Leonardo and The Last Supper, By Ross King

During his lean years, Leonardo saw himself as a failure in Milan – and then came 'The Last Supper'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

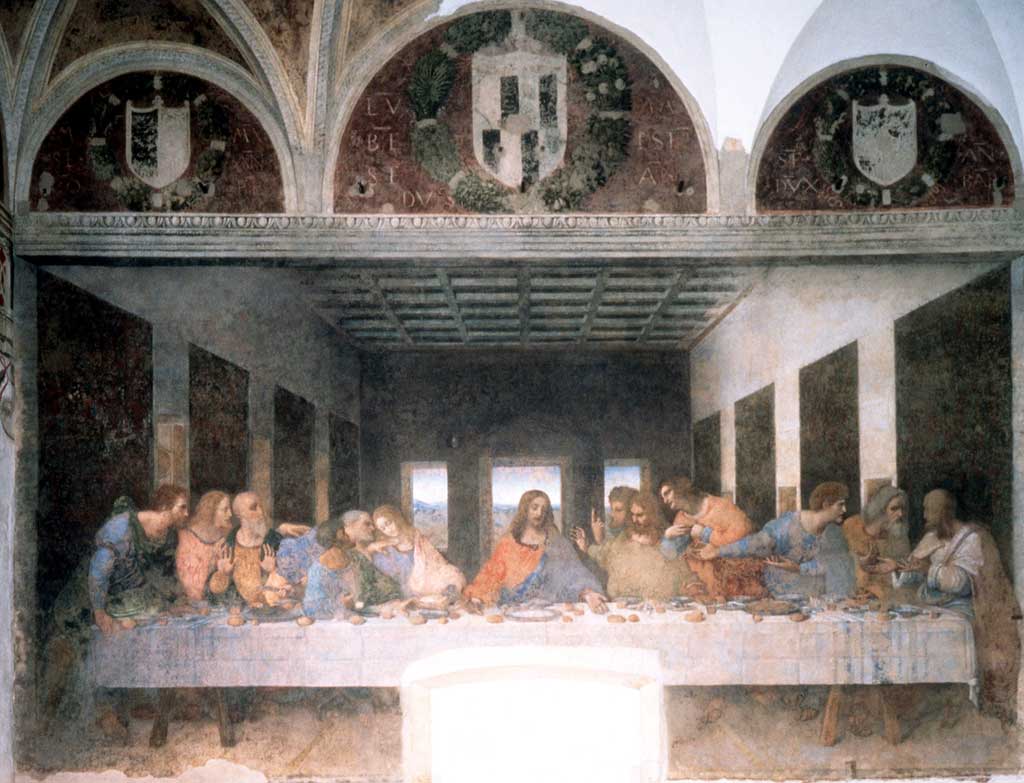

Your support makes all the difference.I wish to work miracles," Leonardo da Vinci once wrote in a note to himself. Yet, by the time he was commissioned to paint The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, he was already in his forties and felt he had little to show for it. Easily distracted by novel ideas and daring new ventures, he had seen many of his most ambitious schemes come to nothing. He had, indeed, gained a reputation for unreliability, not undeserved.

In his 13 years in Milan, among the few paintings Leonardo had managed to complete was the first version of an altarpiece, now known as The Virgin of the Rocks (the Louvre version). But the commission had been the cause of a protracted legal dispute: Leonardo, an artist for whom working to order often presented an insurmountable challenge, had failed to complete it on time.

When at last he had, his patrons were far from happy with its disquieting naturalism, at least according to Ross King. The holy confraternity who had commissioned the work for the church of San Francesco Grande had expected the Christ Child to be raised on a golden platform, with God the Father hovering overhead. A description had been written into his contract.

The Virgin of the Rocks remained in his studio long after it was finished, though a few years later, Leonardo did manage to complete The Lady with an Ermine (1489), a portrait of the Duke of Milan's beautiful 16-year-old mistress Cecilia Gallerani. There is no suggestion that this entrancing portrait met with anything but approval, and yet Leonardo himself was dissatisfied.

Aged 30, he had come to Milan from Florence in search of engineering and architectural commissions. It was 1482, a time in which the various duchies and republics of Italy were embroiled in internal machinations and bloody territorial wars with France. Leonardo had written a persuasive introductory letter to Ludovico Sforza, the future duke of the city, in which he had outlined his expertise in hydraulics and the making of war machines. His training as a painter in the studio of the esteemed Andrea del Verrocchio was barely mentioned.

But such commissions were not forthcoming. What's more, a bronze equestrian statue to honour Ludovico's father had been scuppered. It was a work that Leonardo had hoped would make his name, but instead the bronze was used to make cannons against the French. At last he received the commission for The Last Supper, but even this was viewed by Leonardo as a poor consolation prize, since it was destined to be seen by only a few monks in their refectory as they supped in silence.

It was, of course, an ambitious undertaking, and King is very good at relating the technical difficulties inherent in painting a fresco, especially for an artist who had absolutely no experience in the medium. Frescos could be tricky and were also incredibly physically demanding: they involved climbing and working on scaffolding, and painting swiftly on wet plaster. Leonardo was not a quick painter.

However, what he painted was not technically a fresco but, at 15ft by 29ft, a large wall painting on dry plaster, executed in a mixture of tempera and oil. Within 20 years it had begun to disintegrate. Today, despite numerous rescue missions, many passages have been lost forever or are barely legible.

King goes into detail exploring the models for each of the figures. But elsewhere he is often frustratingly vague and inconsistent, giving the reader tantalising nuggets but then leaving the information to dangle. Who knew that Leonardo had made an alarm clock so that it woke the sleeper by "jerking his feet in the air?" Surely we must know more.

Elsewhere, he writes that the artist played the lyre with "rare execution", but later that he "probably played the lyre". Leonardo and The Last Supper is a pacey read, but these weaknesses niggle.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments