Mimi, By Lucy Ellmann

A dark-hued but uplifting tale leads to a life beyond the cult of cosmetic enhancement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lucy Ellmann's first three novels - Sweet Desserts, Varying Degrees of Hopelessness and Man or Mango - were smart, funny, brimming with originality, awfully sad and festive in the extreme. Sex was revered, often seeming like the novels' hero. Grief was shown in all its squalor and wildness.

Get money off this book at the Independent's book shop

Rejection and abandonment were not shied away from, to put it mildly, but joy was always communicated through Ellmann's vivid intelligence, her tendency to celebrate things and ingenious use of language. Little details have stayed with me: a man's rum collection of grapefruit spoons that seemed to say so much about him; a father comforting his young daughter by regaling her with the most painful moments from his own childhood and making everything a million times worse.

Dot in the Universe and Doctors and Nurses, though likeable, contained so many soaring flights of fancy that they sometimes left this reader rubbing her head at the check-in desk. Mimi is more focused: it has a trajectory, it has a thesis, it has a hero.

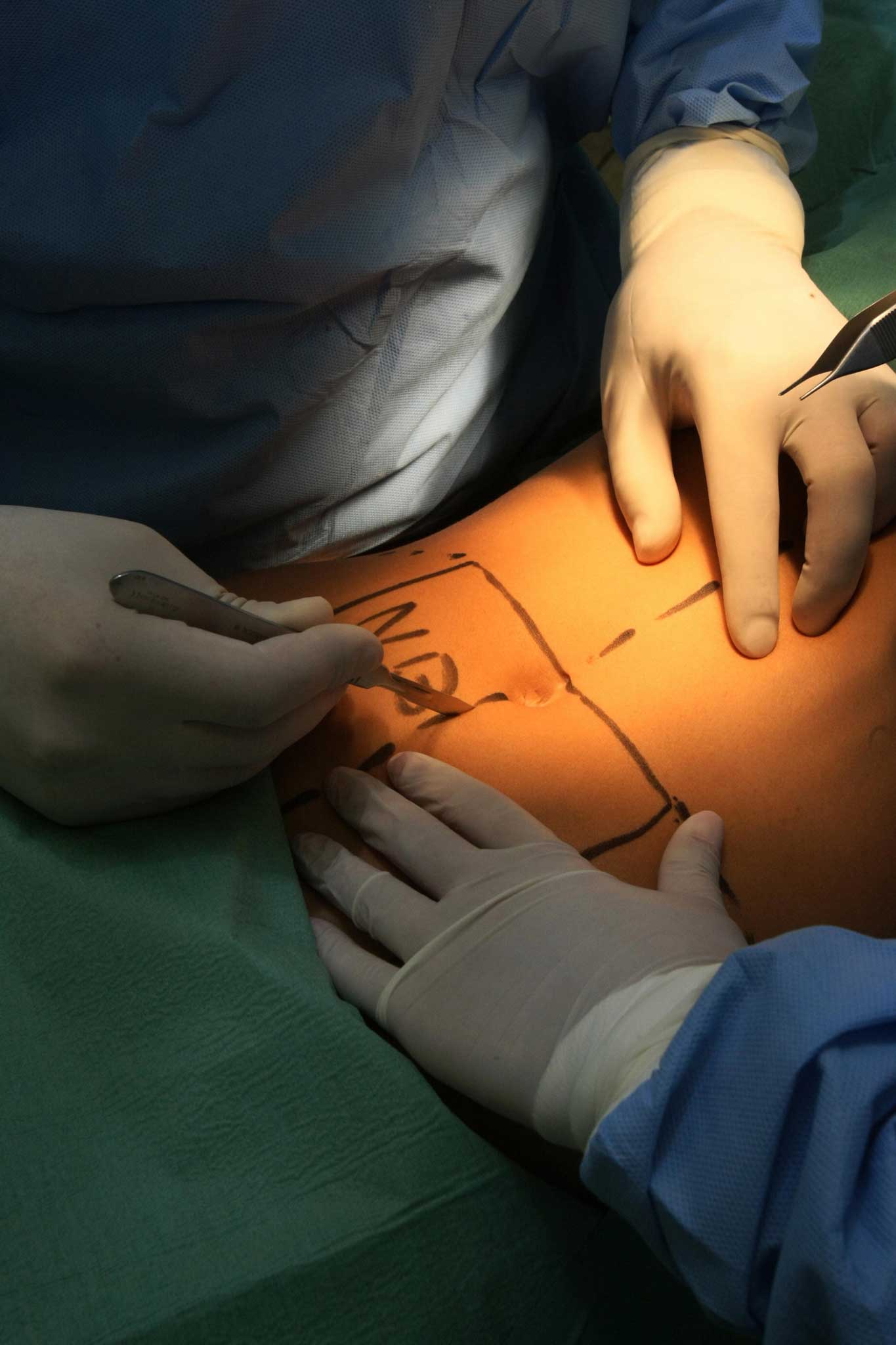

New Yorker Harrison Hanafan is a plastic surgeon, a baffled and buffeted professional who reminded me a little of the botanist uncle in Saul Bellow's best novel More Die of Heartbreak. He thinks of himself as sensuous. He has a certain moral energy. Yet he is hurt, vulnerable and afraid. The book opens as his romance with the frightening Gertrude has ground to a halt and he sprains his ankle, slipping on ice one Manhattan Christmas Eve.

Hanafan's enforced withdrawal from the world means he is free to go to town on his list-making habit. He makes Whitman-esque lists of everything: of ideas for inventions, of cures, and of things that make him melancholy, which include artist-in-residence posts, accordions and the microwave's hollow ping.

Hanafan has good reason to be melancholy for he inhabits a world where sexual violence and sharp practices are rife. An average day at his surgery sees a toddler who has been taught by her father to make sexual advances and women raped by loved-ones who have eaten their feelings and seek liposuction to conceal this development. There are girls knifed by their dumped boyfriends; women gifting their vicious husbands with new bosoms for Christmas. Even the luckier or more comfortable-in-their-skin female patients loathe themselves "according to the requirements of the era". Even ducks in the park are raped in front of children and elderly.

When the outspoken and overwhelming Mimi comes into his life, Hanafan begins to question everything. He is cut up about his former life. He realises how much he loves his sculptor sister, re-evaluates his parents' marriage, reframes a childhood disaster, and falls in love with a capital L. He also comes to see his profession as ignoble: "Sure I could turn a guy's crows feet into hummingbird talons, but there's no getting rid of his deep soul ache is there?" But to misquote Jimminy Cricket, what does a cosmetic surgeon want with a conscience?

Well, Hanafan, under Mimi's tutelage, and following a bereavement, becomes an evangelical feminist! His thesis - women, we owe them everything, all our money, all our love – causes no small number of waves. Ellmann demands a lot of indulgences from her readers. Many events in Mimi are – what shall I say - far-fetched? If this book is even darker and sadder than Ellmann's previous works it is perhaps because the world it portrays is so sick at heart. Yet Mimi is ringing with love and rage and hope. Ellmann's best sentences are so springy and rhythmic, they make you think of a Slinky coursing down the sweet spot of a staircase, happy as Larry.

Susie Boyt's latest novel is 'The Small Hours' (Virago)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments