The Kreutzer Sonata Variations, edited and translated by Michael R Katz, book review: The truth about sex and the Tolstoys

While the Russian novelist argued for abstinence, now we can read his wife’s response

In the late-19th century Russians were struggling with “the sexual problem”: how to deal with human lust with minimum oppression, misery, and offence to God.

Since we’re still all grappling with this one, even if for many of us God has dropped out of the equation, it’s worth revisiting the response to it of Russia’s greatest guru.

The Kreutzer Sonata is and was Lev Tolstoy’s most controversial work, which is saying a lot. Its protagonist reflects on how he came to kill his wife in a jealous rage, and concludes that sex is evil, there is no such thing as Christian marriage, and that everyone should aspire to be chaste even at the expense of the species. “Let it die out”, said Tolstoy in defence of his story. “I am no more sorry for the two-legged animal than I am for the ichthyosaurs etc. What I care about is that the true life should not die out, the love of creatures that are able to love.”

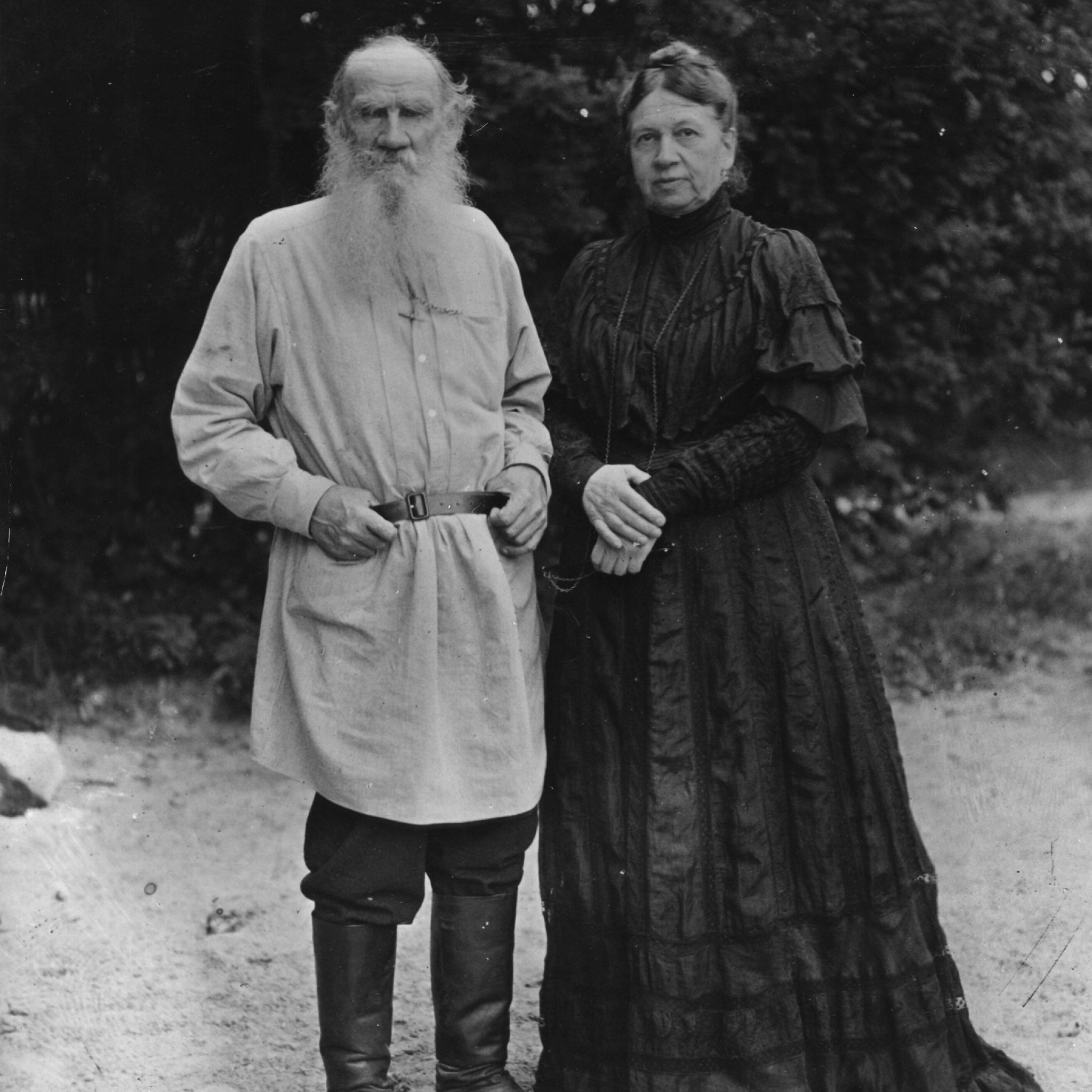

His wife of 26 years and 13 children was appalled, both by its message, and because it could be thought to be about her (and her close, not adulterous, friendship with their neighbour). She responded in two ways. She successfully petitioned Tsar Alexander III to un-ban it, thus implying her innocence while announcing her support. And she wrote a counter-story, translated here for the first time, called Whose Fault?, with marginal quotations from The Kreutzer Sonata highlighting the parallels of their plots.

Whereas the original leaves the wife’s infidelity uncertain, the counter-story focuses on the wife, who finds respite from an unsympathetic husband in unconsummated love for a noble, consumptive friend. The implication is that Tolstoy had been cynical in judging women by men’s standards, and that the answer to the story’s title question is “his”.

Four years later one of their sons, Lev Lvovich, published his own counter-story (also translated for the first time) called Chopin’s Prelude. It, too, disagrees with Tolstoy that all marriage is bad, and instead advocates early marriage for everyone, in order to avoid fornication. Like father, like idealistic son… In fact, the most striking thing about these stories is how many principles they have in common with their original, and how relevant these still are: denunciation of the double standard, of marriage as prolonged prostitution, and of the degradation of women into sex objects.

But we no longer think that lust is mainly male, nor that fornication and contraception are evil. We’re post-D H Lawrence now. We’ve reformed marriage so much that we’ve more or less left it behind; the unequal marriages of The Kreutzer Sonata and Whose Fault? are not only rare today, but fragile.

Yet, given the high emotional cost of serial monogamy, Lev junior’s solution of early marriage has a kind of appeal. Sofya wrote a second response to The Kreutzer Sonata, called Song without Words, about a woman with a kind husband who falls unrequitedly in love with a musician. To this kind of problem, no age has much of an answer, and Sofya offers none.

Together, these form a moving family collection. The fact that this beautiful edition has a foreword and afterword by living Tolstoys testifies to the very reproductive vigour which the title story denounces. It offers the best efforts of a formidably creative family at dealing with “the sexual problem” which both tormented and united them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments