Just Send Me Word, a True Story of Love and Survival in the Gulag, By Orlando Figes

Orlando Figes puts a personal scandal behind him to write a riveting tale of the Communist terror

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

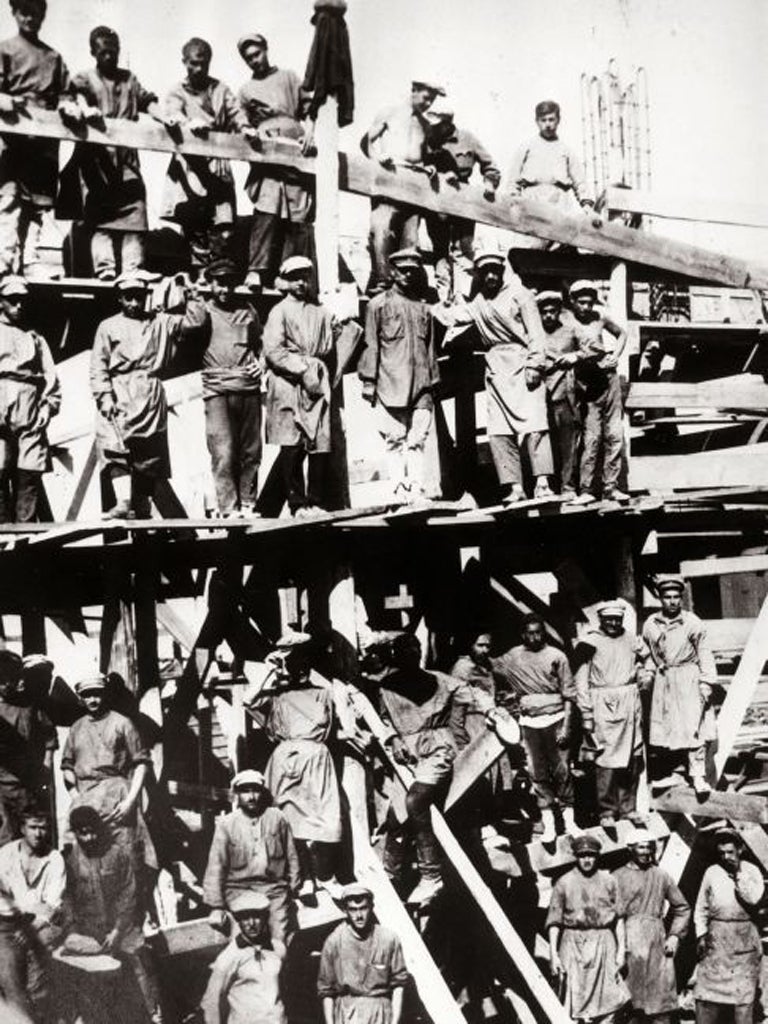

Your support makes all the difference.The gulag has never won the public profile of the Nazi concentration camps. Some 18 million people passed through the Soviet Union's labour camps. Millions died. But, for Russians and foreigners alike, there is no gulag equivalent of Auschwitz, no Russian shrine where pilgrims flock to be awed by man's inhumanity.

I have visited several Russian camps where prisoners once felled trees, hewed coal and built railways. In most places, the physical traces have all but vanished. Often all that remains are graves dotted in neat rows across the tundra, and sometimes a mound marking a collapsed barracks.

Without sites to remind visitors of the gulag's extent, it is becoming ever easier to forget it even existed. This amnesia has much to do with Russia's ambivalent relationship to its past. With a former KGB agent, Vladimir Putin, returned to the Kremlin, it is not surprising that officials are laggardly in publicising the crimes of the security services.

I have long wondered if it is the scale of the crimes that is the problem. Are they so vast that they are impossible to picture, and thus understand? Although Russian writers such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn have striven heroically to describe the experiences of the prisoners, the story they tell has almost been too enormous to comprehend. From the perspective of a Hollywood producer, the gulag story lacks individuals for us to sympathise with: a Primo Levi, an Anne Frank or even an Oskar Schindler.

Orlando Figes's Just Send Me Word may well be the book to change that. For the first time, we have a true story from the gulag that could be made into a mainstream film. Figes literally tripped over the book's source material while in Moscow on a research trip. The three trunks containing the source material were blocking a doorway in the offices of the Moscow charity Memorial. Intrigued, he asked what was in them and learned that they contained almost a decade's worth of letters between Lev and Svetlana Mishchenko, a couple separated first by the Second World, then by Lev's imprisonment in the Far North between 1946 and 1954.

In an example of the kind of love that most of us can only dream of, Lev and Svetlana remained faithful throughout their ordeal, despite the massive risks they were running. The hundreds of letters, smuggled though the barbed wire by sympathetic guards and preserved by Svetlana, are a unique record of how the horrors of Stalin's reign affected two ordinary Russians and how their love for each other kept them alive.

Even before Lev's arrest, their lives were not easy. Lev lost his parents after the revolution. He studied physics at a time when believing in quantum explanations could be enough to have you shot. He was drafted into the army, captured by the Germans, and fed into the Nazi prisoner-of-war system. Svetlana was evacuated to Central Asia, and had no idea whether Lev was even alive.

Lev only won liberation when the Americans swept through Germany. He turned down their offer to work as a nuclear physicist in the US. He wanted to get home to Svetlana. It was a decision he paid for with his freedom. Lev, like most returning POWs, was sentenced to a decade in the camps for betraying his homeland (having been captured).

At first, though he longed for his lost lover, he decided not to write to her. He had not heard from her for five years. Perhaps she had married another. But, in a moment of weakness, he wrote to his aunt asking for news. She wasted no time in alerting Svetlana.

Figes is one of the great modern narrative historians, a fact that was slightly obscured in 2010 when a scandal erupted over his posting anonymous reviews of his rivals' books on Amazon. These letters give him ample opportunity to remind any remaining doubters of his talents, however, and sometimes they are so moving that he quotes them in full, with minimal commentary. "I would only need to see that you are there when I wake up in the morning and then, in the evening, to tell you everything that had happened in the day, to look into your eyes and hold you close to me," wrote Svetlana in October 1946. "The point of all this is that I want to tell you just three words – two of them are pronouns and the third is a verb (to be read in all the tenses simultaneously: past, present and future)."

The letters detail Lev's friendships, Svetlana's career, the small kindnesses that made life possible; the cruelty and incompetence of bureaucrats that made life hard. Svetlana, indomitable and formidable in equal measure, insisted on coming to see him several times without official permission: acts both insanely dangerous and wildly romantic.

They gave each other enough hope to keep going until Stalin died in 1953. The initial amnesty that followed his death was not wide enough to cover Lev, causing him to worry that he would not survive to make it home. He survived his last Arctic winter, however, finally winning release in July 1954. He dashed south without even waiting to obtain the proper passport from the police.

They married in September 1955, two decades after they first met. "I wouldn't recommend you marry him," the woman at the registry office told Svetlana, who just smiled. They lived happily ever after, surviving long enough to meet Figes and tell him their story in their own words. They are buried side by side.

These letters summon up a world of pettiness, brutality, ignorance and fear, both more touching and more comprehensible than a grand historical narrative can ever be.They give insights into people at their worst – in Lev's words: "in 999 instances out of a 1,000, the common principles of decency lead the average person to ruin or starvation in the struggle to survive" – but also show people at their best. They describe how love evaded every barrier erected against it and defied Joseph Stalin.

They give real-time, uncensored colour and life to the gulag, a world that has previously been mostly described in statistics, reminiscences and official reports. In the early 1950s, at its peak, the gulag contained more than 2.5 million people, two percent of the Soviet Union's entire labour force. That is the kind of vast statistic that dulls comprehension.

The letters between Svetlana and Lev remind us that those prisoners were human, and so were their guards and their families. Svetlana and Lev did not mean to create a lasting memorial to the victims of the gulag, but that is what they have done, and Figes has achieved something extraordinary in allowing them to do it.

Oliver Bullough is the author of 'Let Our Fame Be Great: journeys among the defiant people of the Caucasus'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments