Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The more stories I read the less certain I am about the best way to read them. Should I try to decode a story's meaning or surrender and let it take me to wherever it wishes? Is it a good thing if a story leaves me not knowing what to think?

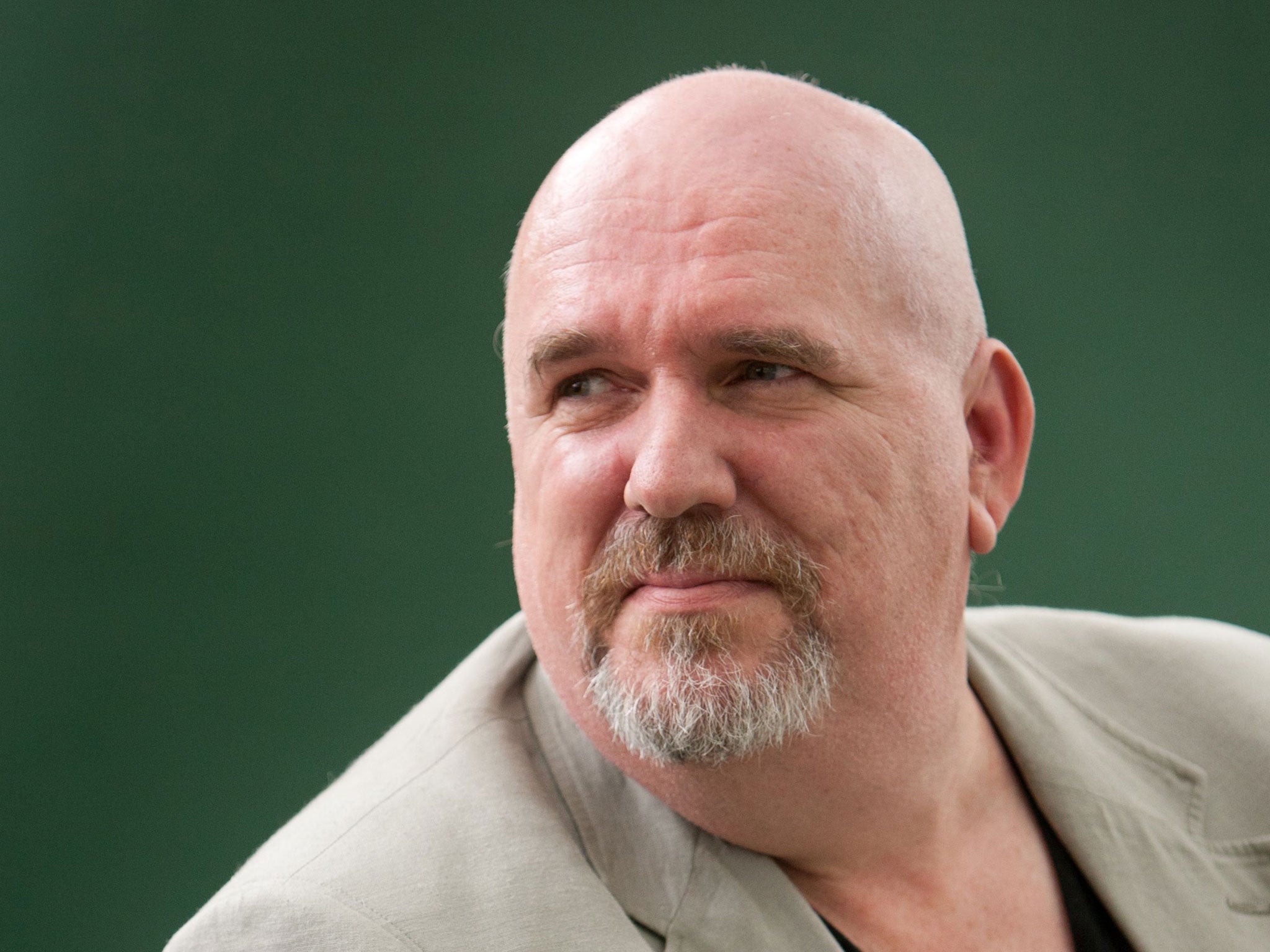

In "The Fall of Mr and Mrs Nicholson", one of the highlights of Gerard Woodward's enjoyable new collection, the narrator says: "I had written it without once attempting to understand or answer the questions it put into so many of my readers' minds." It's a wonderful story, about an author who's conscripted to write a speech for a dictator, and it indicates that stories can be as mysterious for writers as they are for readers.

Woodward's writing is accessible but never simple or sentimental. Whether his setting is a child's birthday party, the American west or an unnamed country during a violent coup, he draws the reader in immediately.

In "The Family Whistle," a woman is happily married in post-war Berlin until another man shows up claiming to be her real husband. She's been duped, he says, by an impostor who, having listened to him talk about his family while they were both prisoners of war, has stolen his life.

If this is true, is the woman complicit? Is she happier with her new husband? Either way, Woodward achieves poignancy: "Whoever was the impostor among these two, a great deal of reminiscing had been going on in the labour camp."

Loss of identity and memory are integral to the title story. Or so it appears when the narrator is contacted by a doctor about an amnesiac who's been found with nothing except a playing card with the narrator's phone number scrawled on it. Eventually, the patient comes to stay with the narrator who grows attached to him. It's an unsettling story that withholds its power until its final sentence.

Likewise, "The Night Crossing," is narrated by a man whose isolation creeps up on us. In "The Unloved," a woman who leaves her husband is inundated by dislikeable men before she finds intimacy in an unlikely place.

As well as writing stories and novels, Woodward's background as a poet is apparent in his startling imagery: ink blots are "black abscesses"; a woman is "pulled from the car as if she was a hold all"; candyfloss is "as bulky as a bright pink sheep".

His narrators display a poet's interest in pausing time, arresting motion and making solid the intangible, especially when a woman describes "a moment of love rendered in imagined architecture."

Perhaps some of this sounds more like an author's impressions than characters' perceptions. It's true that not everything works. "The Flag" owes too obvious a debt to Kafka, the depiction of the artist in "Glue" is unconvincing and some shorter stories are forgettable. But at his best, Woodward captures life's impermanence, describes fundamental human needs and demonstrates that it's possible to be surrounded by people yet feel completely alone.

Picador, £14.99. Order at £12.99 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments