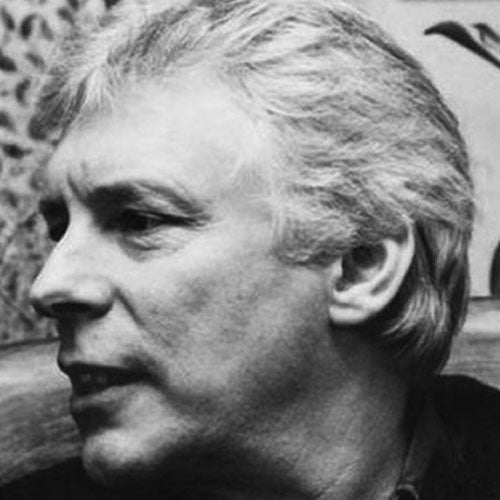

The Horseman's Word: A Memoir by Roger Garfitt

Fancy and folly of the man who fell to earth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Confession is a dangerous game. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the originator of the modern genre, received a fierce reception from which his serious political work never recovered. These days, we tend to praise Rousseau's sort of revelatory and self-reflexive openness. The bare-faced truths, pubescent fumblings for sexual and literary identities, dreadful poetry, humdrum drug-taking and the selfish vanities of youthful ambition make this endlessly fascinating literary mode still significant, and in some ways quite dominant. Yet the autobiographer still takes great risks in closing the space between a text and him- or herself. A negative reception might be received as a judgement of the teller rather than the tale. Unsurprisingly, Rousseau was paranoid even in his Confessions; lauded in some circles, Thomas De Quincey was demonised in others. Confessional narrators are brave people indeed.

The poet Roger Garfitt owes the likes of Rousseau and De Quincey a good deal. But his gentle, coaxing tour across the fervid climbs, lonely sloughs and frustrating plateaus of his early English years has a poetic delicacy of expression that neither of his progenitors could muster. His tour is guided by a sensitivity to natural history and a nostalgic grasp of a retreating, half-resentful post-war England. In moments of Wordsworthian contemplation, the prose lifts into a crisp and delicate conviction, and philosophical depth.

Garfitt is directionless, in the good sense that his self-mapping seems to have no manipulative intention. That this lack of direction is also a characteristic of Garfitt junior – the protagonist here – means that overall, the project of this book becomes unified. This is a study of a talented youth's desire for meaning, and is flighty and fickle as a result.

Garfitt maps his narrative of the first couple decades of his life through the regions that made him: Norfolk (with grandparents), Surrey (with parents and horses), Oxford and travels (as a student), and a brief coda taking him back to Norfolk. His development is written through the recovery of particular places, times of day or season, or shifts in the light or weather. The life story is threaded through visceral memories of self, and subsequent dislocations and alienations. This is a populous book too: a parade of characters sharpen scenes of intensity with the often enervating Garfitt.

Enervating, because for acres of this book, our hero is a picaresque fool: an idealistic 1960s student of alarming apolitical pretentiousness. He chases sex and poets and music like a long-haired jazz-dancing rabbit who has believed too much Keats and Kerouac. Our narrator, Garfitt senior, pretty much says as much of his younger self. Garfitt is crushed – though possibly not enough to listen – when he hears that a bitchy tutor at Oxford thought him "the most narcissistic person he had ever met". It is hard to disagree.

This autobiography presents a juvenile poet of jolting, angular earnestness. French children on the beach think Garfitt is a pop star. People spit at him for his hair, his hats, his colourfulness. In a memorable scene, David Bowie, dressed in recessive black, meets Garfitt, dressed in a daffodil yellow suit with blue pinstripe. Garfitt is a courageous confessor: "I should have had a card printed: Mistakes Made for You – Every Embarrassment Catered for".

But this fool is never comic, and is headed for something darker than laughter. Oddly enough, it is a strength that the longer the chain of febrile intensities stretches out, the less we can tolerate Garfitt's silliness and self-regard. As his drugged mind wanders, again and again, we become increasingly remote from him, worn out by his pointlessness, and his hormonal ordinariness. Until, that is, a huge mental crisis occurs, and the whole purpose and purport of this sad story changes.

What seemed like a desperate desire for attention from anyone suddenly becomes a garish and hopeless dance for an audience of one. In its final quarter, this book becomes deeply affecting as we watch a young man unable to cope with the sheer fluidity the 1960s entailed, at least for those willing to experiment with their own lives. Overall, The Horseman's Word is a searing act of personal confession.

Simon Kövesi is head of English at Oxford Brookes University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments