Romain Gary: A Tall Story, By David Bellos

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Over a 35-year writing career, Romain Gary published 21 novels and six memoirs in two languages under half a dozen names. Lionised in 1945 for European Education, a vivid account of the wartime Polish maquis, he was snubbed by the Parisian literary establishment which dismissed The Roots of Heaven, winner of the 1956 Prix Goncourt, as a commercial sell-out. For the next decade he wrote in English before returning as "Emile Ajar", author of La Vie devant soi (Life Before Us). Both a critical and popular success (it won the 1975 Prix Goncourt), it sold more copies than any previous French novel. When comparisons were made, critics declared Ajar a far better writer than Gary. The truth did not emerge until after Gary's death. It did little to sweeten obituaries penned by critics left with egg on their faces.

Roman Kacew, born to Jewish parents in Russian Vilna in May 1914, grew up in Polish Vilnius between 1919 and 1928, by which time he was fluent in Russian, Polish, Yiddish and German. In that year, he and his divorced mother migrated to Nice, where he acquired another culture and added another language. His belief system was unstructured and intuitive. He never went near a synagogue, was an occasional Catholic, never joined a political party and remained wedded to the values of 19th-century humanist fiction. Most of him felt French but cosmopolitanism was his destiny. It meant, as David Bellos argues in this alert, riveting, wonderfully fluent biography, the first in English, that he always had problems with identity.

After graduating in law in 1938, he enlisted. When France fell in 1940, he fled to Britain and saw active service in Africa, Egypt, Syria, and Europe as a flying officer in the Free French Air Force. He was twice wounded and wrote his first, "Polish" novel on his knee, between sorties. He admired de Gaulle whom he thought symbolised not only "a certain idea of France" but a noble, honourable concept of service to right causes, winnable or not.

His war record opened the door to a diplomatic career which took him to Bulgaria in 1947, where he saw through the great Stalinist sham long before the comrades of existentialist St Germain-des-Prés. Out of step with post-war literary fashions, he failed to capitalise on the success of his first novel but made up for it with success and a spangled private life.

He was a fastidious dresser, drank little, ate simply but was a sexual glutton. He had fewer women than Simenon (who laid claim to 10,000) but remained addicted to casual encounters into his sixties. He was attractive to women (though his first wife, the writer Lesley Blanch, thought he looked like a stern icon) but had a short fuse with men: he once challenged Clint Eastwood to a fist fight.

Journalism and the film of The Roots of Heaven (1958) made him rich. It was as a celebrity in his own right that his diplomatic career took him to Los Angeles as Consul Général in 1958. He took his duties seriously but found time to write novels in different inks. Bellos identifies several types including a libertarian "Nazi cycle", a series of unpreachy moral fables featuring secular saints (like Morel of The Roots of Heaven who dies in an unwinnable but honourable campaign to save the African elephant from hunters) and uproarious satires. Gary's targets included the United Nations, where he worked, and American celebrity culture. His jokes could be very good: "We'll get out of here," says one character, "and live somewhere in Hollywood, far from civilisation."

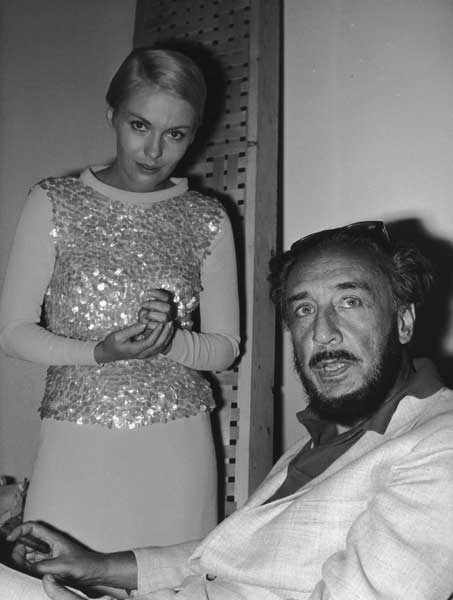

Bellos is a sympathetic guide to Gary's unsettled life, and nowhere more so than in his treatment of his second marriage in 1963 to Jean Seberg. Gary behaved impeccably as Seberg, thrust into stardom as Saint Joan by Otto Preminger, slowly descended into instability. Yet there are plenty of warts on view. Bellos calls Gary a liar, spoiled brat, a boor and an oaf. Nor is he an unconditional admirer of his work. He derides Gary's ventures into theatre and cinema, calls The Roots of Heaven "a middle-brow page-turner" and Pour Sganarelle, Gary's essay on the art of fiction, a "rag-bag of opinionated bunkum". Yet he makes a sound case for Gary as a brilliant storyteller, a master craftsman and one of France's most original writers.

Gary is an unlikely hero of modern times, with a distinctly old-fashioned world-view. He himself was a victim of war and prejudice. But he mistrusted all victims because they can so easily turn into victimisers. For him, tolerance did not mean special treatment for the downtrodden. It meant giving Blacks, Jews, left and right, any group or sect, the right to behave as badly as everyone else. The process is slow and mistakes are made . Yet humanity is "a work in progress".

So was Gary. Living on the human margin, he was tempted to flee from himself (and civilisation). As a novelist, he could imagine better worlds and become someone else. In the end, fatigue and the fading of his sexuality robbed even fiction of its ability to offer renewable incarnations. Romain Gary, questioning the logic which lets us tolerate abortion but not euthanasia, finally stopped trying and shot himself in December 1980.

David Coward's recent translations include Hedi Kaddour's 'Waltenberg' and Paul Morand's 'Hecate and her Dogs'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments