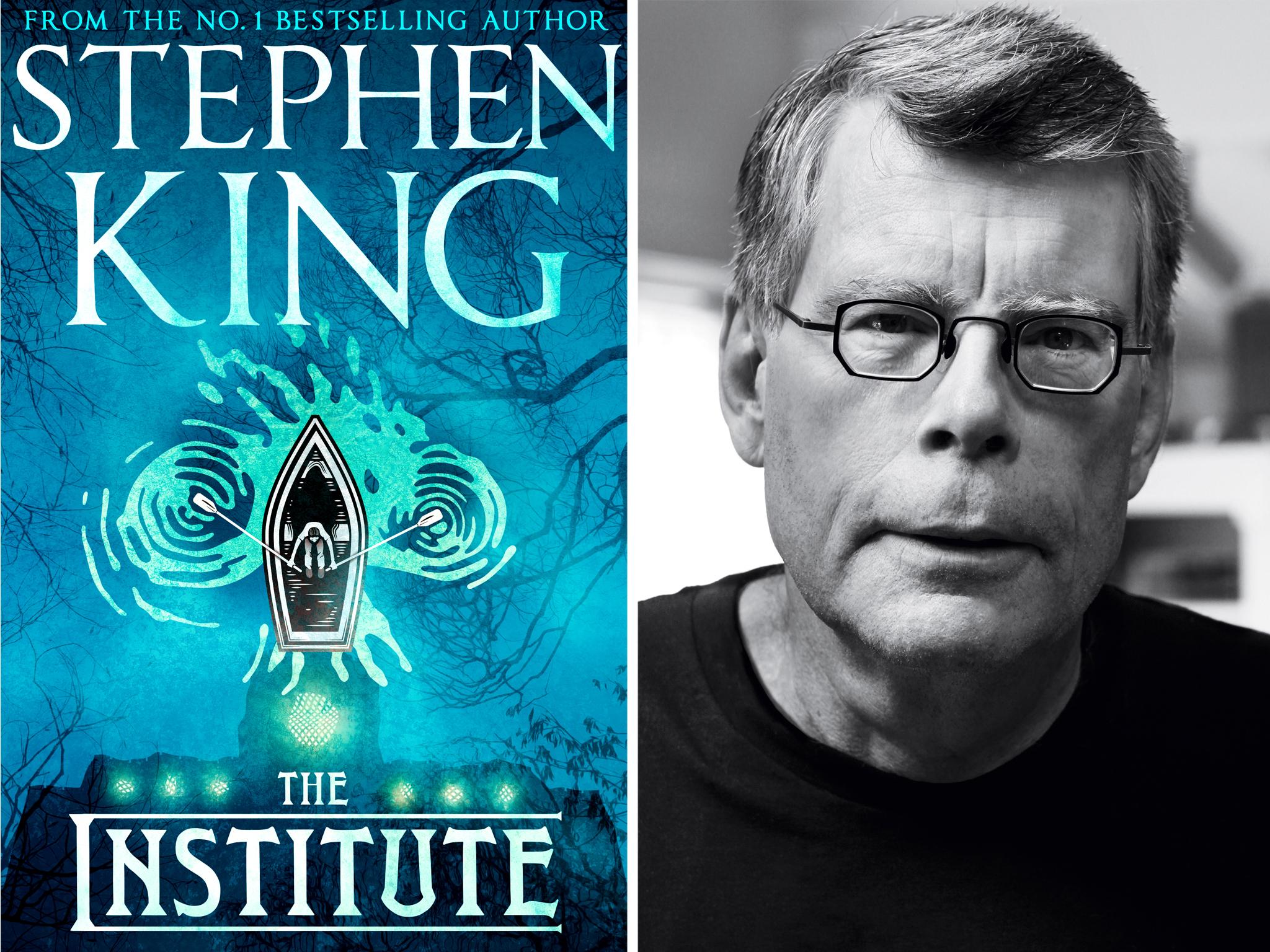

Stephen King’s The Institute, review: Crackles with delicious unease

King’s new book might remind you of Netflix’s ‘Stranger Things’, but he has been writing about psychic children and conspiracies since the Sixties

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s no question about it: Stephen King is a past master at casting an eerie shade on familiar fictional materials. His new book, The Institute, concerns a sinister government facility, operational since the Second World War. Hidden in the depths of the American forest, the organisation known as “the Institute” sends out special forces to kidnap children (having first dispatched their families), and subjects them to all kinds of horrific tests in order to bring out their developing psychic powers.

If you are now thinking of the recent Netflix show Stranger Things, don’t forget that King got there first: he’s been writing about psychic children and conspiracies since the Sixties. There’s even a sense here that he’s having fun. Among the youngsters in the Institute are a pair of girl twins, which are reminiscent of the characters of “some old horror movie”.

King is supreme at crafting the building blocks of a story and laying them together in a slick, teasing and apparently simple way. But there is also a wealth of political references: libraries not getting enough cash; the military-industrial complex and some of its dodgier moments such as waterboarding; as well as the Trump administration (at which there are many digs, some sly, some less so).

We begin with Tim, an all-American hero loner ex-cop – a type, to be sure, but given depth, thoughtfulness and a quick intelligence that sets him apart. He’s lost his job thanks to a freak occurrence, which turns out to be one of the major themes: is an event the result of pure chance, or is it somehow destined? The bulk of the story, however, takes place in the dirty, grey, sinister Institute itself, and from the perspective of 12-year-old Luke Ellis.

Supremely bright, Luke was on his way to matriculating at two universities at once. He learns, and needs to learn, in order to keep his distance from a terrifying abyss he can sense inside him. This is one of the many destabilising images that King sneaks in, catching you off-guard. If there is a fault here, it’s that this dizzying sense of encroaching chaos isn’t fully explored.

Soon Luke is snatched away by the goons of the Institute. King preys on deep fears: Luke wakes up in a place that’s been decked out exactly like his bedroom at home, only without a window. That is a powerful childhood terror: to wake up somewhere familiar, and for it to be somewhere utterly other, the domestic rendered alien. Here, Luke finds several children in the same predicament. They are told they are heroes, helping to save the world; but they are tortured until they burn out.

The Institute isn’t overly violent or shlocky, as some of King’s books can tend to be. In many ways, especially with Luke as its protagonist, it could almost be young adult fiction, particularly as it relies on the idea that children, when connected, are a powerful insurrectionary force. Nevertheless, there are deeply sinister scenes, such as one in the incinerating room, made even more creepy by the fact that a staff member likes to meditate there. Auschwitz is mentioned, and Luke makes comparisons between the staff, who blindly imagine they are doing the right thing, and those who went along with the Nazi regime.

Everything you would expect from King is here: eccentric background characters (the tramp who believes in government conspiracies, the 70-year-old secretary who’s also handy with a gun, the doctor who’s slowly going crazy thanks to over-exposure to telepaths); a sturdy, controlled plot; and a sense of the kind of bonkers, slant-wise imagination that gave us It and Pet Sematary. While not his best, The Institute still hums and crackles with delicious unease.

Stephen King’s ‘The Institute’ is published by Hodder & Stoughton on 10 September, £10; Philip Womack’s latest novel, ‘The Arrow of Apollo’, will be published in May 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments