The Bitter Taste of Victory: in the Ruins of the Reich by Lara Feigel, book review

A tale of hope quashed by the horror of war

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In summer 1949, Thomas Mann returned from California to make a bittersweet kind of royal progress through defeated, and now divided, Germany. In a Bayreuth hotel, the literary giant found that the last signatures in the guestbook belonged to Hitler, Himmler and Goebbels. Before adding his own name, he left 16 pages blank "for the 16 years of his exile". Smashed, broken, starving and demoralised, the bombed and wrecked Germany left by the Nazi downfall resembled a blank page, smeared in blood and strewn with rubble. Many survivors and observers read only despair in its ruins. To Stephen Spender, in flattened Cologne, "The sermons in the stones of Germany preach nihilism".

Yet, in the later 1940s, the victorious Allies sent writers, artists, actors and film-makers – both foreign stars and anti-Nazi émigrés – into this wasteland with a grandiose mission. They formed "the vanguard of the campaign to remake a country". Lara Feigel's vivid, crowded fresco of 20 figures who joined this cultural reconstruction – Marlene Dietrich to Jean-Paul Sartre, WH Auden to Lee Miller – recounts their brave, bizarre and sometimes futile endeavours.

In her justly praised debut, The Love-Charm of Bombs, Feigel braided five authors' lives in wartime London into a densely atmospheric tapestry of love, work, imagination and anguish under the shadow of the Blitz. Her second book repeats the method but expands the canvas. One of her London cast, the Austrian refugee Hilde Spiel, re-appears here along with her novelist husband, Peter de Mendelssohn, and a host of more familiar names.

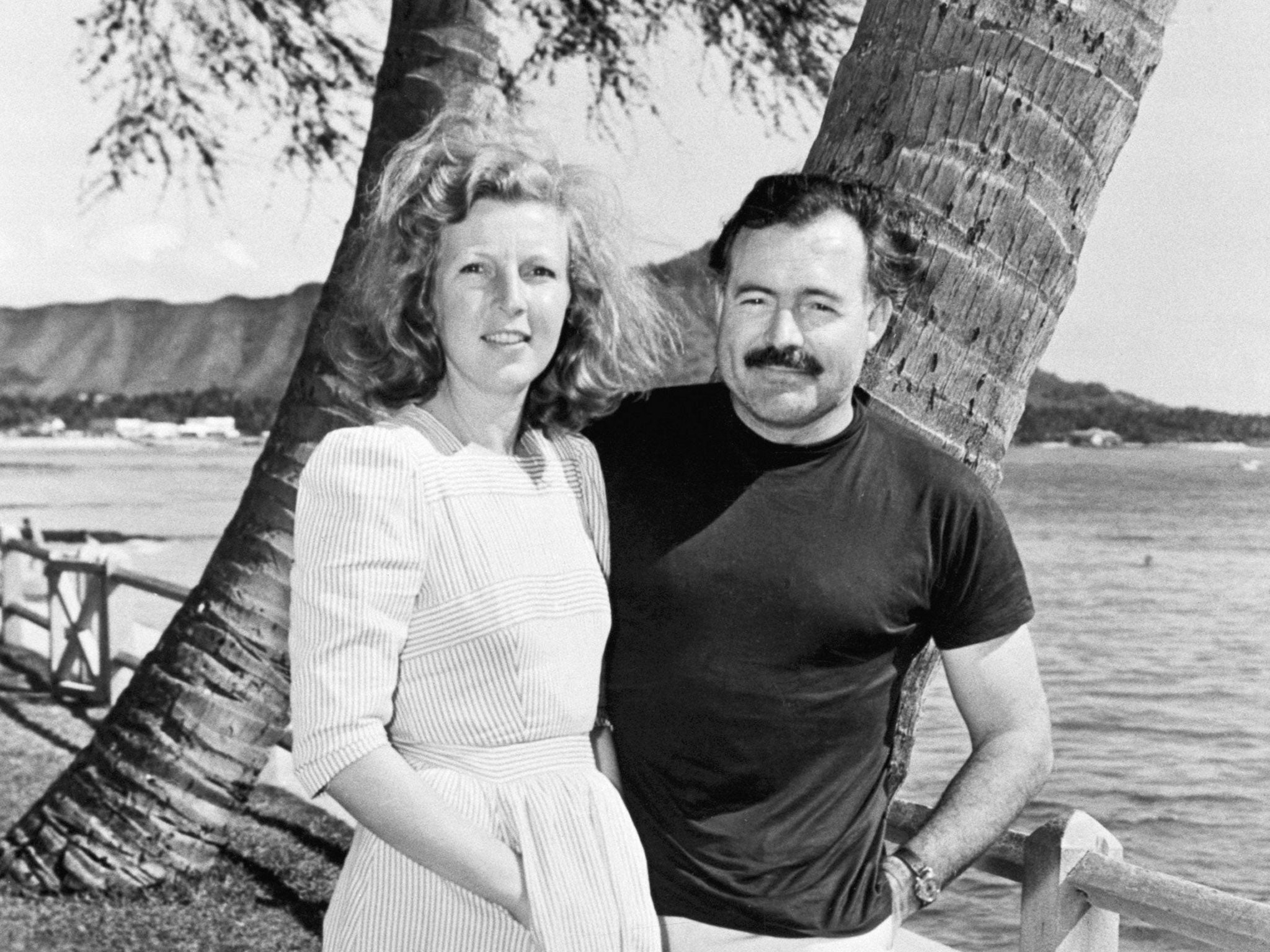

Not every witness has an equal role. At intervals, the family romance of Mann and his brilliant but tormented children, Erika and Klaus, threatens to hijack the entire narrative. But we begin with Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway, prickly rivals for front-line glory as war correspondents in late 1944, while their always-fragile marriage falls apart. As in her first book, Feigel entwines politics and passion, the wide screen of history and the close-up of desire among the ruins.

Typically, we view the Nuremberg trials largely through the eyes of novelist Rebecca West, who had an affair with chief American judge Francis Biddle. Extreme events, we see, can sharpen minds and quicken senses. In Nuremberg, West found "a climate where love can flourish". The dashing General James Gavin, commander of the US 82nd Airborne Division, enjoyed near-simultaneous affairs with Gellhorn and Dietrich: always an enlivening presence here. Talk about the spoils of victory.

Among the occupiers, idealists imagined a Germany reborn through artistic revival into a peaceful and democratic Kulturnation. Soon enough, the sheer desperation of survival amid the debris quashed many hopes. Besides, visiting artists often felt a grief and horror that doused any re-civilising zeal. After seeing the camp at Belsen, the actor Sybil Thorndike lamented that "I'll never get over today – never". For the philosopher Hannah Arendt, the legacy of Nazi tyranny and genocide merely brought "shame at being human".

As the nascent Cold War deepened rifts between Western and Soviet sectors, the dream of an arts-driven renewal faded. Culture "turned out to be decidedly secondary to Realpolitik". Still, Feigel's coda to this occasionally diffuse but always illuminating and richly textured panorama makes clear that short-term failure seeded long-term success. The post-1968 West Germany of dissent and ferment made good on many aspirations of the late 1940s, and blazed a trail towards re-unification. But what about Stephen Spender's yearning that a reformed Germany might anchor a harmonious Europe as "a transnational entity united by its common culture"? History's jury has yet to return its verdict.

Bloomsbury, £25. Order at £22 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments