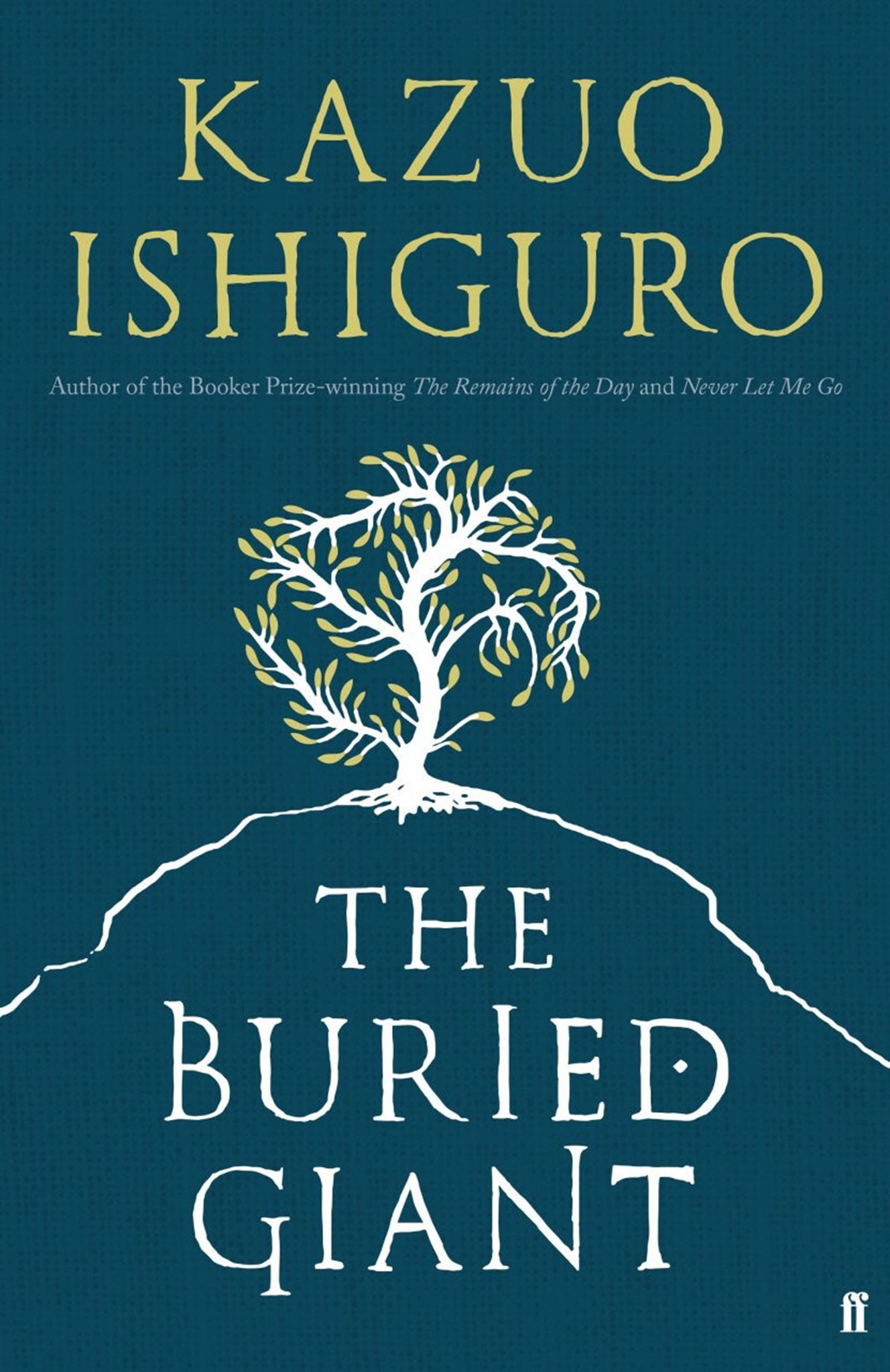

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro, book review: Don't fall for the fantasy: This novel is classic Ishiguro

The Tolkien-like world of magical creatures is a real departure from previous works

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ishiguro’s seventh novel – his first since 2005’s Man Booker shortlisted Never Let Me Go – touches on familiar themes.

There is the unreliability and subjectivity of memory seen in A Pale View of Hills and When We Were Orphans; the dreaminess of A Pale View of Hills; the repressed tragedy of The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go; the regret of A Pale View of Hills, The Remains of the Day and An Artist of the Floating World; and the pain of ageing or death of A Pale View of Hills, An Artist of the Floating World, and Never Let Me Go. So far, so Ishiguro. What is different is the setting – a land of ogres and dinosaurs. Some of his work has had an unreal air, but a Tolkien-like world of magical creatures is a real departure.

I confess, initially I was crestfallen, as I abhor the fantasy genre, but my fears were premature. As with so much of Ishiguro’s work, the superficial wrapper is not the main attraction. Ishiguro doesn’t deal with literal representations of life so much as allegory and allusion. And, in fact, humans and their fallibility are very much at the heart of this fable.

The story is set around the sixth century AD, when Saxons have arrived in Britain from their Germanic homelands. The legendary King Arthur has died some years ago, and although some residual bad feeling exists between Britons and Saxons, there is an uneasy peace. An elderly couple, Axl and his wife Beatrice, have been troubled for some time about their son, of whom they have only fleeting, misty memories. This partial amnesia is something suffered to some extent by everyone. Axl and Beatrice set off to look for their son, though they know the journey will be long and arduous.

Along the way, they meet Wistan, a Saxon warrior; Sir Gawain, an elderly knight and nephew of the late King Arthur; and other characters including a boatman who has sinister echoes of Charon in Greek mythology, who rowed dead souls across the rivers Styx and Acheron to Hades on condition that they had a coin for him.

Axl and Beatrice are gentle and loving with each other, and one of the reasons is that it’s impossible to hold grudges or nurse acrimony when incapable of forming and recalling memories. But they long to uncover recollections of shared times. The amnesia of their country folk similarly keeps the peace as it enables past battles to be forgotten.

Ishiguro’s unspoken question is whether this kind of collective amnesia can be justified, or whether it is more fair for people to face up to the ugly truth of past deeds, even if it means some will set out to exact vengeance.

Man’s crimes against man have been countless throughout history, and have similarly countless parallels in the modern world: Northern Ireland, Japan post-Second World War, the Holocaust, South Africa, Nigeria, the Serbian/Bosnian conflict, Rwanda, Iraq, Syria, Libya; often followed by bloody retribution. Without the fog of amnesia, Ishiguro’s tale shows, individuals inculcate others with their desire for revenge.

Even when people are aware of their past misdeeds, can they expect forgiveness? In a scene in a monastery, Wistan challenges a monk on the religious belief that prayer and self-flagellation will absolve crimes.

Ishiguro also touches on personal morals; the arbitrary decisions people make about what is acceptable behaviour. Harming people seen as “other” is often viewed as excusable, even when they have previously been friends. And, although the monks shrink from active killing, some are prepared to facilitate slaying by others.

Denial is another form of assuaging the conscience. Though a decent fellow, Gawain is loath to take responsibility for his actions, and is prone to paranoiac outbursts and projection.

But the writer does have some sympathy for those who embark on aggressive action and then realise they have made catastrophic mistakes: “Imagine ... how a shepherd must judge quickly, hearing a sound in the dark, if it heralds danger or the approach of a friend. Much must rest on the ability to make such decisions quickly ...”

And of course, such decisions depend on subjective assessment. As Ishiguro shows in the course of this tale, if even happily married couples can hold vehemently differing perceptions of shared memories or objects seen in the distance, how can we hope all to agree on the right course of action in relation to major issues? The buried giant of the title is an allegory for the buried hatchet; the repression of hatreds, resentments and the desire for violent redress. It prevents justice being attained, but also impedes the never-ending cycle of tit-for-tat.

Ishiguro’s prose is as spare, restrained, understated and formal as always, but beneath lie deep emotions. The ending, as so often with this writer, is all the more devastating for being so controlled.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments