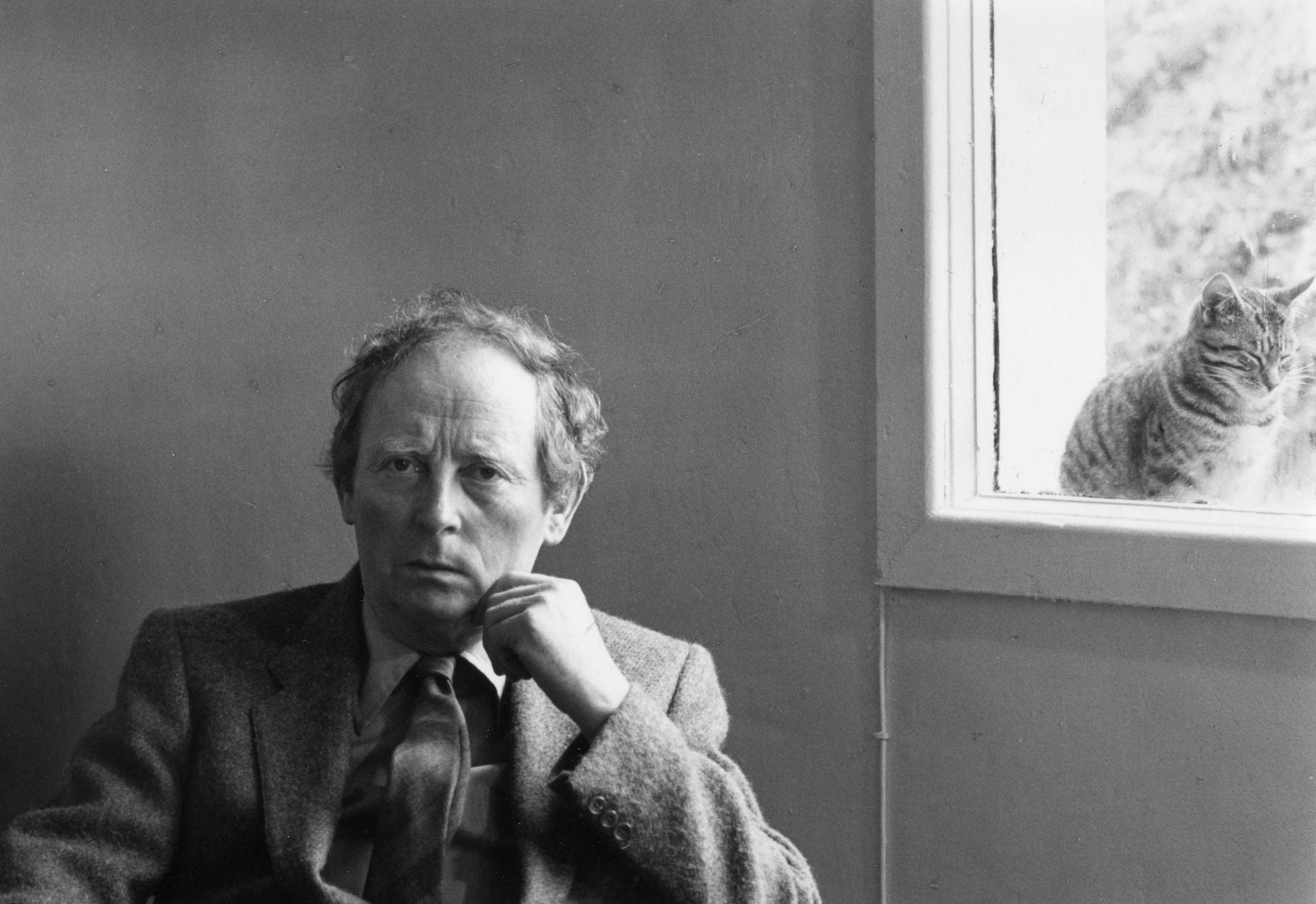

That They May Face The Rising Sun by John McGahern, book of a lifetime

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I meant to read John McGahern's That They May Face the Rising Sun ages ago but books have a way of finding their moment. I was on holiday, not far from where the novel is set in McGahern's native Leitrim, when I came across a copy in our cottage.

I was in the right place and I could read at the right pace, with calm concentration, in the peace of the garden. Soon the novel took over. When we drove off to nearby Carrick or to the beach at Sligo, I was living and breathing it. In the evenings I read passages out to my husband for the sheer beauty of them. When I finished the book, I felt both satisfied and bereft.

Joe and Kate Ruttledge go back to Ireland from London, giving up their professional jobs, to live on a small farm. They are not tourists turned experimenters, fantasising about the good life; they know the limitations of a close-knit rural community. They remain outsiders of sorts and yet they find their place. Most of the novel is conversation between neighbours. It quietly observes the rituals and dramas of their lives, moving to the rhythms of work on the land, the seasons of birth, marriage and death. There is violence and kindness, bigotry and tolerance, but the reader is left free to judge or to forgive.

Since I've been married to a man whose parents came from Cork and County Mayo, I've realised how ignorant I am of Ireland, despite my reading. McGahern's great novel made me slow down, see more, and listen harder to the people we met. The book could only be Irish but like the Ruttledges' house, it stands with its doors open, inviting you over the threshold. "The universal is the local," McGahern once wrote, "but with the walls taken away."

So much modern fiction makes exile the precondition for becoming an individual and an artist. But some of us know how much was lost when we left home and went away to college. McGahern conjures the warmth and decency of working people without sentimentality. He gives them dignity, while keeping his distance. Ultimately he celebrates those who are well off in the best sense because they are glad to be alive. While I have been writing my own family history, I have tried to keep McGahern's humanity in mind.

Alison Light's book, 'Common People' (Fig Tree), is shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize for non-fiction 2014

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments