The Lover's Dictionary: A Novel, By David Levithan<br />Kama Sutra, By Vatsyayana, trans. AND Haksar<br />The Art of Love by Ovid, trans. Tom Payne

Last week I chaired an event at the French Institute during which Alain de Botton talked, with all his graceful erudition, about Stendhal's treatise On Love. For de Botton, that hopeless old romantic's wander through passion's rare peaks and frequent troughs adds up to a sort of autobiographical novel rather than a systematic theory of desire and disappointment. Lytton Strachey, he reminded us, thought that Stendhal combined the emotionalism of a 12-year-old girl with the rigour of a high-court judge. It's the quasi-legalistic side of his approach to amour that sometimes comes to the fore in the arch recipes and formulae of On Love.

Over millennia, male authors have shown a fondness for this kind of pseudo-system when writing about love. Heads might spin, hearts might pound, loins might throb – but dress up your infatuation as an under-the-bonnet user's manual or an auditor's report, and you can re-gain at least the illusion of control. This Valentine's Day, three titles show the perennial appeal of the literary urge to package the rules of attraction into gobbets, chunks and clauses.

In modern Manhattan, David Levithan has subdivided the highs and lows of an affair into a fictional "dictionary". It moves from "aberrant" and "abstain" to "yesterday" and "zenith". Each entry in this lover's ABC captures a pivotal incident or emotion along the road of a relationship between two mildly hip and kooky New Yorkers.

For all his tricksy ingenuity with form, Levithan's content never strays far from the hygienic breeziness of a mainstream Hollywood romcom. The author made his name with young-adult fiction. Although it does touch on some grown-up stuff – she likes sex whereas he often prefers reading; she comes from warring parents, he from a happy marriage - a pleasantly bland vanilla flavour suffuses the work.

Levithan wittily matches subject-headings with each section's content. But the detail tends to let him down. So the entry for "deciduous" reads: "I couldn't believe one person could own so nany shoes, and still buy new ones every year." First cute, then banal – like the novel as a whole. The Lover's Dictionary might work best for younger readers on the verge of the (mis)adventures it shuffles into snapshots, not for veterans who have been around the Manhattan block and already dipped into the ancient literature of love.

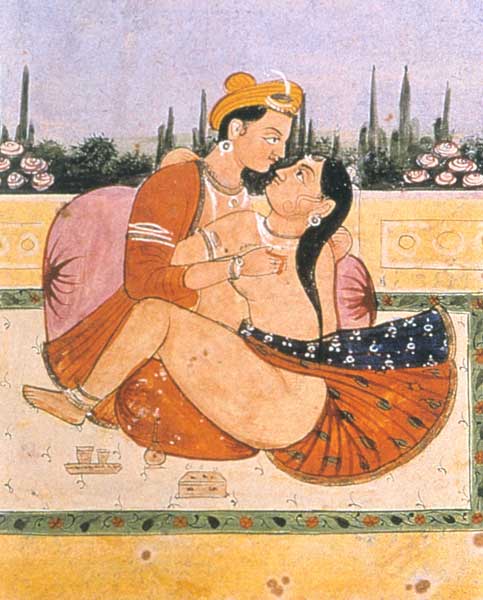

Cited often, read less, the Kama Sutra has stood as a landmark in that literature for more than 1700 years. The sage Vatsyayana probably wrote his Sanskrit "guide to the art of pleasure" near what is now Patna in Bihar in the third century AD. Thanks to the under-the-counter renown of a famous Victorian translation in 1883 by the leading Orientalist Sir Richard Burton, most people in the West think of it as a manual of sex techniques. Indian experts often dismiss this vulgar notion and evoke a philosophical account of good behaviour in courtship, love and marriage. As we can now discover from a scrupulous and accessible new version by the eminent Sanskrit scholar AND Haksar, both are right. Here sense and spirit, etiquette and foreplay, always intersect.

Vatsyayana writes for lovers, wives and courtesans living in a time and place of leisure, culture and elegance. Luxury gifts, subtle cuisine, expensive cosmetics, refined fashions: all fill the background of his prose and verse study of seduction, satisfaction and (with luck) serenity. For "The fruit of every kind of marriage/ Should be mutual love". His 64 ancillary talents associated with the art of love include "inlaying gems in floors", "mixing perfumes", "reciting difficult verses", and "knowledge of strategic sciences" – over and above the skills of assignation, rendezvous and finesse in the bedroom. He does keep his lovers busy.

This treatise fits sensual pleasure, Kama, into a scheme which also encompassed Dharma (virtue and morality) and Artha (wealth and power). It comes from a thoroughly forensic mind, and age, which can't observe a love-bite (would you prefer the "coral gem" or "piece of cloud"?), a sex toy or a flirty glance without slotting it into an exact classification. However modern-sounding the attention to women's pleasure in sex or autonomy in courtship, this trainspotter-ish drive to fix everything into its formal and cosmic place may strike readers as the book's most alien attribute – that, and a doggedly pedantic attention to biting, scratching and consensual SM.

Ovid would agree that Vatsyayana that "there is an aspect of conflict to sexual intercourse". He treats love as a contact-sport of high stakes and low blows. The Roman poet wrote his Ars Amatoria around 2BC-2AD. It may well have plunged him into hot water with Augustus, possibly via coded allusions to the emperor's frisky daughter Julia. Exiled to the Black Sea in 8AD, Ovid blamed an error and a carmen (poem). Is this the offending work?

Contrary to the naughty-naughty reputation over centuries of this much-banned how-to guide, only 40 lines in Book III deal with bedroom acrobatics ("If you've been scarred in childhood, don't display/ the marks; be Parthian – ride the other way"; the delightful notes gloss this as "reverse cowboy"). Addressed to men, Ovid's first two books cover methods of seduction and ways to keep your lover sweet; the third, for women, gives punctilious, slightly nerdy fashion, make-up, flirting and bedroom advice ("if you do fake, maintain the disguise; be sure to move about and roll your eyes").

With its jaunty, cunning and infernally clever rhyming couplets, Tom Payne's new translation is an utter treat from first to last. It follows the poet in his calculating but never wholly cynical pursuit of lovers – freedwomen were best placed – who would not fall foul of the prudish emperor's strict new laws against adultery: "Discreet seduction – safe sex – is my song".

Ovid trained as a lawyer. He shares with Vatsyayana that legal (or just male?) need to slice and dice the emotional life. And he likes to encumber Eros with tips and knacks, whether laying down the law for girls about the sexiest colours to wear ("let's lose the purple wool": too obviously pricey, apparently) or telling chaps how to avoid shaved-leg metrosexual narcissism and opt for "shabby chic" (but be sure to shun the "dodgy cut" up top).

Even if it's just self-interest, Ovid can sound like a new man as well as a sleazy cad. One size of seduction does not fit all: "Girls have such differing hearts. Thousands of minds require thousands of arts". Having wooed and won, lovers must keep on their toes: "Care and indulgence make people content – it's roughness and aggression they resent". Don't boast about your conquests ("In modern times we seek fame from a shag") or overstay your welcome ("Come when she wants; go when she wants no more"). Give as much pleasure as you take: "I hate sex when it brings uneven joys/ that's why I don't like doing it with boys".

As that couplet shows, Ovid's sympathies did have some, typically Roman, limits. Payne's commentary, and a sparkling foreword by Hephzibah Anderson, make the clear the deep gulf that separates his world from ours. Nonetheless, this effervescent Art of Love will be a lasting joy. For a while, in Book II, Ovid drops his zero-sum tactics and admits that happiness arrives once the hitched pair stops keeping score: "it's not a race where one of you prevails". On Valentine's, and indeed every other day, legalistic lovers would do well to mark his words.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments