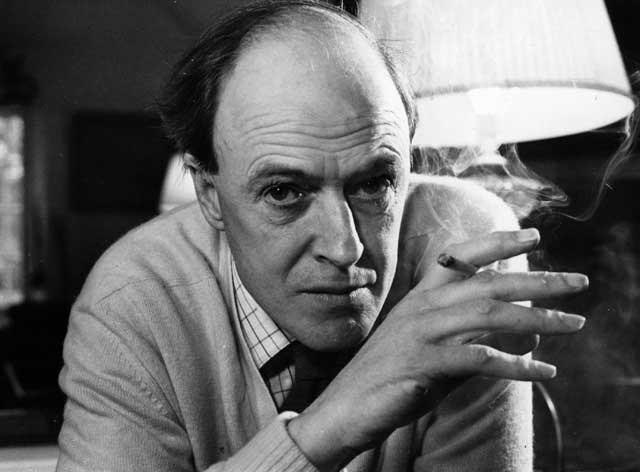

Storyteller: The Life Of Roald Dahl, By Donald Sturrock

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A mere 16 years ago, Jeremy Treglown wrote a well-reviewed biography of Roald Dahl. Yet Dahl's daughter Ophelia asked Donald Sturrock to do the job again – fulfilling a task her father had assigned her: to write his life story or appoint someone else. In a 2002 interview, Ophelia said Treglown's book portrayed her father as "a difficult, demanding, unpleasant old bugger... it didn't show his funny, kind side." This time the family, which granted access to letters and papers, also did not interfere. They asked only that Sturrock conveyed the man that he knew and liked. He has succeeded.

Sturrock first met Dahl in 1986, while making a BBC documentary. Despite Dahl's first response - "they've sent a fucking child" - Sturrock became a friend and recurrent visitor to the Dahl family home in Great Missenden. Sturrock cottoned on to the fact that his vastly entertaining host was not always truthful. Dahl pretended, for instance, that the ordinary kitchen knife he was using was a precious legacy from his father; and Sturrock never established the veracity of Dahl's claim that he had lunched with Stravinsky.

Hence the title of this book: Dahl wrote stories, but also reinvented his own history. Disentangling the truth even from Dahl's own memoirs, Boy and Going Solo, was aided by letters unavailable to the first, unofficial biographer.

Sturrock's achievement is to have produced a "warts and all" portrait of Dahl, which does not shrink from the actions, utterances and character traits his detractors would cite, but still allows us to understand why people were charmed by Dahl, why he was so spectacularly successful as a bedder of women, how he became a friend of movie stars, millionaires, statesmen and distinguished writers – in short, why he was loved.

This is no hagiography - it is possible to read this biography and dislike Dahl; even Sturrock has admitted that he liked him less after he wrote it. But to show Dahl's clay feet alone would hardly be a comprehensive portrait of all six-foot-six of the man.

If Dahl was difficult, there are plenty of circumstances that might have made him so. Born to Norwegian parents, growing up in Wales, he was always an outsider. When he was three, his seven-year-old sister, Astri, died from peritonitis after a burst appendix. Shortly afterwards, his grief-stricken father succumbed to pneumonia and died.

The family was obliged to swap their rambling, idyllic farm for a suburban villa. Although treated by his mother with "suffocating adoration", he was taken to have his adenoids out without anaesthetic, and sent away at seven to a prep school where life was a homesick round of canings and cruelty, exceeded only at his secondary school, Repton. Working for Shell in East Africa he endured malaria and jungle hardships. When war broke out and he became an RAF pilot, he was one of only two of his squadron who survived, sustained lifelong injuries when he crashed into the desert, and learnt what it was to kill. All this in his formative years.

Adulthood brought catastrophic head injuries in a traffic accident to his son Theo in babyhood; the death of his seven-year-old daughter Olivia from encephalitis (after measles); cerebral haemorrhages that disabled his wife, the Hollywood actor Patricia Neal, aged 39; the sudden death, from an aneurysm, of his stepdaughter Lorina at 26.

This more-than-fair share of tragedies also contrast with some exceptional good fortune, attributable to talent and charisma. Dahl's first short stories met immediate success. A story about Gremlins won him a friendship with Walt Disney and a commission from Roosevelt's vice-president, Henry Wallace.

As a handsome flying ace employed by the RAF in Washington, and by the shadier intelligence outfit the British Security Coordination, he was feted in the grandest circles. He dined with Ginger Rogers, befriended Howard Hawks, stayed with Hoagy Carmichael, acquired a rich patron, Charles Marsh, and slept with Martha Gellhorn (while she was still married to Ernest Hemingway) as well as with a good many other older, glamorous, wealthy women. It makes for an eventful book.

Sturrock shows with vivid examples that Dahl was unfaithful, provocative and sometimes cruel, but the promiscuous and opinionated are interesting to read about if not comfortable to live with. He was not always sensitive: he failed to appreciate how unhappy his daughter Lucy was at school until she set fire to it. But we learn that he could be loving (especially to his second wife, Felicity), entertaining and generous.

In adversity he was practical, resilient and inventive. When Pat was ill, he subjected her to a rigorous regime which enabled her to return to the stage in an astonishingly short time. It seemed harsh, but was just what was needed. When Theo was injured, Dahl found a toymaker who constructed a new valve to his own design that did not fail, and went on to be used on 3,000 children. It even saved the life of his agent's son.

Sturrock provides the bigger picture, from Norwegian fishing villages to British public schools. He also offers telling details – that, for instance, while his mother kept all Roald's letters, he burnt hers; that Dahl preferred to make love in the dark; that he had all his teeth out in his twenties; and that he served bars of chocolate to dinner guests from a red plastic box (a more acceptable indulgence when you don't have your own teeth).

Sturrock is restrained about analysing Dahl's psychology, but his evidence makes it unsurprising that Dahl found his metier regressing to the age of seven in his writing hut. What is most astonishing is not that there was a dark strain in Dahl's writing, both in the early, macabre short stories for adults, and the children's stories he produced in later life, but that out of all the misery came humour and lightness, both in the life and the work.

Sturrock gives a compelling account, and makes good use of Dahl's own voice. It makes you want to revisit the prose of the storyteller himself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments