Swansong 1945, by Walter Kempowski, book review: History retold, word by word

German historian and novelist Kempowski gathered more than 400 distinct voices to bring just four significant days to life: from Hitler’s final birthday to the day of the German surrender

It’s hard to know what metaphor to use for Walter Kempowski’s Swansong 1945, but it isn’t easy to describe without one.

The book tells the story of the final days of the Second World War through quotation fragments that are assembled to form – what – a patchwork, a chorus, a jigsaw, a mosaic?

German historian and novelist Kempowski gathered more than 400 distinct voices (with Shaun Whiteside here taking on the translation of all of them) to bring just four significant days to life: the first, Hitler’s final birthday, 20 April; the last, the day of the German surrender, 8 May, VE Day. Whatever it is, this form, it’s immensely effective.

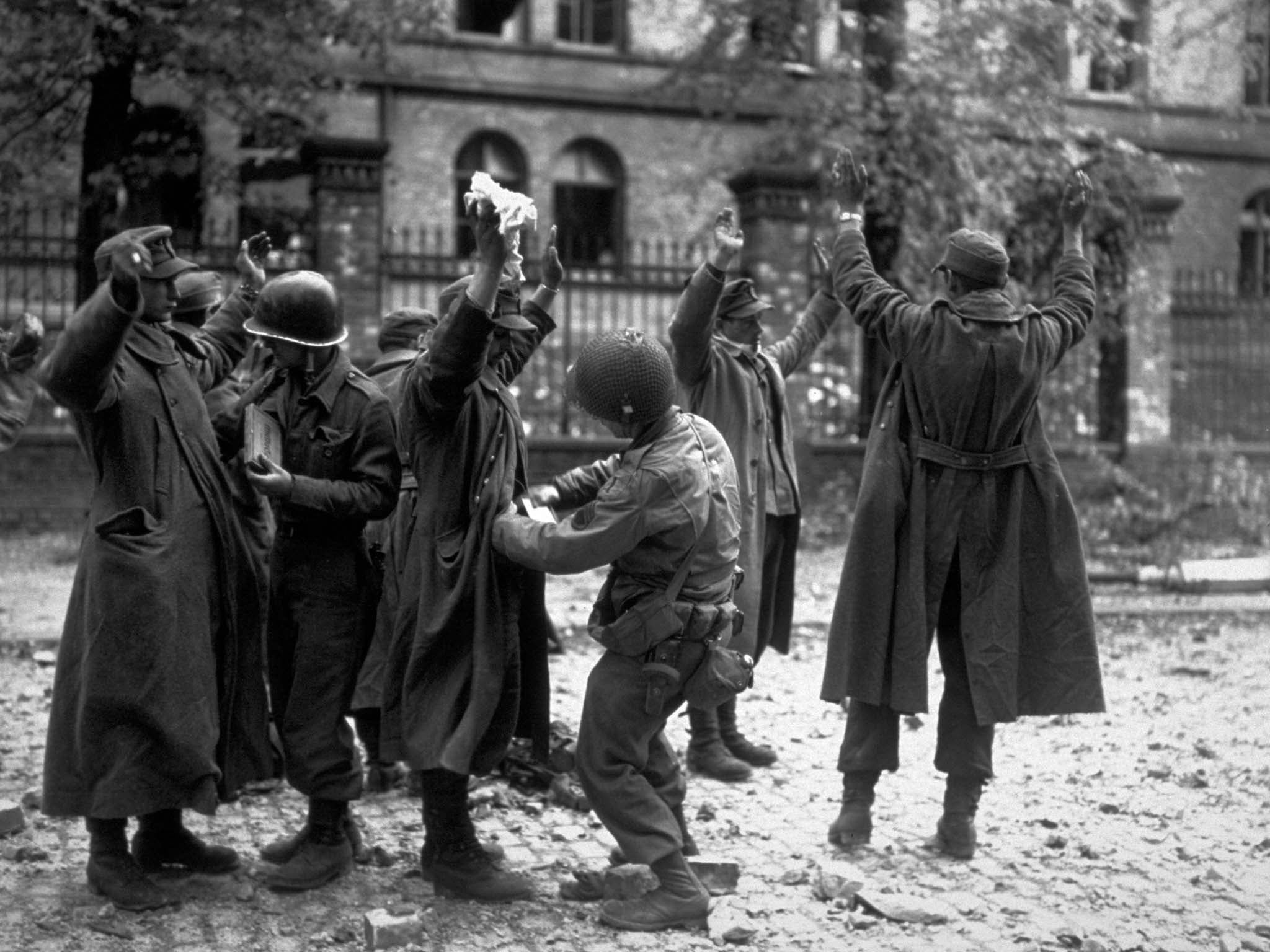

Many, but not all, of the voices are German – some deeply entangled in the machinations of the Reich (soldiers of every rank, a telephonist in Hitler’s bunker, or Hitler himself), others are involved only collaterally: a postal official, a teenaged seminarian, a nameless woman queuing for water at the city pump. Ordinary people speak alongside heads of state; military men alongside poets; bystanders and perpetrators and victims.

Each little extract is a revelation – as often as not, what’s revealed is something domestic, even banal, but it feels like a revelation nonetheless. While some are deliberately crafted pieces of prose (the transcripts of formal speeches, or the carefully turned words of great writers), many more are artless (the letters, recollections, or diaries of ordinary people), and no less potent or evocative for that. But, of course, it’s their cumulative effect that makes the book so remarkable, because even if the quoted extracts are not all artful, their selection and meticulously considered arrangement certainly is. One extract gives you a glimpse of some new part of the picture, then the next confirms it, or challenges it, or chips slightly away at its edges. A radio address by arch-propagandist Joseph Goebbels (“We will be friends once more with all people of good will …”) is followed by responses from his unconvinced listeners. Grand statements commemorating victory are tempered by everyday realities. “A thunderstorm greeted VE Day,” writes a worker in a Somerset nursing home, “but was over before I went to join the longest fish queue I remember.” Soon what had first seemed an unwieldy pile of individual glinting pieces is revealed to be intricate with connections, with insight, and the significance of real lives.

The best history writing doesn’t simplify a reader’s understanding of the past, it complicates it. It adds layers, draws out contradictions and sharpens them, digs down into complexity, presenting a narrative that is rich and not simple at all. Swansong 1945 does all these things supremely well.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments