The First Lady of Fleet Street, by Ellat Negeev and Yehuda Koren

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

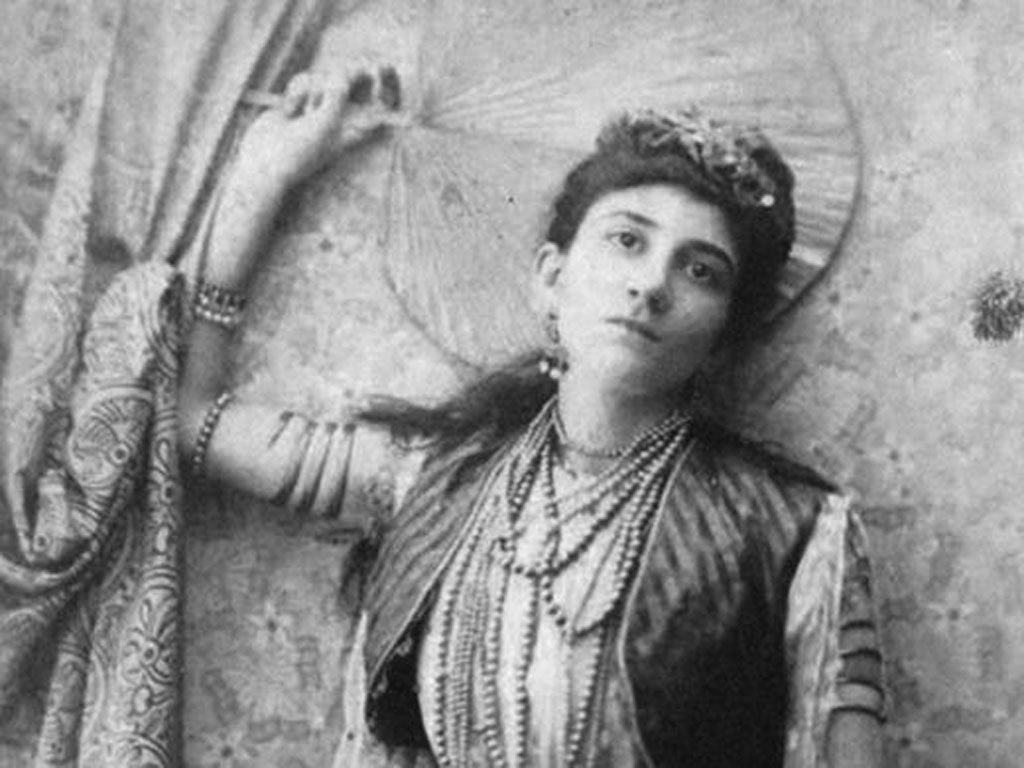

Your support makes all the difference.The "first lady of Fleet Street" was a perfect incarnation of Empire: the great-granddaughter of a Baghdadi Jew, whose son settled in Bombay, where he made a family fortune out of trading opium, Rachel Sassoon grew up wealthy in London.

Her husband, Frederick Beer, was also wealthy, but his family's money had come through harder means – via the Jewish ghettos in Frankfurt, until his father, Julius, settled in London and, with a group of others, bought The Observer. Julius himself would become rich enough to build a mausoleum to commemorate his dead daughter, Ada.

Indeed, there is as much tragedy in this story as there is wealth – both Rachel and Frederick lost their fathers at an early age, and Rachel was ostracised by her family when she married. Yet, heartbreaking as it was, her father's death probably benefited her – bright, independent and keen to be useful, she was free of any injunction to marry until she was ready. She set herself up as a political hostess in London, and, friendly as she was with the Gladstones, could have genuinely influenced how the government dealt with social causes. She called, too, for taxing the rich, and for better pay and conditions for the working classes, bringing this to The Sunday Times when her husband bought it and made her editor. More able to keep an independent voice because of her isolated position as a woman in a man's world, she excelled at the job. Frederick's early death, however, broke her, and she was declared insane, when really, she was simply grieving. A too-early end to a fascinating story.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments