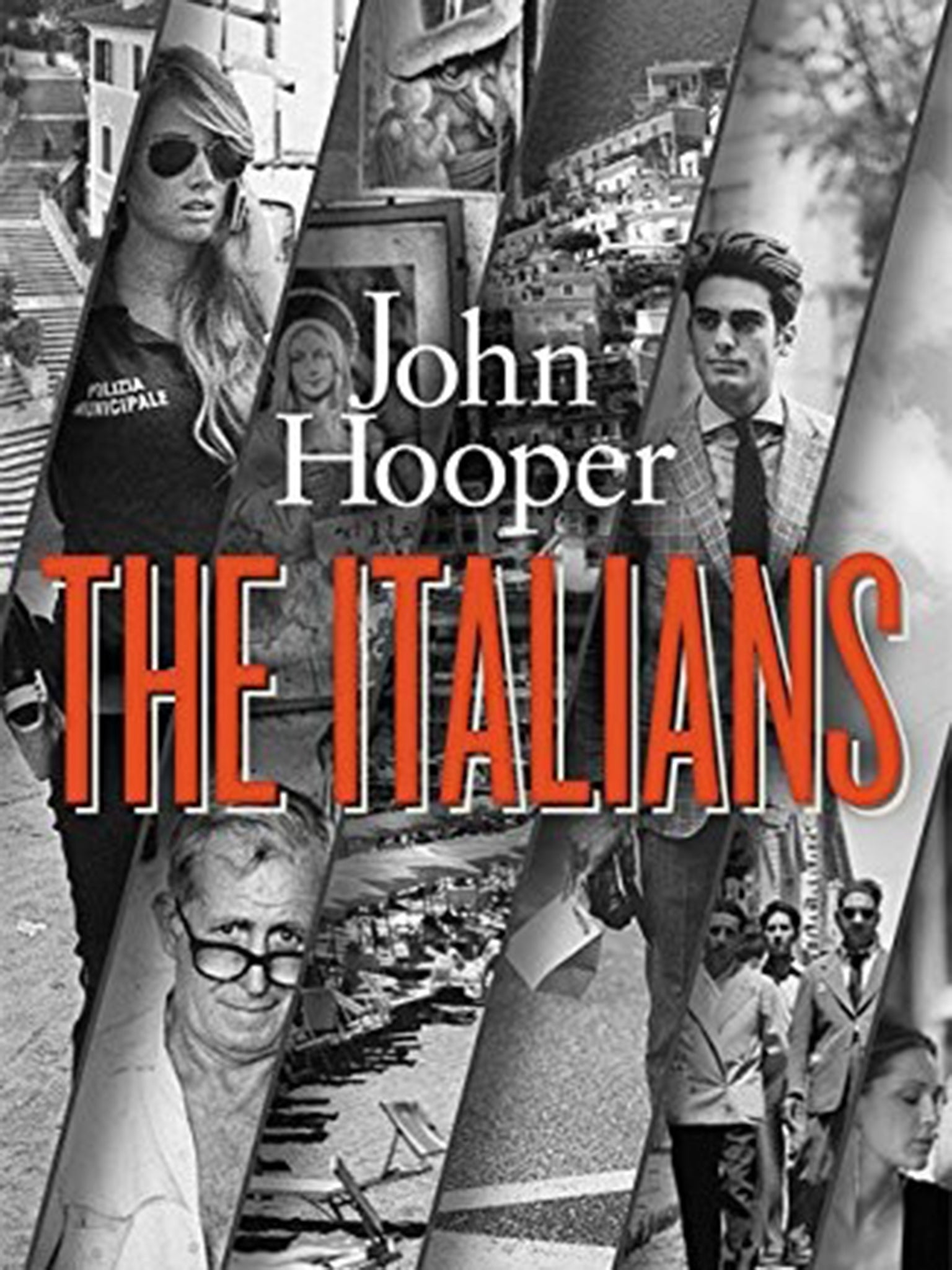

The Italians by John Hooper - book review: An Italy of pasta and pizza, but none of Mamma's rabbit

A conversational book that never delves too deeply into any topic but ready with relevant comment on almost everything

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What should we expect of a book with such a simple and seductive title?

A monstrous monograph on a nation’s whole history and culture, or a slim survey of that same ancient nation in this short century, a troubled member of the European Union? We are fortunate that we have neither, but in some 300 pages the author gives us some essence of the first, much reduced rather than distilled, and glimpses of the second viewed through a veil of whimsy rather than tedious high seriousness.

I turned to my schoolbooks for a sense of what The Italians might have been 80 years ago, to Methuen’s Italy; a Companion to Italian Studies, half as long again and deadly serious, for it struck me that as they were intended for untravelled undergraduates about to read modern languages, so could The Italians be. My old books were severely didactic (how times have changed), but this is a friendly book, first cousin to such talks on BBC radio as From Our Own Correspondent, ranging in a single chapter from Mussolini playing Potemkin when tidying Rome for Hitler’s visit in 1938 (to which I can add that his weeding the Colosseum did it more damage than 2,000 years of exposure to marauders and the elements), to finocchio, perjury, opera as an expression of nationhood, to cheating in exams and half a dozen other matters.

The author, with the fluency of the well-informed journalist (Hooper is Southern Europe editor for The Guardian and The Observer), writes as he might speak in conversation over dinner, never delving too deeply into any topic but ready with relevant comment on almost everything.

The book begins with three maps – one of Italy’s coastline, mountains and neighbours, without a single city marked, a second of Italy after the post-Napoleonic settlement of 1815, and the third, of the provinces of modern Italy from alpine Alto Adige to Sicily, a Herculean stone’s throw from north Africa. A fourth map – showing the kingdoms, principalities and Papal States that comprised Italy in the 18th century, the century of the Grand Tour – would have been useful as political and cultural background, but the Grand Tour, so influential in both Britain and Italy, the glue that still sticks us together, is nowhere mentioned.

Hopper then surveys the regions and their histories, the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy (but leaves the Guelphs and Ghibellines until 200 pages later), the local languages (languages, not dialects), and the imperial aspirations of the forgotten Agostino Depretis, Prime Minister between 1876 and 1887, who began the Italian occupation of Eritrea. Nothing, however, is said of the annexation of Libya in 1911-12, nor of Italian Somaliland, nor of Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia in 1935-36 – but then this is a history book only insofar as Hooper wishes it to be, and Mussolini, though a Leitmotiv of sorts, appears only as a clown or tragic figure. Much more attention is paid to Silvio Berlusconi as millionaire and mogul, magnate and machinator, his underpants and “bunga bunga” parties.

Food is explained, but only to the extent of pizza, pasta and olive oil; what the Italians can do with a rabbit, is not. So too bella figura (always dress well, even when seriously ill, always look seductive), football, family, freemasonry and the fabric of Italian life. Sex merits some observations – very different from mine (I have never elsewhere seen such blatant prostitution and knee-trembling in the open air and the nation still deserves its age-old reputation for sodomy). The divisions of the Mafia are neatly defined – the Camorra in Naples, Cosa Nostra in Sicily and ’Ndrangheta in Calabria, though they operate all over Italy and, indeed, anywhere corruption is rife. And why tolerate nepotismo, raccomandazione and sex for jobs and exam results? – because they work.

With the trial of Amanda Knox thrown in, and toy-boys, the European debt crisis, hand gestures, Fascism, the Second World War, the boom in plastic surgery and a history of the Jews in Italy – none in any depth – the reader must realise what a chatty book this is. The present-day Italian has not been formed by the land, its history and the traditions of Humanism and the Renaissance; he has no special relationship with the past – witness his selfish consent to its destruction in the environs of Venice (and imminently the city itself), and the industrialisation of the Po Valley and the outskirts of Rome and Naples; he has little interest in Italy as the economic giant that it could be, nor in putting her hand on the steering wheel of the European Union. John Hooper thus inevitably comes to no serious conclusion but has, as a journalist, written an amusing and engrossing account of a thoroughly irresponsible nation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments