On The Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks, book review: An extraordinary zest for life

Sacks' memoir is engaging, exciting, and inspiring – just like his life so far

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

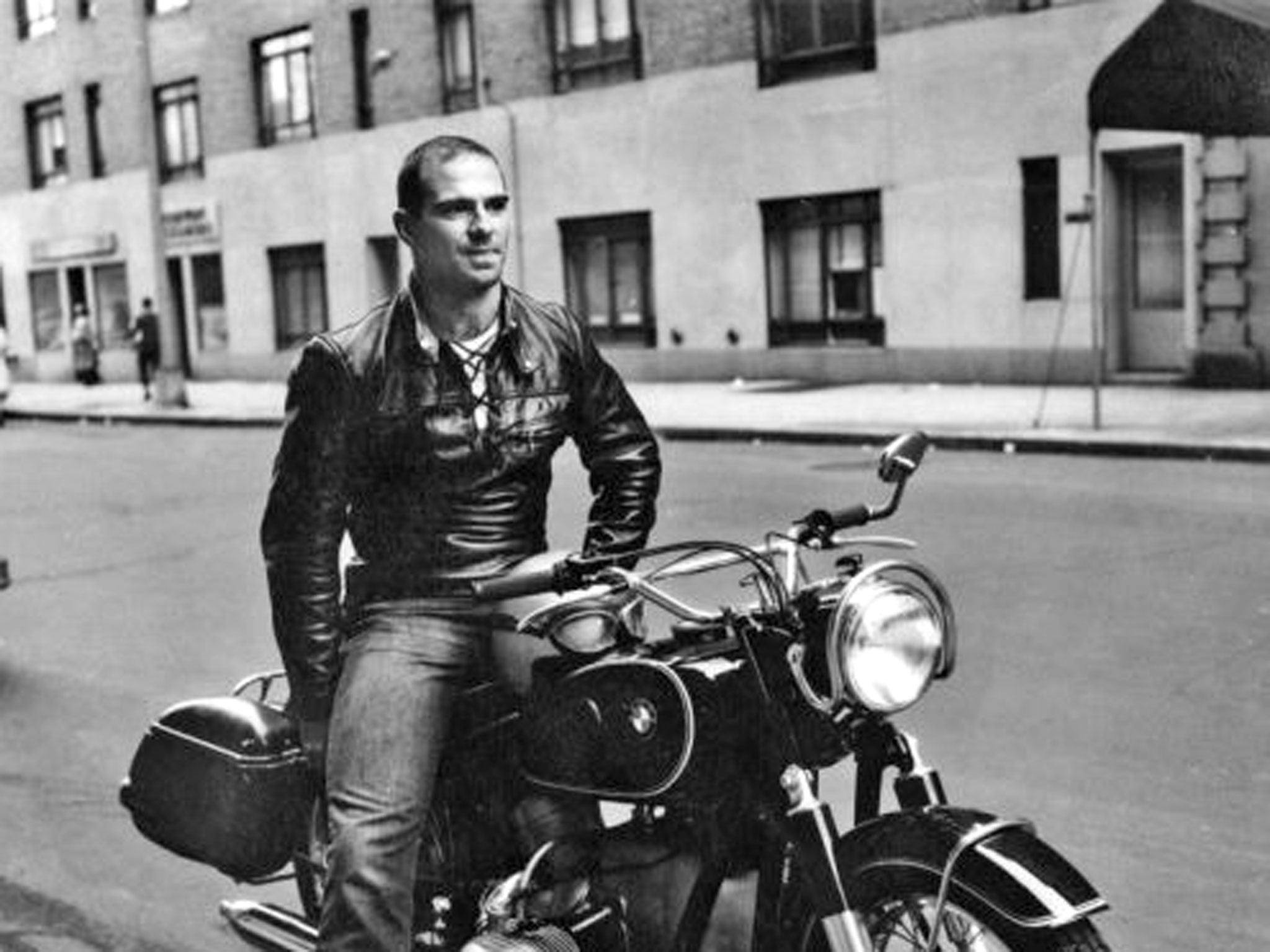

This memoir reveals Oliver Sacks as an even larger-than-life figure than I'd imagined. Literally so, because he was a champion weightlifter in his youth and an all-round man of action. Even more than weightlifting, the great passion running through his early life was motorbikes. The book begins with the power and sense of mastery they conveyed, and bike journeys and stories thread throughout the memoir.

Sacks is 81 now and was diagnosed with liver cancer in January. A recent piece in the New York Review of Books describes his successful treatment and hopes of gaining a few extra months of the kind of good life this fond – and sometimes rueful – retrospective recounts.

Sacks' zest for life has been extraordinary and, despite frankly admitting many failures and weaknesses, he has had a mostly unerring knack of hitting his targets. One of his favourite phrases is "I longed for..." and his route to the desired object has often been serendipitous. The book's title comes from a Thom Gunn poem about bikers; as a teenage motorcyclist in '50s London, Sacks was at home with the ton-up boys of the Ace Cafe on the North Circular. At Oxford, he drunkenly wandered into a physiology essay competition and won it. He broke the Californian weightlifting record for the squat.

Sacks has an excitable, impulsive, sometimes addictive and self-destructive personality. He has lived dangerously, enduring a lengthy period of drug dependence, the ravages weightlifting wrought on his body, biking and surfing accidents that could have been far worse, and scrapes that got him fired as a doctor and turned him into a peripatetic freelance neurologist-cum-writer.

On the Move is about Sacks' ruling passions, including the men he loved. He never had any doubt about his orientation and when his father queried his lack of interest in girls at the age of 18, he confessed that he preferred boys. The book deals with his love and sex affairs very touchingly, his friendships also, but he often finds himself writing throughout the book "it was only then... that I realised..." His headlong rush through life sometimes blinded him to the effect he had on those who loved him.

Despite all his other claims to fame, it is of course his work as a neurologist and a writer that brought him acclaim. What is striking, reading this account, is how Sacks' reflections on his own life meshed with clinical explorations of extreme conditions in his patients. So when he broke his leg on a mountain in Norway in 1974, his experiences of a limb temporarily lost to consciousness resulted in the book A Leg to Stand On – originally given the working title Quickenings, by analogy with his classic Awakenings, about the dramatic return to consciousness after several decades of post-encephalitic patients given the drug L-dopa. Again, he noted that the effects of this drug on the patients were sometimes similar to those he had observed in himself while on LSD.

Sacks is an unusual scientist, decrying mechanistic, competitive science and writing lovingly of the "sweet, unspoiled, pre-professional atmosphere" that figures such as Darwin, Bates and Wallace breathed. After being told that he was "a menace in the lab", he admitted the force of a remark his friend from childhood Jonathan Miller had made: "Our love of science is utterly literary".

He is a great hero worshipper with a fine judgment of which heroes to worship both past and present, including Darwin and the other great 19th century naturalists, his contemporaries Stephen Jay Gould and Francis Crick, the neurologists Salvador Luria and Gerald Edelman, the writers W. H. Auden, Thom Gunn, and Harold Pinter.

Strangely for such an adventurous giant of a man, he confesses about one third of the way through the book: "I was timid, diffident, insecure, and submissive". The rest of the book bears this out, often recording his childlike delight when some great figure praises his work. Coursing through On the Move is his constant sense of joy in the natural world, in scientific epiphanies, and people in all their oddity.

He is surely one of the most singular and inspiring men of our time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments