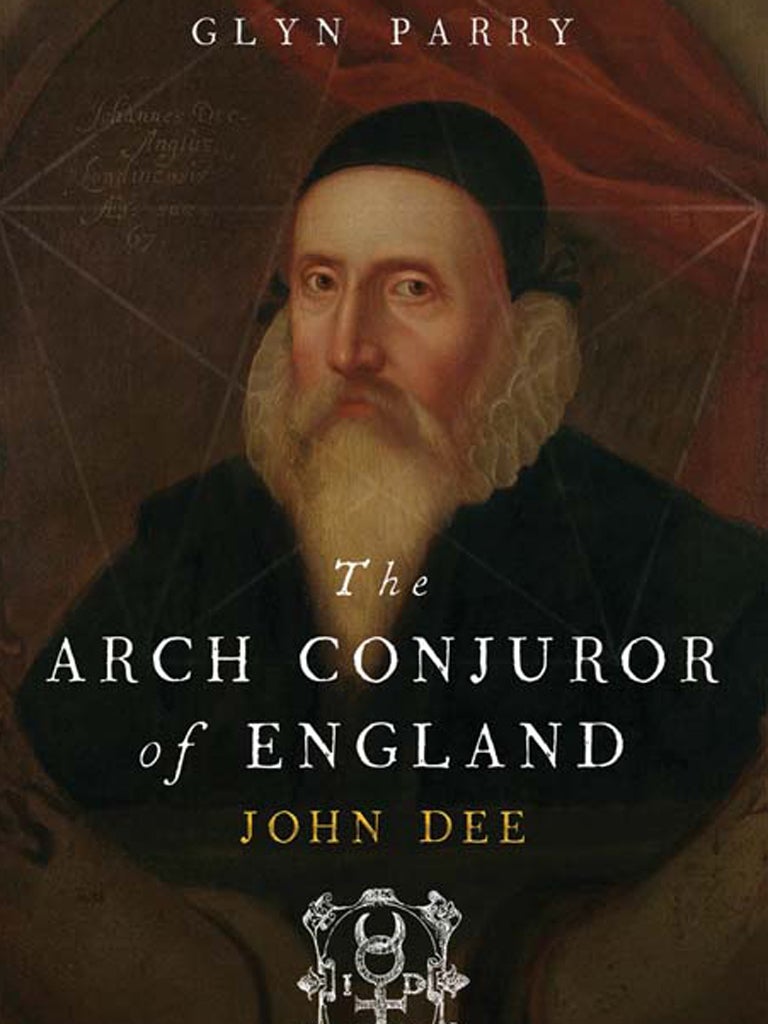

The Arch-Conjuror of England: John Dee, By Glyn Parry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Properly understood, the story of Dee's life opens a doorway into a forgotten Tudor landscape... a strange, unfamiliar place". So Glyn Parry begins his biography of John Dee, often thought of as Queen Elizabeth's astrologer. Parry is at his best in showing that Dee's fascination with astrology and alchemy was nothing unusual, but part of the intellectual milieu of the time. Dee was an occultist, but he was also a devout Christian: a Catholic priest before he was a Protestant one.

Along with many of his age, he thought these were the End Times, and the End would occur soon, probably in 1588. This fired his urgency for encouraging Elizabeth to "reclaim" her territories and become the Last World Empress. Dee is often credited with coining the term "British Empire". By this he meant his conviction that Elizabeth was descended from King Arthur, and so the rightful heir to all of his supposed territories.

Political and religious tensions were rife at court; plots abounded. Gossip and slander were deadly weapons. A forged defamatory letter referred to "doctor Dee the great conjuror". These attacks were published in most editions of John Foxe's anti-Catholic work Acts and Monuments, so the slanders were kept alive.

Dee was always short of cash. With his scryer Edward Kelley, he sought patronage in Poland and Bohemia. After six years, Kelley claimed to have found the secret of making gold and was suddenly lauded; Dee, unwanted, returned to England without him in 1589. There he found his protectors and patrons had died, and public opinion had turned against the practice of magic.

Elizabeth's court was a battleground between anti-Catholics, anti-Presbyterians, and those who tried to steer a middle way. Parry's focus in this biography is on setting Dee's life firmly within this perpetual in-fighting. The book is a thorough piece of research, and a worthwhile scholarly work. But a historian also needs to make his subject's life come alive, and this is where the book falls down. Dee is blown between competing courtiers, but Parry seems more concerned with the intricate political connections than with the man caught in the middle of them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments