The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, book of a lifetime: Magic rooted in reality of common life

The Jungle Books are continuous with Kipling's short stories for adults

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

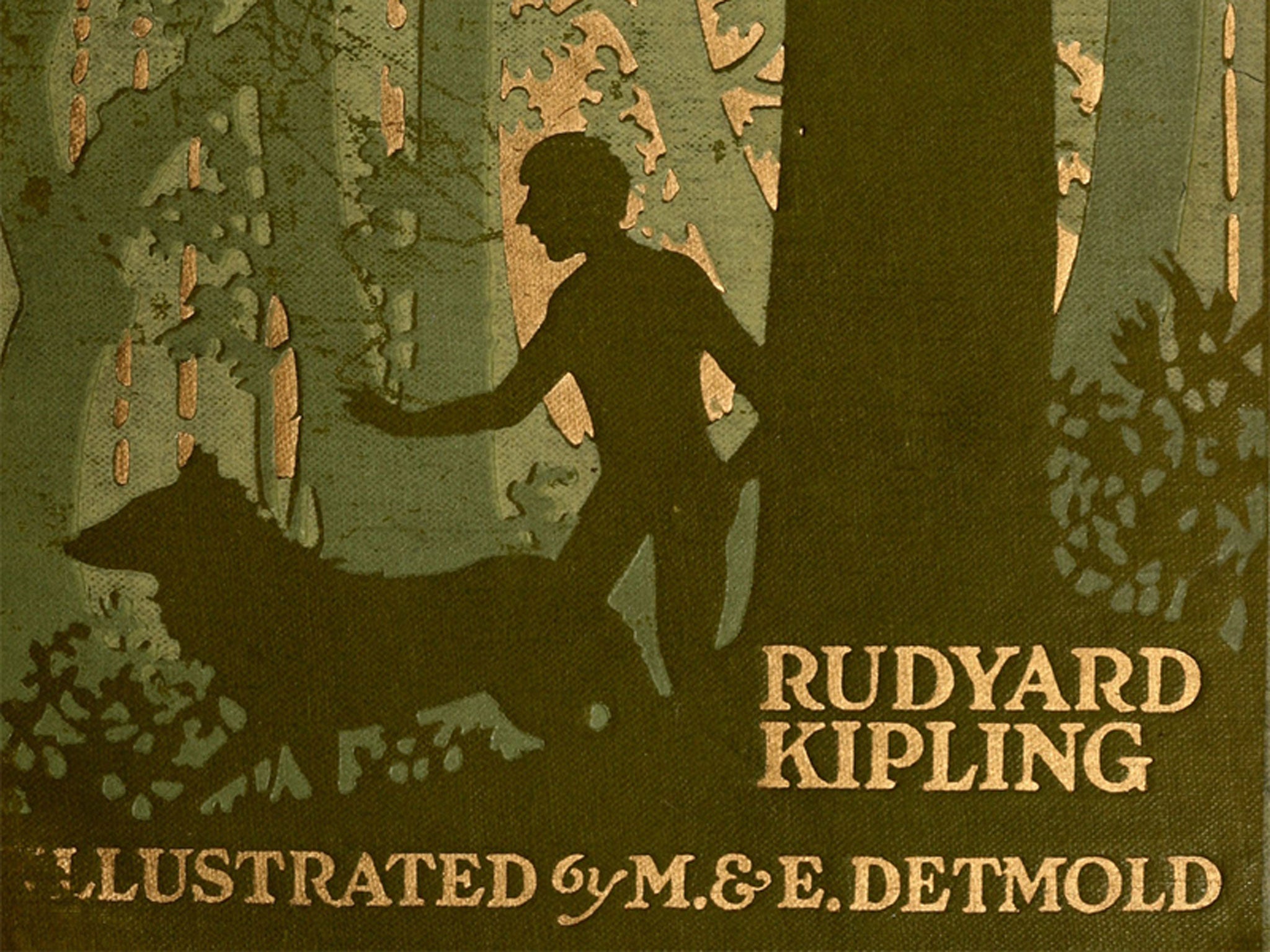

Your support makes all the difference.This was the first book I really lived. Almost from the moment I opened it, my pale goosepimples morphed into Mowgli's smooth brown skin and I was running through the jungle with my fellow wolf cubs to listen to Akela at the Council Rock. Those dark black-and-white illustrations (several of them by Lockwood Kipling, the author's father, who ran the old Lahore Museum, immortalised as the Wonder House in Kim) were mesmerising just because it was so hard to make out exactly what was going on in them.

Kipling's magic was always rooted in the reality of common life. All over India there were tales of a child reared by a wolf pack. In the background to the stories, village life goes on with its lazy rhythms – buffalo wading through the shallows, women going to the well. And further off you hear the harsher noises of Empire. Kala Nag, the elephant on whose back Toomai, the mahout's son, goes crashing through the jungle, carried tents and guns to the wars in Afghanistan and Abyssinia and hauled teak in the Burmese timber yards. When the escaped elephants meet in the forest for their dance which no man has seen, Toomai can hear the clinking of their broken leg-irons. I loved too the non-jungle story The White Seal with its brutal description of the clubbing of the baby seals, for – like all the best writers, for children as for adults – Kipling never flinches from the cruel things.

Then there are the songs, one at the beginning and end of each story. I knew most of them by heart once: "Through the Jungle very softly flits a shadow and a sigh – He is Fear, O Little Hunter, He is Fear!"

I can't suppress a twitch of rage at what Walt Disney did to The Jungle Book – enchantment and solemnity thrown away to make way for perky little cartoon animals squawking "the bare necessities of life". But then I suppose Sleeping Beauty suffered the same fate.

The Jungle Books (for there are two of them) are in a curious way continuous with Kipling's immortal short stories for adults. Those, too, are hard and beautiful, and when I first went to India many years later I found that, beyond the airports and the tower blocks, it was still Kipling's India.

Ferdinand Mount's 'The Tears of the Rajas: Mutiny, Money and Marriage in India 1805-1905' is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments