The Happy Marriage by Tahar ben Jelloun, trans. André Naffis-Sahely, book review: 'Living hell' for husband and wife

Tahar ben Jelloun's thumpingly ironic title fronts the tale of a long, fractious and toxic partnership

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tolstoy begins Anna Karenina with the questionable claim: "All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way."

If what applies to families also goes for the marriages that make or break them, readers of fiction may beg to differ. At least since the age of Tolstoy, Flaubert and Henry James, suffering couples in the novel tend to run to type.

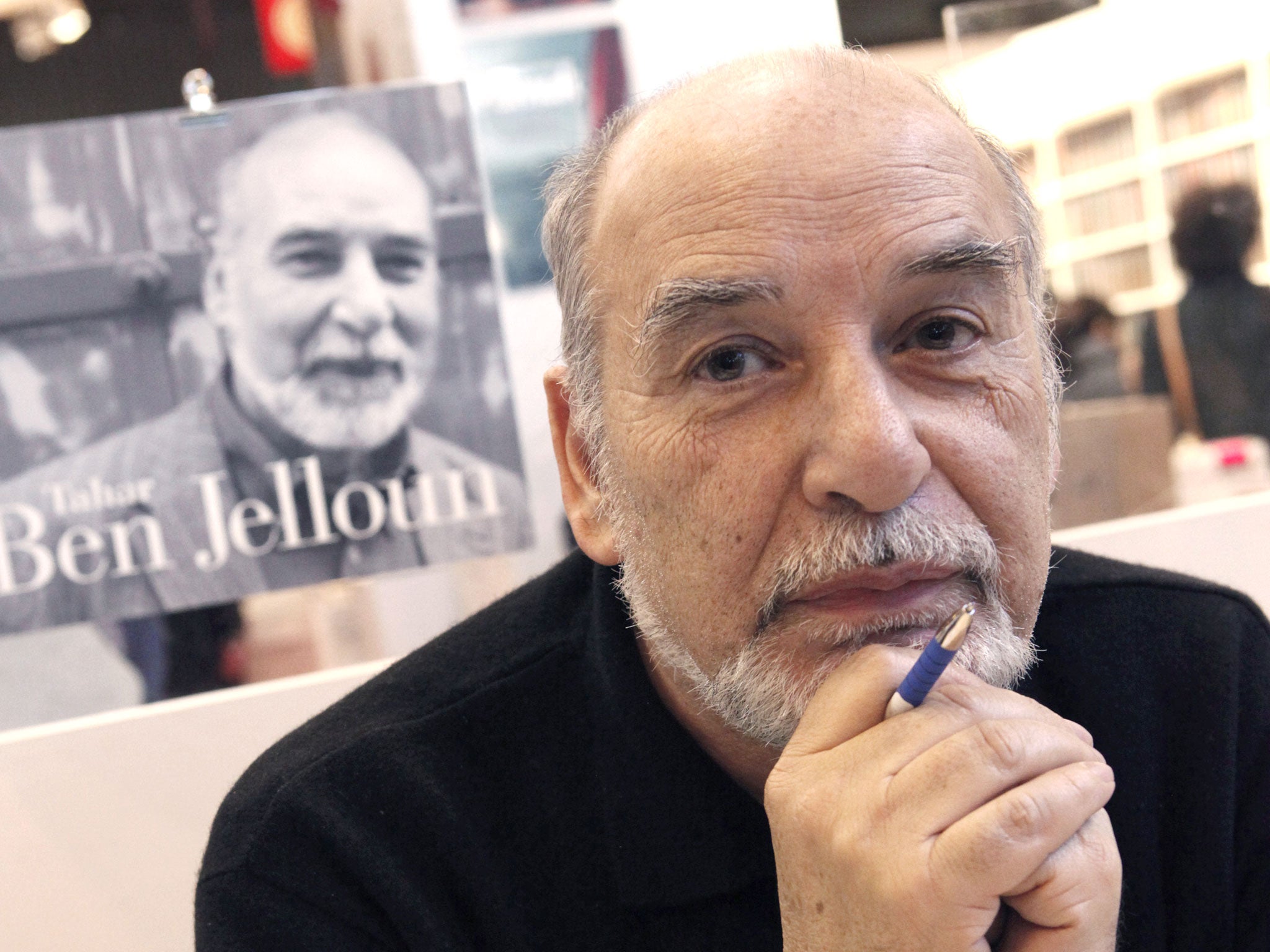

Tahar ben Jelloun, the powerful and prolific Moroccan-born novelist who migrated to France in 1971, knows all the pitfalls of his chosen genre. His thumpingly ironic title fronts the tale of a long, fractious and toxic partnership, a "living hell" for both husband and wife. The latter acknowledges: "We were not made to be together". So how does Ben Jelloun, always a resourceful and versatile storyteller, renovate this shop-worn material? Be patient, wait and see.

In 2000, a distinguished Moroccan painter has a serious stroke in Casablanca. Stricken by the immobility that diminishes him from a "brilliant, elegant and celebrated" artist to a helpless invalid who sees "a Francis Bacon painting" in the mirror, he has all the time in the world to reflect on his creative and emotional life.

His recovery inches forward at a glacial pace. Enlisting a friend as his amanuensis, he uses this enforced hiatus to compose a memoir. It swiftly descends into an embittered indictment of his wife, their relationship, marriage itself.

The painter comes from a wealthy upper-crust family in Fez – the snobbiest city in Morocco. His wife, much younger, is a wild, free-spirited Berber girl from a dirt-poor village in the south: beautiful, fiery, fearless. Chalk and cheese attract. Yet neither partner ever escapes this "clash of classes", as well as of temperaments. This fundamental incompatibility blights their wedding feast and then, as children arrive and his career blossoms, poisons their married life.

In this section, we see the relationship wholly from the painter's point of view. When he swans around the world and enjoys a succession of guilt-free affairs, he is "simply looking for some equilibrium". Yes, they all say that. More distinctive than his routine philandering is the painter's quest for truth in his art, fuelled by a "deep-seated aversion" to schools and trends.

Together, husband and wife fight like weasels in a sack. Ancient lore intrudes on this modern couple: each suspects the other of hiring black magicians. "Both of us," the errant husband admits, "have crossed a lot of lines". After a peculiarly savage row, the stroke fells him.

Ben Jelloun is too canny a narrator to finish only one panel in this portrait of a marriage. In the last part, the wife seizes hold of the story. Proud and defiant, quarrelsome but fiercely loyal, Amina reports that "I sprang out of rocks and prickly pears". Her version of events revises or contradicts almost every key incident.

Above all, she bears witness to the "unbearable humiliation" inflicted by her husband's serial infidelities. Her first-person testimony has a zest and punch lacking in the painter's more intellectualised apologia, with its nods to the conjugal horrors in Ingmar Bergman films. With a brisker swing to the prose, André Naffis-Sahely's translation also moves up a gear.

Amina plots revenge on "the monster who'd taken the best years of my life". Here, Ben Jelloun springs his clinching surprise: her vengeance will avoid all clichés.

In Amina's testament, The Happy Marriage makes good on the painter's aim to shun boring conventions. Finally, the novel resembles the works that – so she asserts – Amina's rejuvenating presence has allowed the painter to create. It becomes "lively, surreal, flavourful and human".

Melville House , £18.99. Order at £16.99 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments