Iron Gustav: A Berlin Family Chronicle by Hans Fallada, trans. Philip Owens, with Nicholas Jacobs & Gardis Cramer von Laue, book review

A Berlin Everyman embodies decades of turmoil in this epic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

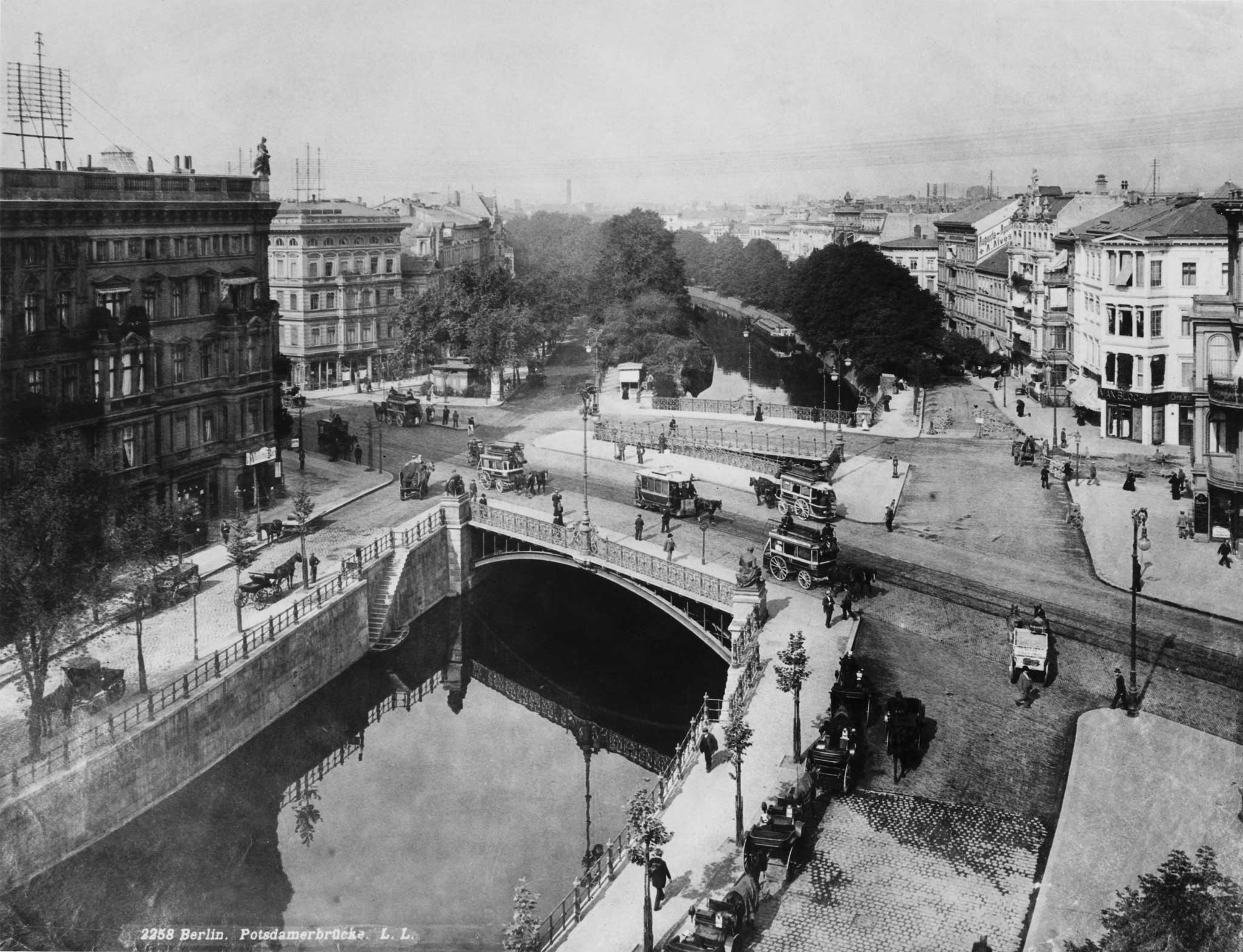

Your support makes all the difference.Gustav Hackendahl, a gruff, domineering emperor among Berlin's old-school cabmen, loses his stable of 32 horse-drawn carriages during the First World War. Still, he believes above all in "decent work". Eva, the favourite among his five insurgent children but now sliding into prostitution under the sway of her depraved lover-pimp Eugen, protests. "Decent work indeed – it was always duty, obedience and punctuality – but it was all wrong, Father." And "Father", we soon learn, "meant discipline, criticism, the sternest justice".

Both authoritarian ogre and loveable curmudgeon, "Iron Gustav" trots in his retro cab (he loathes the new-fangled motor car) through almost 600 leisurely but entertaining pages of this Berlin family saga. He is both hero and villain. This bewhiskered symbol of old Prussia has, laments smart but crooked son Erich, "beat any sense of free will out of us". Yet, tireless, loyal and never short of a quip, the patriarch of wise-cracking, working-class Berlin survives to embody not just his city's but his nation's "will to live". Behind this double identity lie all the contradictions of Gustav's creator – and the pressures of his time.

When Michael Hofmann's translation of Alone in Berlin became a huge surprise bestseller for Penguin, it opened the door for English-speaking readers to discover more of Hans Fallada's works. A gifted, prolific but deeply troubled writer, Fallada had the tragic misfortune to hit his stride as a fictional interpreter of post-First World War Germany just as the Nazis began their ascent. Whereas Alone in Berlin emerged in 1947 after his lonely years of "inner exile" under the Third Reich, Iron Gustav was swept into the eye of the storm.

Emil Jannings (superstar of German film) sought a meaty part. In 1937, after Josef Goebbels had approved his previous novel, Wolf Among Wolves, Fallada set to work on Iron Gustav with a view to adapting it rapidly for the cinema. Some of the most gripping of its dialogue-driven scenes of Berlin life between 1914 and 1928, from the revolutionary chaos around the Reichstag in November 1918 to the dole-office ordeals of upright son Heinz, could transfer straight to the screen. Goebbels, however, demanded an arc that led from defeat through Weimar decadence and into swastika-branded redemption. Fallada did the minimum to satisfy the Nazis (this edition omits the propaganda sections he later added), but he still fell out of favour.

For all his stalwart courage, Iron Gustav wrecks his children's lives. Otto dies at the Front; Eva declines into the archetypal fallen woman; Erich cheats and smarms his way through revolution and recovery. Heinz (for Goebbels, the potential Nazi) keeps the flame of virtue alive; his humiliations as one unemployed "grain among millions" prompt the finest passages in the chronicle. And ice-hearted Sophie becomes a nursing-home Matron, with the tyrant-father in her power.

The "hundreds of deep rifts" that tear defeated Germany apart play out in microcosm within the old cab-driver's family. Not even the final, fantastic episode in which Gustav drives to Paris as a celebrity, the "oldest Berlin cabby" with humour and horse intact, can mask these divisions. As he shuffles melodrama, farce and documentary realism, Fallada never stints on "end-of-the-world cheerfulness". But this, as even Dr Goebbels must have seen, is laughter in the dark.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments