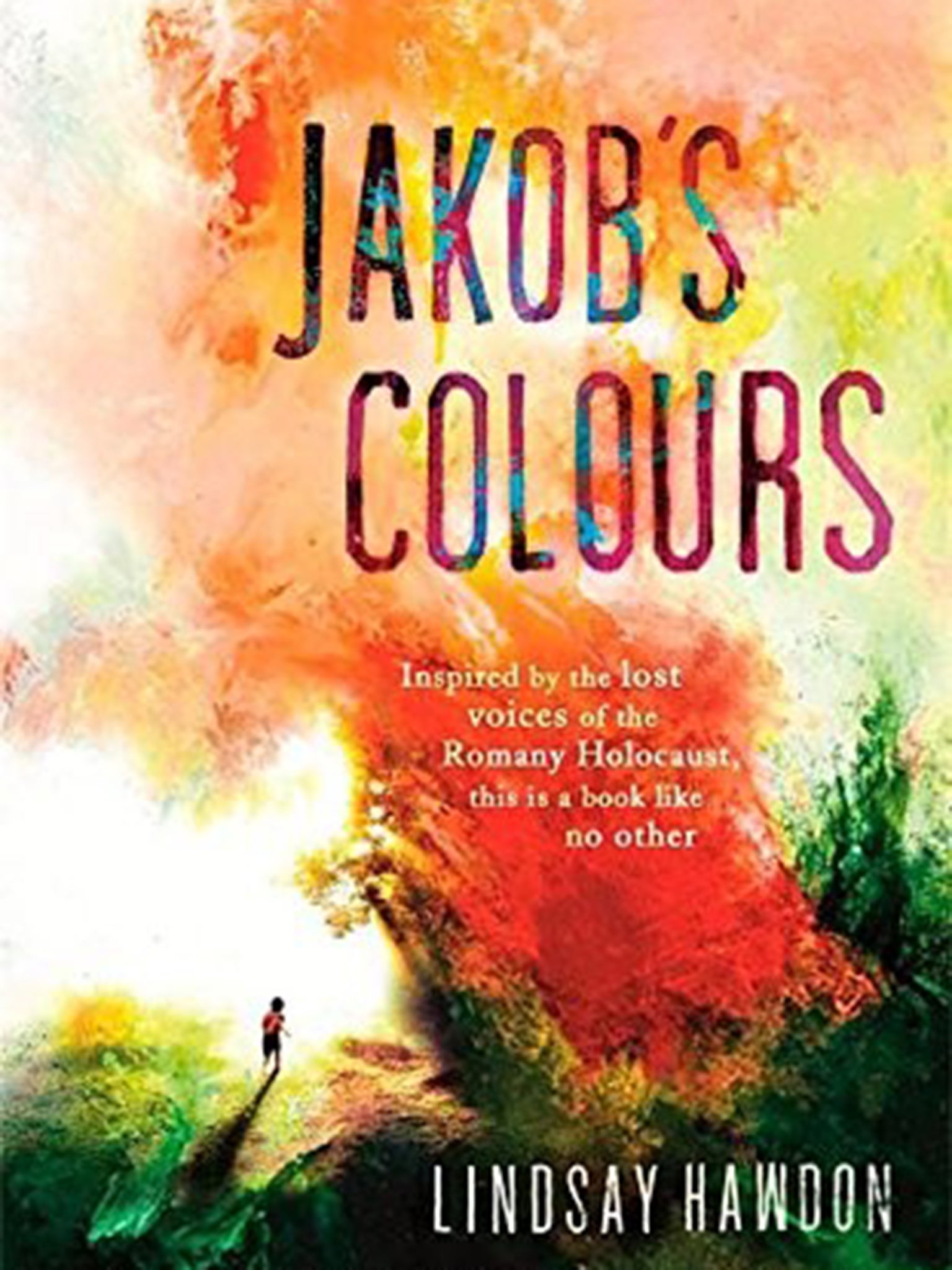

Jakob's colours by Lindsay Hawdon - book review: Hope in his pockets

Reminiscences pierced by the ugly intrusion of the present

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Someone panicking is advised to connect with the physical objects around them, to pin themselves to reality by touching a sleeve or a chair. Jakob is an eight-year-old gypsy, fleeing the Nazis. He carries pebbles and glass, drawing solace from their texture and colour.

As Jakob hides in the Austrian woods, we enter a fairy tale, with the classic scenario of the child lost in the forest. He hears “the ghost-hoot of an owl. Breeze-blown branches and the creaking of trunks.” And just as this fairy tale has its wolf, the Nazis, it also has its wizard, Yavy, Jakob’s father, who creates paints by grinding rocks and roots. He “discovered the magic of salt. Mixed it with mauve-tinged azures, violent reds … found vermilion sunsets in mercury sulphide, fired them to an orange cinnabar”. Colour offers sustenance for the frightened boy in this land of barbed wire and mass graves. Colour is memory but it’s also hope.

The novel has three narrative threads. As Jakob flees, and Yavy looks back to his gypsy childhood, we also have the story of Lor, Jakob’s mother. Her tale begins in 1920s Somerset, full of the comforting clutter of middle-class life, of “silver spoons, Worcester china and George III silvershelled ladles”. But she is sent to a clinic in Austria in the 1930s, throwing her from the safety of England into the dark fairy tale.

Spreading the story across time and space, from the 1920s to the 1940s, from England to Austria and Switzerland, creates a stuttering effect, slowing the narrative, but we soon accept that this is how memory would function, reminiscences pierced by the ugly intrusion of the present.

The book’s fairy tale tone, and its themes of hope and beauty, are matched by Hawdon’s poetic language. We see “a sky of rubbed chrome” and a lake which “glistens in the half-moon light, honey-coloured, with a promise of tranquillity”. Yet the author doesn’t carry this fluency into her dialogue which sounds strained, never natural.

This is particularly true in the case of Yavy, who says such things as: “They been saying that of me. But I knowing I not mad. Been here years ’nough to know it.” At times, this stilted dialogue seems to want to force itself into something poetic, creating more oddities.

Don’t look to this novel for a pacy narrative. Instead it’s about the whorl of memories that surround and sustain us. With such psychological clout, a twisting plotline would be mere decoration.

Hodder £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments