IoS paperback review: Life and Death are Wearing Me Out, By Mo Yan (translated by Howard Goldblatt)

Never mind the controversy feel the fiction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

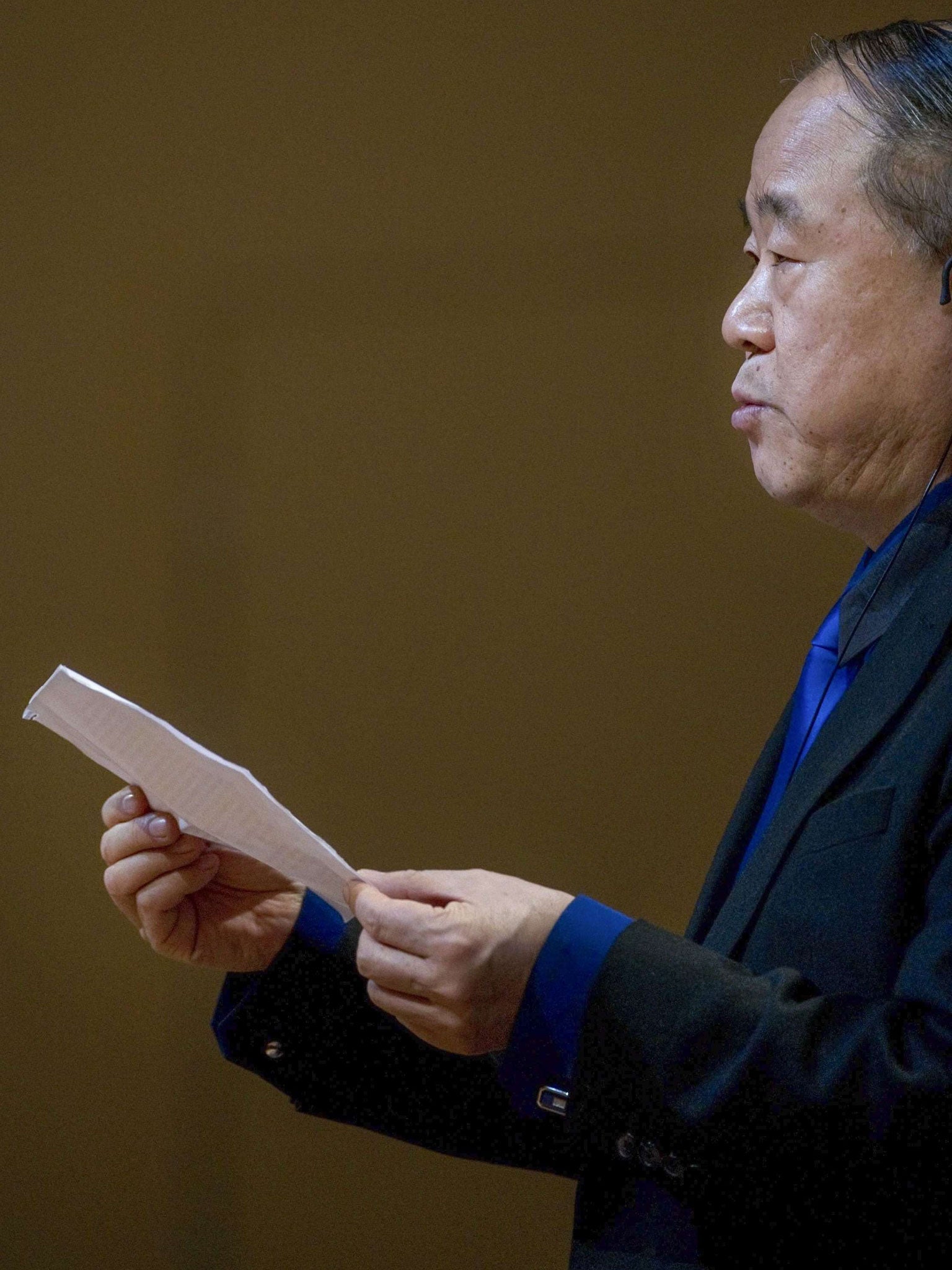

Your support makes all the difference.When, in October last year, the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Chinese author Mo Yan, the decision proved contentious. Commentators both inside and outside of China denounced Yan's ambivalent stance on state censorship and his failure to speak out in support of dissidents. Indeed, Salman Rushdie went so far as to call him a "patsy" for the Chinese government.

The strange thing about this furore is that, through it all, Yan's work has scarcely been mentioned. For those who would like to make up their own minds about this controversial writer, Life and Death are Wearing Me Out (2006), reissued here by Arcade Publishing, is a good place to start. Set in a rural village in Yan's native Shandong province, it recounts the life, or lives, of Ximen Nao, a landlord executed by peasants after Chairman Mao takes power. Reincarnated as a series of domestic animals – donkey, ox, pig – Ximen witnesses the "mighty torrent of collectivization" and its effects on subsequent generations.

This mad, sweeping, rambunctious novel feels utterly modern, or rather Postmodern, in its playful reflexiveness (there is an arch self-portrait of the author as a simpering, "unbelievably ugly" hack despised by his peers). But Yan is also responsive to the older storytelling traditions of folklore and myth, and to the more ancient rhythms of the land itself. His interest is in circularity and rebirth rather than socialist teleology – which may help to explain both his eschewal of politics and the rich, earthy power of his fiction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments