Of Beards and Men by Christopher Oldstone-Moore, book review

Christopher Oldstone-Moore provides a cultural history for chin-strokers

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Jeremy Corbyn's signature political achievements until last September were his five titles as Parliamentary "Beard of the Year". This beard is no mere vanity; he once described it as a "form of dissent" from the clean-shaven blandness of New Labour. It is the straggly embodiment of his "New Politics".

Christopher Oldstone-Moore's survey of facial hair through the ages omits to mention Corbyn, but he would recognise the argument that facial hair need not be affectation, or evidence of shlubbish oversight. That beards and their raffish cousin, the moustache, might express something about a wearer's political affiliations. The face, he claims, "is an index of variations in manliness", and because notions of manliness are bound up with political and social authority, facial hair is "always political".

Beards, of course, are very much of the moment: fashionable east Londoners continue to ignore warnings that we have reached "peak beard", and sport the full whiskers previously monopolised by Orthodox patriarchs. There is a sense that Oldstone-Moore, who has written several scholarly articles on beards, can't quite believe his luck at this subject's sudden pertinence. We tumble through a series of lively case studies that illustrate those changing conceptions of masculinity he supposes changing attitudes to facial hair to represent. Despite excursions into the ancient, and the contemporary, Middle East, the focus remains on Western culture: Jesus's beard; Lincoln's beard; Hitler's moustache.

"The history of men is literally written on their faces," promises the overexcited introduction: a funny way to frame a metaphor, indicative of a broader problem with this sort of cultural history. Beards are only significant because of the context in which they're grown, and too much of this book feels like a perverse attempt to redress that balance.

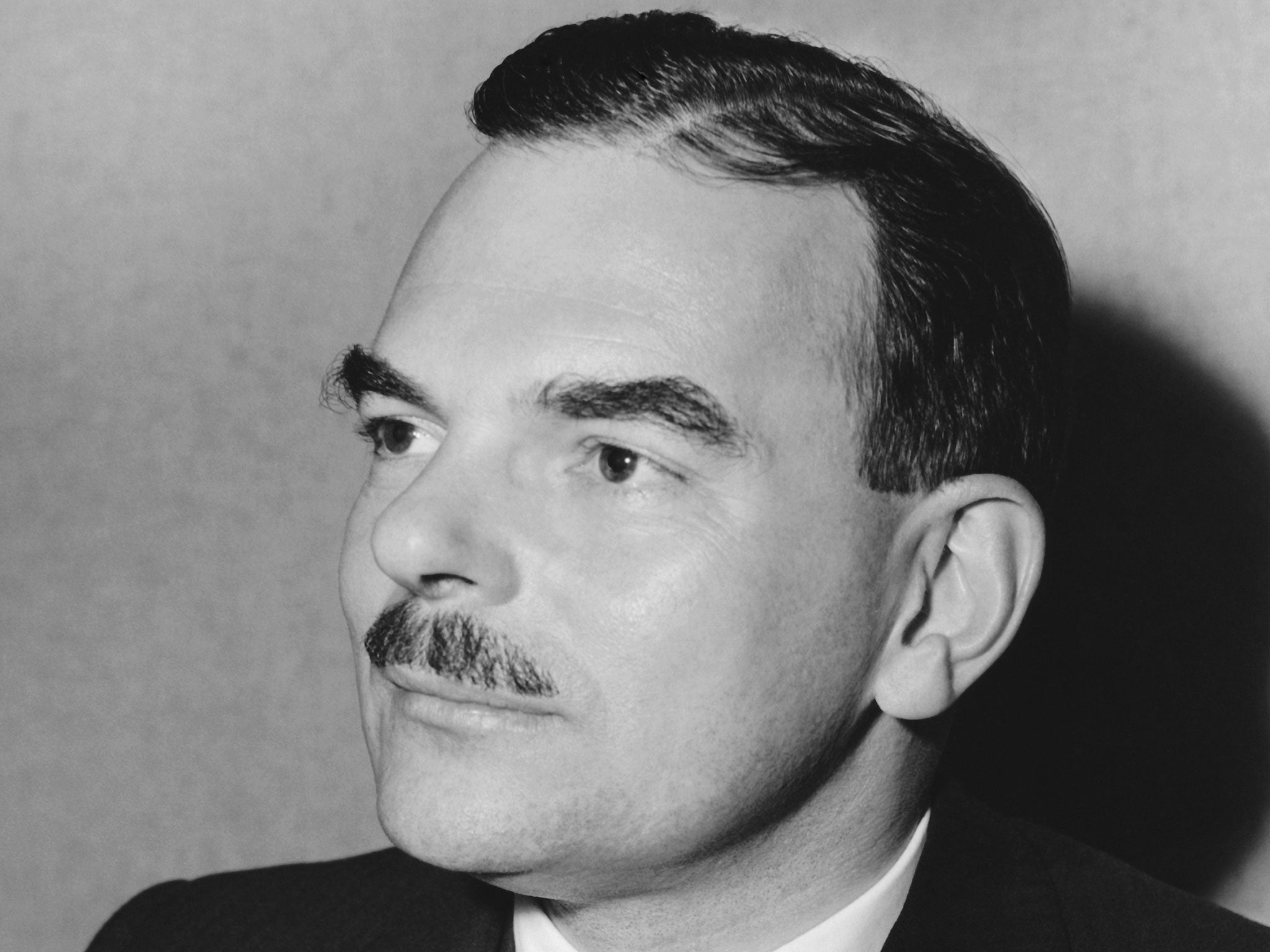

When Oldstone-Moore writes that the popularity of facial hair in the 16th century was a physical expression of Renaissance humanist ideas about the natural "dignity of man", he is more convincing than when he argues that Thomas Dewey's moustache lost him the 1948 US Presidential election. The latter, though, seems an anxious reaction to the accumulated nebulousness of observations like the former.

An Ohio housewife who said in 1948 that she "could not vote for a man with a mustache" was most likely giving voice to the widespread suspicion of Dewey's political opportunism which his roguish moustache appeared to confirm. Just as Corbyn's beard only became a symbol of dissent because he rebelled against the Labour Government 428 times. Which is to say that beards might not, as a 12th-century monk wrote, always indicate a propensity for "filthy lusts like stinking goats", but they are probably always less interesting than the people who wear them.

University of Chicago Press, £21. Order at £18.50 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments