Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

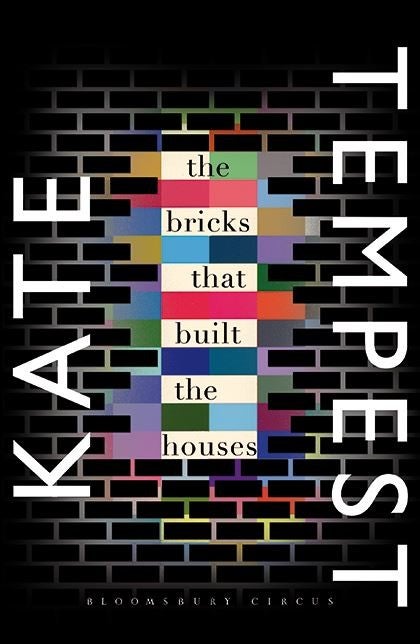

Your support makes all the difference.Over the past few years, the rap poet and playwright Kate Tempest has swept through the literary world with all the éclat of her adopted name.

With a Mercury Prize nomination and a Ted Hughes Award under her belt, it was almost inevitable that this inter-disciplinary New Generation poet would be offered a novel contract. Alas, without her rat-a-tat rhythms, she seems lost.

It’s hard not to be charmed by a novel set mostly in Deptford, New Cross, and Lewisham, the least changed (but now transforming) quadrant of inner London. Tempest has a habit of introducing the genealogy of even minor characters (ancestors being, maybe, the “bricks” of today’s inhabitants).

You can be moved by her insistence that everyone has an interesting backstory, while being irritated by the tedium of being told about it. Oh boy, does Tempest identify with the underclass. “They just want to keep everybody down,” a character opines. “Better for the government, innit, if we’re all skint and miserable and feeling like we can’t even get a day’s work.”

When Becky, a dancer, meets Harry, a business-like young woman, they are attracted enough to share dirty secrets: Becky’s a masseuse and Harry deals drugs to high-end clients.

For such rebels and free-thinkers, Tempest’s characters are strangely snobbish and condescending to anyone who doesn’t fit their own mould: the “wankers” who are Harry’s punters, the man in the Jobcentre “who’s making peace with the fact he never had any friends at school by asserting his authority over anybody he possibly can”.

Authorial sympathy is strictly rationed. Becky’s father was a firebrand left-wing intellectual who’s been imprisoned for paedophilia – a set-up, it’s implied (“They crucified him. Painted him a villain”), but where exactly does that leave the “young, crying girls” who testified against him?

The writing is a strain. Becky is “the kind of woman who starts chaos in strangers all day”, which sounds inconvenient. “Sharp financial buildings rise like fangs in the city’s screaming mouth” would not disgrace a bright 16-year-old. Just when I was thinking this makes White Teeth look like Middlemarch, about half way through Tempest remembers to put in a plot.

Some sharply written scenes ensue as Harry and Becky’s relationship ignites. Yet the tone is naïve and the south-east London underworld shown to be surprisingly soft-hearted. It suddenly struck me: Tempest is as idealistic about human nature as the poet Shelley – and just about as gifted as a novelist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments