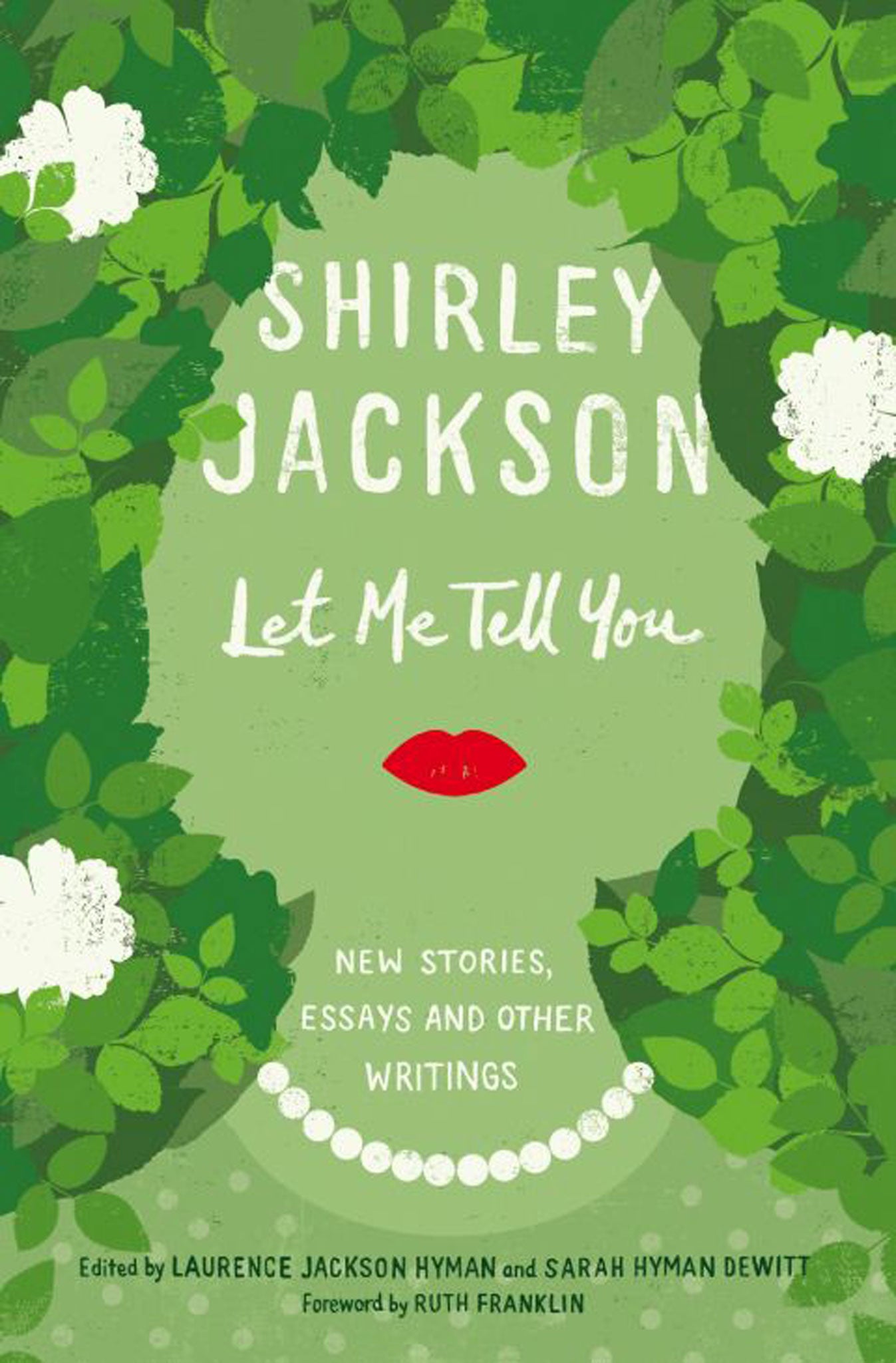

Let Me Tell You, By Shirley Jackson - book review: Horror with a warm heart

Penguin Classics - £20

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I love houses. I love to look at them the way they just stand there, and I most particularly love old and big and fancy houses.” In her essay, “The Ghosts of Loiret”, Shirley Jackson writes cheerfully about houses and poltergeists (“it is simply too much for a house to have poltergeists and children”), but as any fan of her novels knows, houses are containers of deadly evil. Both The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) stem from this idea; without Jackson’s deliciously dark domestic dramas, a whole genre would not exist.

This collection of either unpublished or once-published-but-forgotten work is valuable because it shows Jackson’s early preoccupations from the early to mid 1940s, before she came to write those masterpieces, as well as the shocking short story, “The Lottery”, published in 1949, which brought her minor fame.

What’s impressive about these stories is the quality. In “Mrs Spencer and the Oberons”, an uptight mother and housewife “can’t find” her family even though she hears them in the woods; in “The Lie” a woman goes back to her home town to try to correct a wrong. All have a circularity that suggests entrapment, a major theme of Jackson’s later works, but they also hold up as spell-binding stories in their own right. These aren’t practice works, rehearsals for the main event.

Jackson’s ability to draw out the macabre from the everyday reality of domesticity is what made her great. In one essay about the craft of writing, “Memory and Delusion”, she writes: “All the time that I am making beds and doing dishes and driving to town for dancing shoes, I am telling myself stories.” Her own house, that seemed to be benevolently haunted, inspired the malevolent happenings in the novels; even her reading matter is used – she laments the lack of time that the modern world gives Samuel Richardson’s doorstoppers, so she makes Dr Montague work his way through three volumes in The Haunting of Hill House.

The seemingly impossible alliance of warmth and horror is what made Jackson’s fiction so remarkable, and in this volume we discover a little more about how that alliance came about. She treated being a mother of four with humour and respect, whilst crafting her world into fiction, in order to make us shiver. Like the best writers, she maintained the trickiest of balancing acts, both in art and in life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments