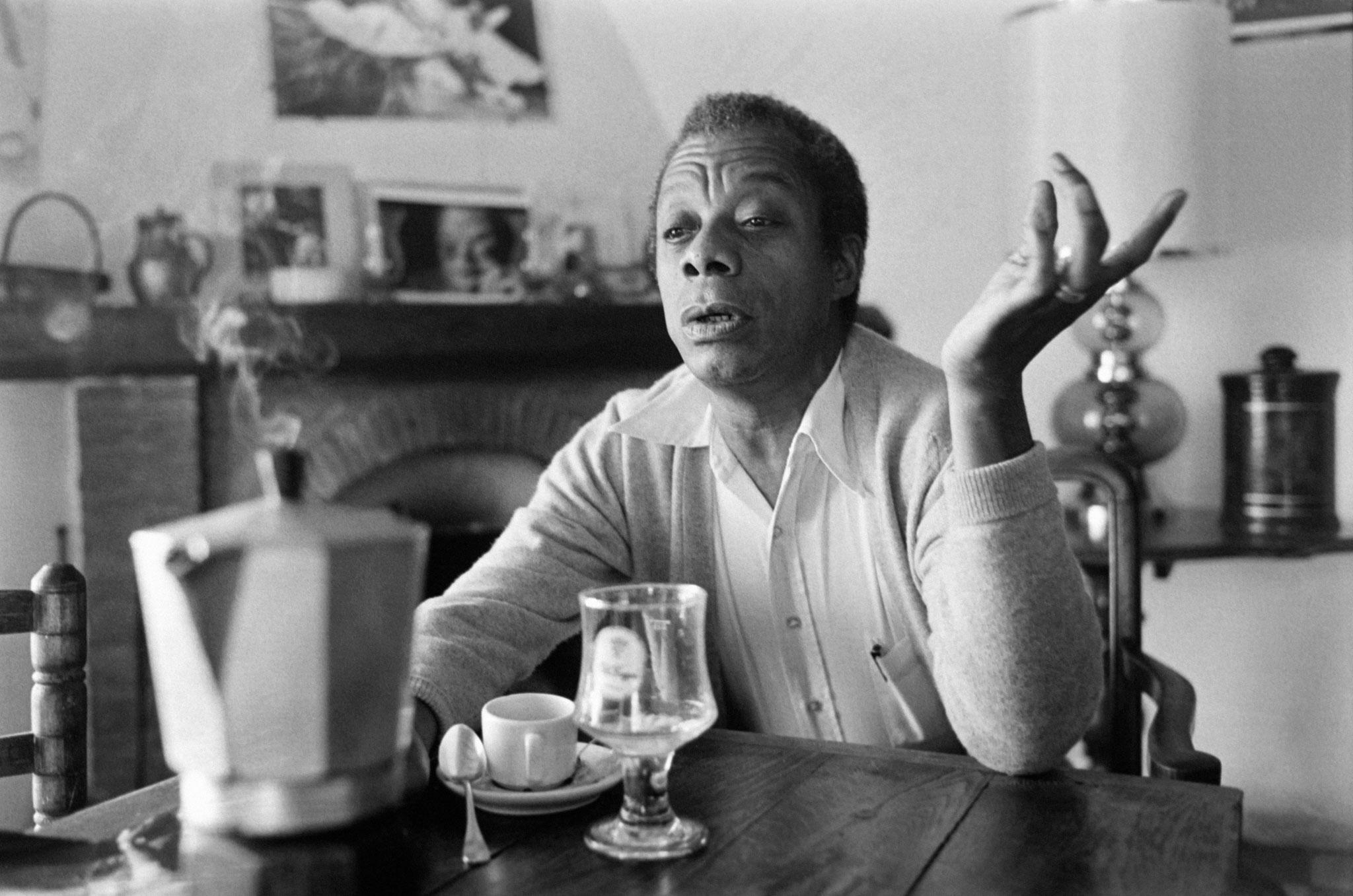

Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin, book of a lifetime: Passionate writer captures an essential aspect of life in America

The book should, like JD Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye, have been crowned as the Great American Novel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I first read James Baldwin's Go Tell It on the Mountain in my sophomore year of college, when Giovanni's Room got me hooked on Baldwin. It broke my heart and made me want to jump up and down, unable to fully articulate my own response towards it.

It is a semi-autobiographical novel that tells the story of one day (his birthday) in the life of the poverty-stricken 14-year-old John Grimes, mostly spent roaming the streets of New York and reflecting on the various demons ruling over his life: his violent preacher stepfather, his church, and the racist society into which he had the misfortune to be born. It captures an essential aspect of life in America, its contradictions and seductions, that bittersweet mix of love and hate that so many feel towards the country.

I believe it should, like JD Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye, have been crowned as the Great American Novel. Instead, it established Baldwin as a prominent black writer, a safe niche many thought, except that Baldwin disappointed them and his publisher when he chose to write his next novel about a gay white man living in Paris. His agent suggested he burn the book. Baldwin's response was "fuck you," and he went on to publish the novel first in England.

Baldwin, both as a committed civil rights activist and a passionate writer, refused categorisations by race, gender, religion or political ideology. I empathise, having experienced a similar backlash on a much smaller scale, when I disappointed expectations about what a woman from a Muslim majority country should write about. I was not black, poverty-stricken or gay, nor was I at the time an American, but Baldwin touched me like a close relative you never knew you had. And isn't that the whole point of great works of art, not only to celebrate difference, but to discover your shared humanity?

This notion of a shared humanity in fact consumed Baldwin, and infused everything he did and wrote. Claiming to be a "bastard of the west," he remained illegitimate all his life: rebelling against his false father, his false heavenly father, and his false "White father," by refusing to play their game. Deprived of heritage and history, he borrowed freely and created his own unique language, with the cadences of Bible and of jazz and Negro spirituals, and inflections of James, Dickens and Shakespeare.

Azar Nafisi's 'The Republic of Imagination' is published by Heinemann

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments