Paperback reviews: Extreme Metaphors, The Defections, Daily Rituals, The Memory Palace: A Book of Lost Interiors, Critical Mass

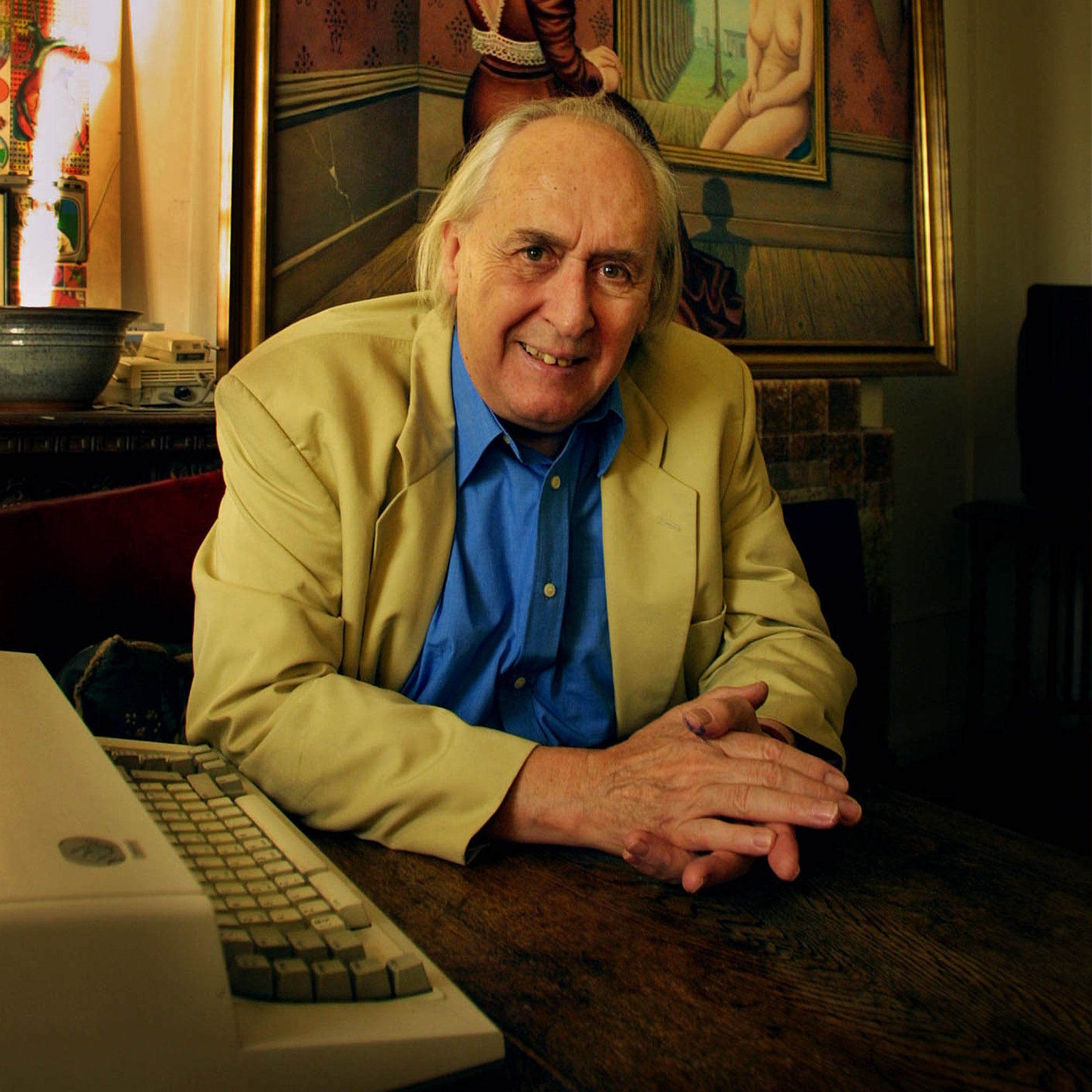

The lasting impression is of Ballard (above) as a wry magician, revealing his methods without ever ruining the trick

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Extreme Metaphors edited by Simon Sellars and Dan O’Hara (4th estate £10.99)

The allure of J G Ballard’s fiction lies partly in his willingness to foreground his obsessions. He’ll often have a character elaborate a novel’s central theme: in Millennium People, for instance, the louche physician Richard Gould seems to act as a mouthpiece for the author himself, talking at length about how the middle classes bury their lust for violence beneath social codes. In the hands of a lesser writer, such an approach would appear didactic, but Ballard usually gets away with it, such is the clarity of his thought and the elegance of his prose.

The many published interviews with Ballard, collected in this well-edited volume, are interesting for a similar reason. From the early 1960s to the late 2000s, Ballard would entertain fellow writers and journalists at his suburban semi in Shepperton and answer their questions. He would show a more playful side of himself than is sometimes evident in his stories, coining provocative aphorisms: “The idea of America is dead,” he told Lynn Barber in 1970, “because America was built on the assumption that tomorrow is a better day.”

What’s really fascinating here, though, is that uncanny ability Ballard has to explain his work without reducing it. There’s nary a hint of posturing or evasiveness in all the 500 pages of this book. He readily agrees with the philosopher John Gray that Super-Cannes “is really about” consumerism as a form of “social control”; and tells Will Self that Rushing to Paradise is essentially a study of the “fanatical personality”. Somehow such statements both illuminate the novels in question, and leave their deeper mysteries intact. The lasting impression is of Ballard as a wry magician, revealing his methods without ever ruining the trick.

****

The Defections by Hannah Michell (Quercus £7.99)

At the centre of Hannah Michell’s excellent debut novel is Mia, a translator at the British Embassy in Seoul. Half-English, half-Korean, she feels like an outsider both at work and at home. She strikes up a friendship with Thomas, a married diplomat with a drinking problem, and they start an affair. But when Thomas is tasked with investigating Mia’s apparent links to North Korean defectors, he begins to question the wisdom of the relationship. Written in crisp prose, Michell’s novel deftly weaves the tale of Mia’s torrid romance with the political history of the Korean peninsula. But in many ways her presentation of the British expatriates is more intriguing: like the embittered colonials in the stories of Graham Greene, Michell’s Brits are both arrogant and insecure. However, Michell’s new Orientalists find that globalisation has drained the East of its exoticism: “Everything about [Thomas’s] new posting seemed familiar. The skyscrapers, the shops, the traffic. Another Asian city. Where was the Orient?”

****

Daily Rituals by Mason Currey (Picador £8.99)

Mason Currey’s book explores how great writers and artists organised their lives and routines. Many of his subjects struggled with deadening day-jobs and needed to find spare hours to complete their true work: Franz Kafka, who toiled as an insurance officer, described the need to “wriggle through” the competing demands on his time. For others, it was more a matter of organising their days to facilitate productivity: Hemingway would always stop himself in full creative flow, so as to ensure he knew where to pick up the next day; Woody Allen heads out for a walk before settling down at his desk to pen a script. Currey is an excellent writer himself, and each entry can be read as an entertaining and witty capsule biography.

***

The Memory Palace: A Book of Lost Interiors by Edward Hollis (Portobello £9.99)

Edward Hollis’s ambitious book surveys the interiors of memorable buildings: from Rome’s Palatine, to Westminster, to his grandmother’s living room in her house on London’s outer ring. Hollis claims that “the history of the interior is also a history of the art of memory”; we have, he says, a propensity to arrange our surroundings so as to prompt reminiscences. The Memory Palace won comparison with W G Sebald on its initial publication, which seems to me rather extravagant: Hollis’s prose is patchy, and his arguments can be rather vague. But at its best this book makes you think anew about how the way we arrange our rooms reflects our inner lives – you’ll certainly never watch Grand Designs the same way again.

***

Critical Mass by Sara Paretsky (Hodder £7.99)

Responding to a telephone call from a distressed young woman, private detective V I Warshawski drives south from Chicago to a ruined farmhouse. She finds the remnants of a meth lab – and the mutilated body of a young man in a cornfield nearby. As V I investigates, she discovers that this is more than a drug deal gone wrong; it is evidence of a conspiracy involving Austrian nuclear physicists and geeky computer programmers. Peretsky’s plot has more twists than a ropey soap opera, but this is also a thriller with intellectual heft – Peretsky reveals a nice line in highbrow similes: one character plays on another’s sympathies “like Isaac Stern with a Stradivarius”.

****

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments