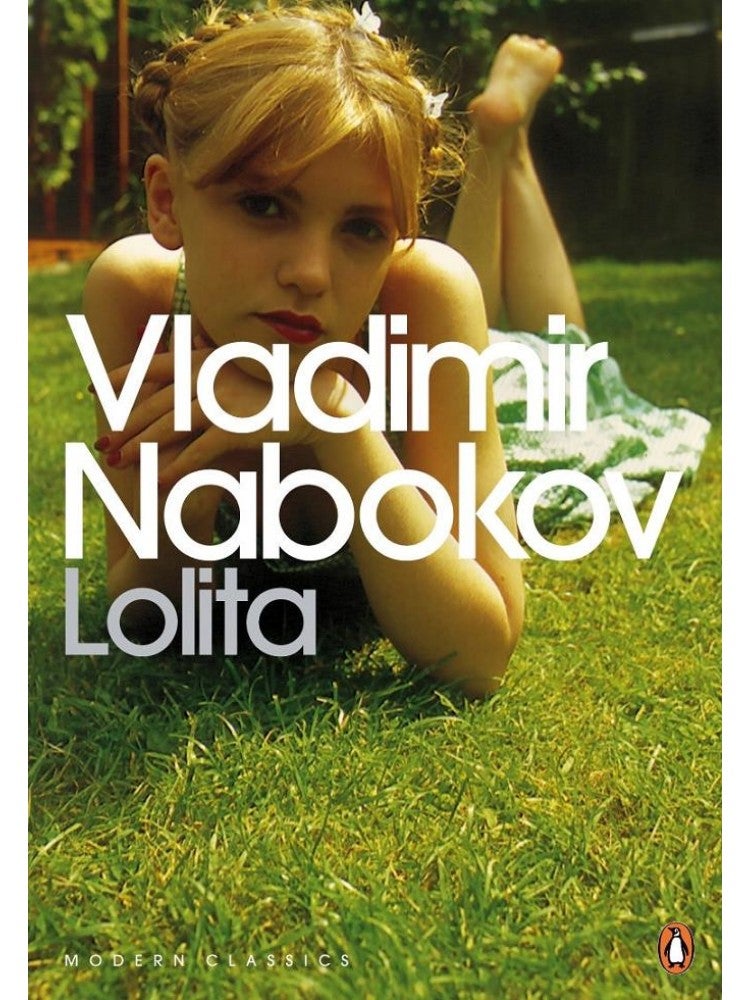

My book of a lifetime... Geling Yan: Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

'Had I not read Nabokov in English, it would have been as if I had never read him at all, because his English is utterly original and conveys his unique linguistic personality'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before I went to study abroad in America, all I had read of Nabokov was Laughter in the Dark in Chinese translation. I was favourably impressed. His language was humorous, and the narrative was permeated with the author’s maturity and wisdom, revealing his resurging joy despite his disillusionment with human nature and his condemnation of human weakness.

After I arrived in America and was assiduously studying in the second year of a Master of Fine Arts programme, I took an elective course called “Masters Who Have Once Been Banned”. This time I truly encountered Nabokov’s work. His novel that had been banned was Lolita. It was then that I realised that the Nabokov I had encountered in Chinese translation was not very “Nabokov”; the translation had washed out far too much. Had I not read Nabokov in English, it would have been as if I had never read him at all, because his English is utterly original and conveys his unique linguistic personality.

As Lolita was required reading for that course, I started reading it in class. By the time I finished it, I was on the train from Washington DC to New York. As I read the last sentence, I slowly closed the book and forgot about all the people around me, forgetting also that I am timid in the presence of strangers, and allowed the tears to flow freely.

Nabokov, with his actually not-so-flexible “infinitely flexible tongue”, had told an incomparable love story. It was an incestuous, paedophile love story that should have caused me to feel antipathy, even disgust. But by that time I had become utterly infatuated with Nabokov’s English, had completely surrendered to the hallucinatory effect of his narrative, and I abandoned all moral judgment.

I also became aware that Lolita could only have come from the pen of someone who had been exiled, because only someone forced to leave his native land could develop such a vagabond spirit, such morbid sensitivity and such an obsession with the title character.

For the protagonist, Lolita is the projection of his childhood sweetheart who died young. The concept of the homeland in the mind of a person who has lost his country in childhood sublimates itself in the microcosm. The homeland is lost, the beloved is no more; but Lolita’s small body represents for him the microcosm of his lost homeland.

This is a terribly tragic immigrant love story. I read it in America after having experienced the feeling of possibly never being able to return to my own country China after the Tiananmen Square Incident of 1989. My own condition of self-exile gave me a thorough understanding and complete empathy with the protagonist of Lolita.

Geling Yan’s latest book is ‘Little Aunt Crane’ (Harvill Secker)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments