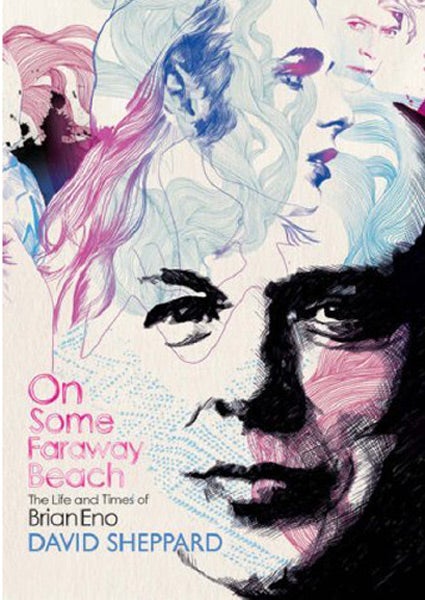

On Some Faraway Beach, By David Sheppard

A knob-twiddler's progress from Roxy Music to Coldplay via Talking Heads

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There's an epigraph in David Sheppard's meticulously-researched biography that perfectly encapsulates why Brian Eno has become avant-garde pop's best-loved backroom boy. It's a quotation from the guitarist Robert Fripp: "He's my favourite synthesiser player because instead of using his fingers he uses his ears."

Eno is the warm-hearted conceptual artist who bridged prog and punk (working with both Genesis and New York new-wavers Television in the same year) and knows a good pop song when he hears it. Fripp, no mean experimenter himself, first collaborated with Eno on the 1973 soundscape album No Pussyfooting, an abstract blueprint for much to come in Eno's extraordinarily fertile career. Sheppard spends some pages on this epochal record, pointing out that when John Peel premiered it on his Radio 1 show, using tapes provided by the artists, he unwittingly played it backwards. As the album hadn't yet hit the shops, no one but Eno and Fripp noticed the slip. It's the kind of footnote which makes this doorstopper such an engaging read.

Unfolding over 470 pages and drawing on interviews conducted with Eno and others, Sheppard's book provides the definitive story of one of rock's most fascinating figures. What emerges is a man of curious contradictions. The son of a Suffolk postman, Eno grew up in rural isolation. An instinctive loner and autodidact, he discovered music and visual art, pitching into a late-1960s metropolitan milieu of revolution and experimentation to emerge as one of modern culture's pioneering communicators. A musician who has never successfully mastered a single (conventional) instrument, cannot read notation and hardly has the singing voice of David Bowie or Mick Jagger, Eno has become, as Sheppard puts it, something of an "accidental rock star".

Eno can boast a resumé which ranges from vital synth parts on early Roxy Music releases and devising the genre of "ambient music" (while bed-bound, recovering from a road accident), to collaborations with a Who's Who of art-rockers, and production credits on mega-sellers by U2, Talking Heads and Coldplay.

We are also reminded that behind the knob twiddling is a man of enormous sex appeal and an almost predatory libido. Sheppard reports how, as Roxy tours drew to a close – to Bryan Ferry's chagrin – the fastidious lothario would pore over Polaroids of the numerous conquests he'd made on the road.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments