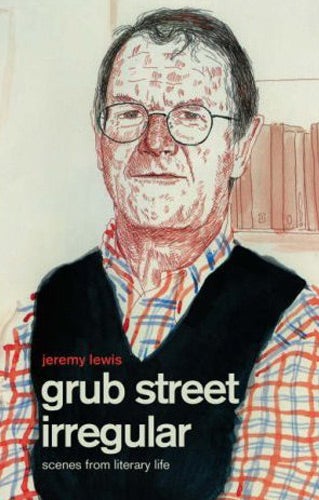

Grub Street Irregular, by Jeremy Lewis

An agile memoir enriched by the lives of others

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.English memoirs often thrive on self-deprecation. Nicely deflationary, slightly subversive, and often very funny, it is a coin of exchange favoured by James Lees Milne, Cyril Connolly and Michael Holroyd. Yet the historian and poet A L Rowse is quoted in this book, warning the author against this "very middle-class" habit.

Jeremy Lewis successfully ignores his advice. "As a child, I excelled at nothing, and little has changed since then," begins his third memoir. Readers of Playing for Time and Kindred Spirits will know that at one time he was "England's most ineffectual literary agent"; and that his skills as a publisher fell short of memos, meetings or engaging with feigned delight or rage about matters he felt were neither here nor there.

Yet his former claim to "unfocused literary ambitions and no very strong sense of purpose and direction" is a thing of the past. He has found a niche in literary magazines, at the same time writing not just memoirs but biography, too. He earned his spurs with a richly entertaining life of Cyril Connolly. Earlier, Lewis had fostered a dislike of biography as "inherently second-rate and second-hand". But a publisher's suggestion, the attraction of Connolly's merciless self-knowledge and romantic yearnings and encouragement from Connolly's widow won Lewis round. He became prouder of a calling that attempts "the resurrection of the dead, and what could be more miraculous than that?"

It also gives him an opportunity to add to the vignettes that enliven his memoirs. In Kindred Spirits he memorialised two powerful women publishers – Norah Smallwood and Carmen Callil. Here it is Barbara Skelton, Connolly's second wife, who delights and appals, flirting with him and blaming him for every disaster.

Some of the characters Lewis revives are half-forgotten literary figures, yet so agile is the writing that the reader's interest is always engaged. The memoir offers a portrait of London literary life over the past 40 years, together with an astute reflection on publishing today. Lewis also takes us inside the office of the Literary Review, revisits the garden shed in which Alan Ross edited the London Magazine and calls on the last member of the Bloomsbury group, Frances Partridge. It is the combination of percipience, self-knowledge and a readiness to admit sadness that gives this book real stature, the self-deprecation not veiling authenticity but forming part of it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments