Instead horror after horror is regurgitated until you feel you are at a bad Halloween party. It is sickening and meant to be. Sometimes he is pathetic, bathetic and careless – he tells us three times that the Bagandans, the biggest tribe in Uganda, built roads as straight as those made by the Romans.

However, Naipaul is an old chest now. If you go through it – not minding that your hands feel grubby – you find insights, clarity, reportage that combines the objectivity of a disaster photographer and an understanding of history. In Nigeria, for example, "hugging the shore of a creek was the great fisherman's settlement, a degraded Venice, shacks on stilts, just above the dark water which fed the shacks and which they in turn soiled".

There is empathy, too, for some places and for people like Susan, "a poet of merit" in Uganda, and others who share stories of brutality and retain a luminous humanity. The old Bagandan civilisation is beautifully described and in a forest grove, he experiences spiritual restoration.

He surprises most of all with his romantic musings on pre-colonial times, before Christians and Muslims spread their certainties and old authentic ways were destroyed or distorted. This will confuse those who say that Naipaul only feeds old colonial masters with stories of post-colonial failures. You feel he is trying to come to terms with a continent he finds unsettling, and always has done. He says that Gandhi, when in South Africa, "had trouble with Africans; he found it hard to see them, fit them into his world picture". Paul Theroux once described how his then friend Vidia "had a fear of being swallowed by the bush, a fear of the people of the bush".

Both these flinty writers were at Makerere University Uganda in the Sixties, then a hub of intellectual and artistic life. I was a student there, and used to loiter outside the Trinidadian's bungalow, a literary groupie. He gave voice to the first Indian diaspora, which until then had lived and died in obscurity. His people, like mine, had been wrenched away from India to faraway places, their original identities lost in transition. Some of the best writing in the book is when he describes African "betweeners", Western educated and culturally peripatetic – just like himself.

Theroux and Naipaul have each made return voyages to the Africa they once knew. Both are enraged by the devastated, littered landscapes. For Theroux the rot is the result of institutional malfunction, aid policies and political failures. Naipaul mostly blames the "fecundity" of the people and implies they are indifferent to filth in the environment. You begin to see why Derek Walcott said of Naipaul that "he is scarred by scrofula and repulsion towards negroes".

But there is chaos under the repulsion. The writer is an incomplete man, a searcher. The brown Sir, with glittering prizes, seems still afraid of the Third World that made him. No witch-doctor can banish those demons. Those haunting doubts and longings make this one of Naipaul's most stirring books, though he will not thank me for saying that.

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown's 'The Settler's Cookbook' is published by Portobello

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments