The Boy at the Top of the Mountain, By John Boyne - book review: Corruption of youth in Hitler’s lair

Doubleday, £12.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Every story, one is taught as a child, has a beginning, a middle and an end. Some endings, however, are so good, so perfectly wrought, that they are absorbed into the pages before it, filling their flaws like cement in the cracks. In 2006, John Boyne achieved such a feat with The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, a book following the friendship between a boy in a concentration camp and the son of the Nazi commandant in charge. The novel was decent, but its ending delivered a perfect emotional climax and a final, devastating blow. Almost ten years later, Boyne hasn’t lost his touch.

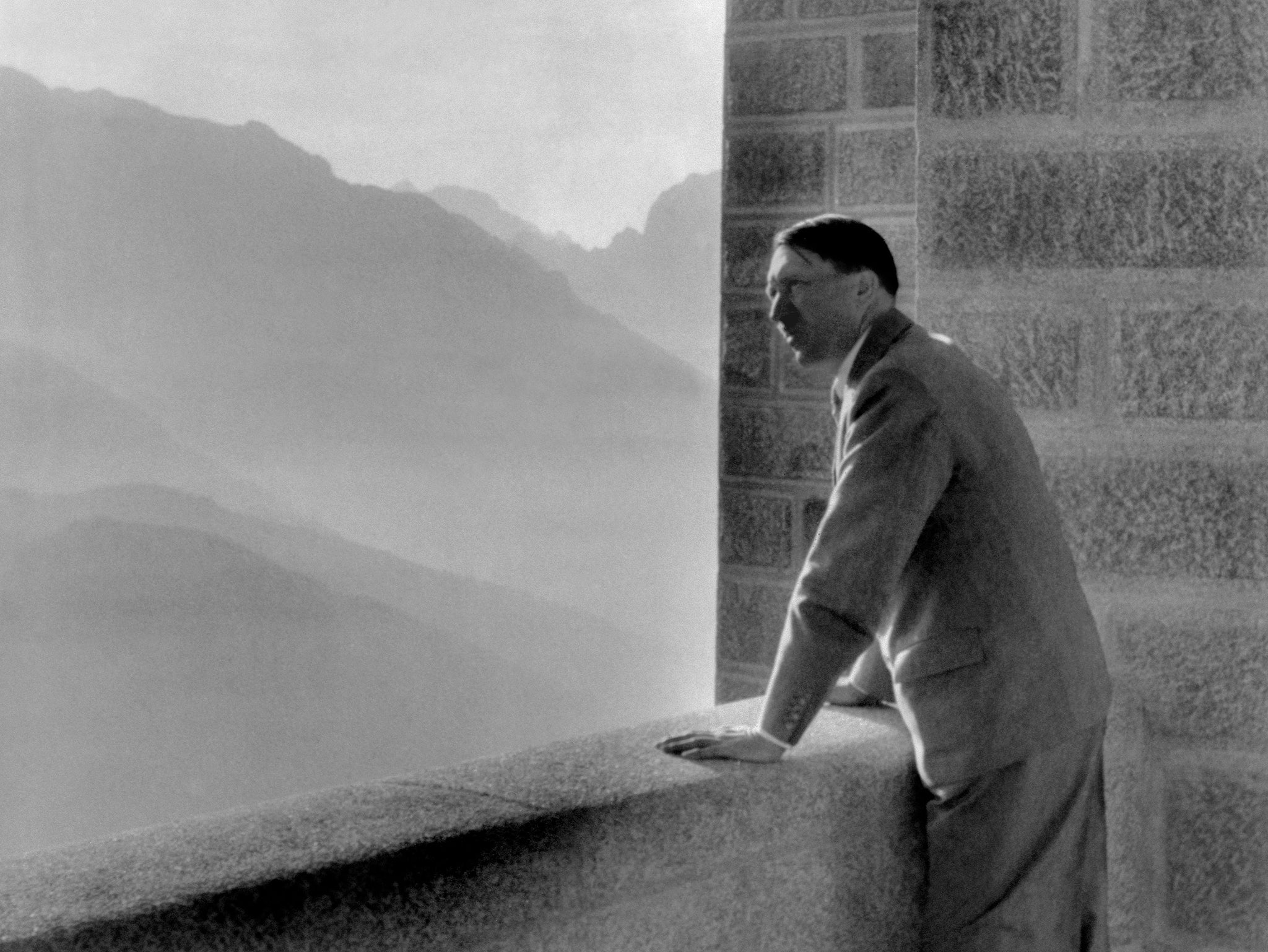

In The Boy at the Top of the Mountain we meet Pierrot, a half-French, half-German living in Paris in 1936. He loves his mother, respects his father and has a best friend in Anshel, a deaf Jewish boy from downstairs. When his parents die, he is sent away to an orphanage and then to live with his Aunt Beatrix, the housekeeper in a large property in the Bavarian mountains. But this is no mere lodge. Pierrot has been brought to the Berghof, Adolf Hitler’s home in the hills.

On arrival, Beatrix asks Pierrot to go by the name Peter and to forget about his French roots. He is never to contact Anshel again, and is to be grateful to the Führer for allowing him to build a new life in Germany. He is quickly won over by the charisma of his aunt’s employer, by the pageantry of the Hitler Youth, by the sense of his superiority that his father’s bloodline offers to him. It does not take him long to transform into a cold and callous teenager – in fact the process is almost uncomfortably speedy – and so easily swayed is Pierrot by the trappings of power that he conducts betrayal after betrayal, too smug to realise that his actions will have lasting repercussions on those he loves and on his own conscience.

Throughout, Boyne displays a satisfying grasp of life at the Berghof, weaving the fiction of Pierrot and his moral decline into real events. So we have a visit from the Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson, a cameo from iconic film-maker Leni Riefenstahl, scandalous whispers of Geli, Hitler’s niece, and displays of devotion to Blondi, his dog.

The blend is well-orchestrated, but there is the sense of a historical checklist, a feeling that Boyne has a list of researched points that he was intent on dropping in even when his own creations are far more involving. Aunt Beatrix, especially, proves to be far stronger, far braver than her initial introduction as a mere housekeeper suggests, while Ernst the chauffeur and Pierrot’s resolute classmate Katarina prove that the best characters aren’t always found in the history books. While Hitler treats his new ward like a Nazi mascot, these three attempt to guide Pierrot from the perils of the rising waves, even as they are threatened with destruction.

The Boy at the Top of the Mountain was perhaps given its title in the hope of riding its best-selling predecessor’s coat-tails, and if that’s true then there was no need for such lack of faith. True, there are plodding moments, and occasional examples of criminal predictability, but Boyne is at his best when examining guilt and culpability. As with The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, the ending absolves many of the flaws: the epilogue, a mere ten pages, culminates in a discovery so perfectly simple, and yet so unexpected, that it will remain with you for days. Isn’t that what you want in an ending?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments