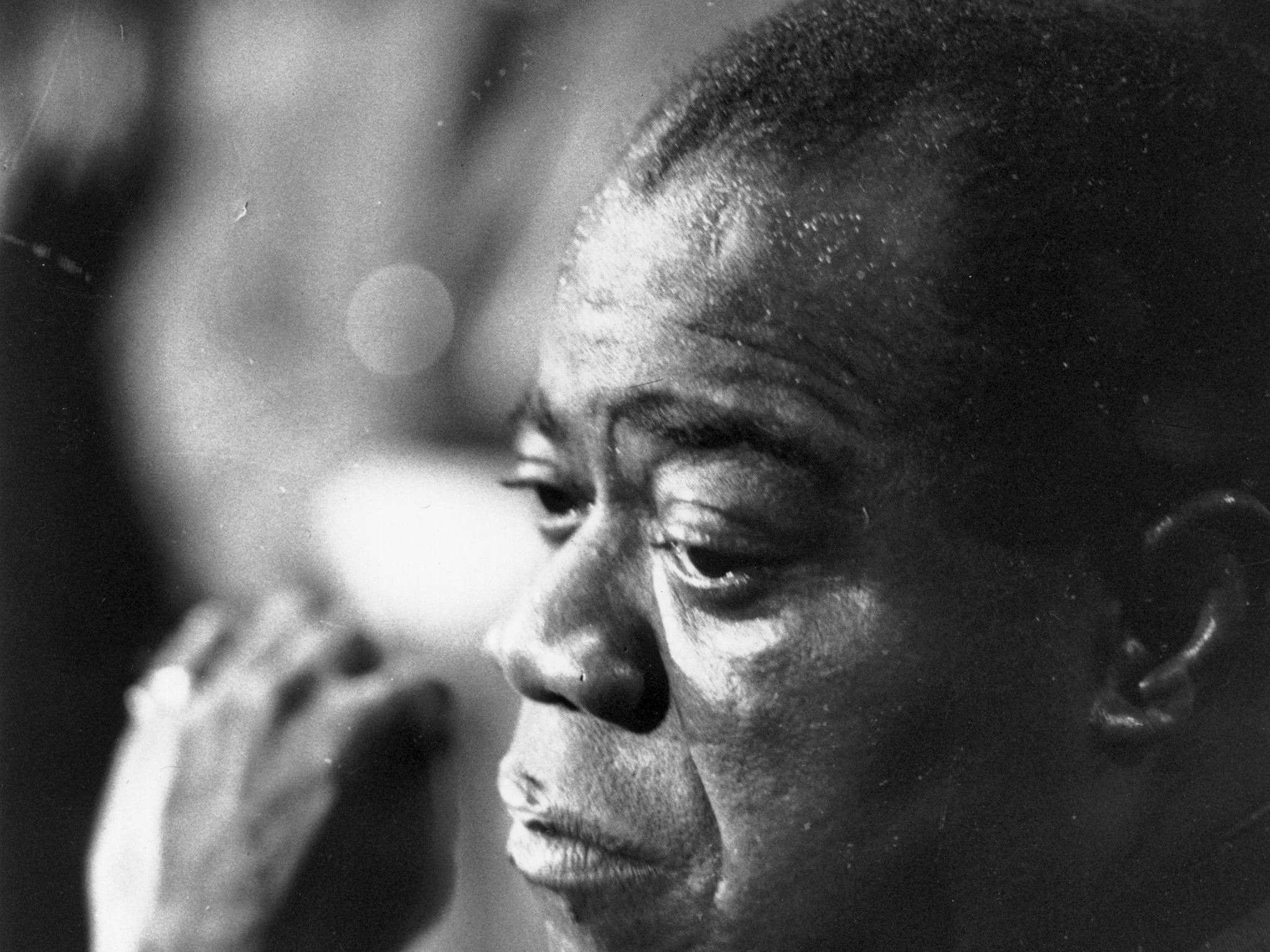

Paperback reviews: Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism by Thomas brothers, Ada Lovelace, bride of science by Benjamin Woolley

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism by Thomas brothers

Norton £12.50

Brothers’ contention, in this scholarly but accessible biography, is that while the early influence on Armstrong’s music was the streets of New Orleans (“all about the intensity and directness of blues-based sensitivity on the one hand, and a brash aggressive street posture on the other”), what actually made him modern was the African legacy. Improvisation, “a strong percussive attack” and non-notated music all find their antecedents in African music, he argues, a “fixed and variable model” that was then carried to the States by slaves.

It’s worth remembering how close Armstrong’s rise was to the end of slavery in the US: when he reached a professional high in the 1930s, playing with his own orchestra all over the States, his success was only 70 years away from the Civil War, about what we are from him now. Brothers’ thesis never forgets that recent history, as he explored the need for a new black identity still waiting to emerge from that experience of slavery. It was Armstrong who answered that need through his music.

Innovators are often troubled people. Brothers isn’t so concerned with Armstrong’s private life in this largely music-focused account, though we see glimpses: the difficult boy sent to a juvenile delinquent home aged 11, the three marriages, the arrest for marijuana possession. But, like many who made their way in the new entertainment industry of jazz and talking pictures, his work ethic was second-to-none. Musical genius and boundless energy made for an individual whom Brothers compares to Mozart and Schubert. If later success made him appear a kind of Uncle Tom figure, pandering to white audiences in ill-chosen movies, it should not undermine the impact of his earlier work. Armstrong’s music was recognisable to many but it was also subversive: we forget the importance of the latter at our peril, warns his biographer.

****

The Good Son by Paul McVeigh

Salt £8.99

From The Go-Between to Atonement and a great deal in between, the figure of the betraying child, the innocent who sees too much of an adult world and ultimately punishes that world for the loss of his or her innocence, has become a cliché through sheer over-representation. All credit then, to McVeigh, who, in his debut novel about a boy growing up in Belfast during the worst period of the Troubles, has done an excellent job of breathing new life into it.

Mickey Donnelly is necessarily appealing: a boy who adores popular culture, his dog, his little sister Wee Maggie, and his mother, though not always in that order. His life is a series of negotiations past the mix of extreme and minor acts of violence and trouble represented by his alcoholic father, his older brother Paddy, the big girls at school, British soldiers, and anything else that stops a small boy having fun. There’s the inevitable tug at the heart-strings, an appeal to sentimentality that McVeigh might have avoided, but ultimately this is a highly commendable debut, convincing in its realism.

***

Ada Lovelace, bride of science by Benjamin Woolley

Pan MacMillan £9.99

Ada’s mother, Anne Isabella Milbanke, who had the misfortune to marry Byron, is rarely given an easy ride by biographers. They tend never to forgive her for propagating the story of Byron’s relationship with his sister, which in turn led to his exile and early death. Woolley doesn’t differ from this attitude, and it’s used to great effect to create sympathy for Byron’s daughter, Ada, pictured at the mercy of a cold and bitter mother. Ada herself is a fascinating figure, whose interest in science led to work with Babbage and the invention of computer programming. That her parents’ history is given as much attention as her achievements is simple human curiosity, but Ada may prove in time to be more important than either of them.

***

Out of Winter by Carol Lee

Hodder £8.99

Lee’s account of finding herself suddenly having to care for her elderly parents might not seem immediately appealing. But this is an honest, heart-felt and compelling memoir that will resonate with many. Lee’s father, a former RAF pilot, is admitted to hospital suffering from dehydration. From there it only gets worse as Lee discovers her mother’s short-term memory is seriously impaired, they can barely look after themselves, and won’t countenance a home or sheltered housing. Lee finds herself increasingly reliant on the kindness of neighbours, friends, and extended family. She speaks for a generation of women in particular, to whom the responsibility of caring for elderly parents generally falls.

***

The Giraffe’s Neck by Judith Schalansky

Bloomsbury £8.99

The quirkiness of Schalansky’s tale of German schoolteacher Inge Lohmark enhances its more disturbing and occasional darkly humorous aspects. Lohmark is a teacher of biology and adheres to a Darwinian philosophy of survival of the fittest, alas for her pupils, who usually find that they are hopelessly unfit. But the real tragedy is that she applies such principles to her relationship with her adult daughter, Claudia, whom she rarely sees now. We find out about a childhood incident that changed everything between them, but it’s the change in school funding that really threatens her identity as she must adapt to survive. Schalansky’s prose contains just enough personal insights to prevent Lohmark from becoming a monster.

***

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments