Ghosts of Empire: Britain's Legacies in the Modern World, By Kwasi Kwarteng

The men who made an empire, and left the world in the pink

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Kwasi Kwarteng was selected as the Tory candidate for the safe seat of Spelthorne in 2010, he was described (by his team and by a local newspaper) as a "black Boris".

Perhaps it takes someone who resembles London's mayor in both intellectual self-confidence and occasional mischievous perversity to present his central argument as being immensely controversial: that the raison d'être of the British Empire was not to bring the benefits of liberal democracy to its grateful colonies. Apart from the historian Niall Ferguson (whom Kwarteng quotes), one would have thought it hard to find anyone, nowadays, who believes that this was the Empire's purpose. Or does this still count as a "daring" view in Conservative circles? One must hope not.

Either way, Kwarteng takes an amusing and mostly well-written tour d'horizon through six former colonies, making a good case that Britain frequently found itself unintentionally in possession of new territories through the actions of individuals whose policies had either not been thought through in Whitehall, or not sanctioned, and which were often semi-reversed by successive "men on the spot" whose governance of these far-off regions granted them power and authority "usually reserved for the Almighty".

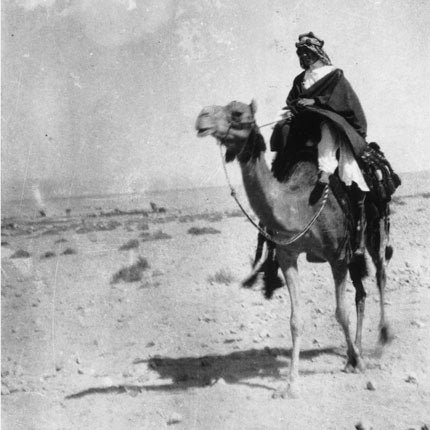

The men who painted the map of the globe pink made great Boys' Own heroes – General "Chinese" Gordon at Khartoum, Lawrence of Arabia, who was largely responsible for making the new states of Jordan and Iraq pro-British monarchies – but some of them had such strange upbringings that quirks of character were almost to be expected. Lord Kitchener's father, for instance, was so averse to bedlinen that he insisted his family use newspaper instead of blankets.

Their motivations were varied. Some, like those of the Colonial Secretary Lord Moyne, were noble. "There is no doubt that in the minds of many coloured people we are fighting ... [for] the equality of all races in contrast to the Nazi idea of the Herrenvolk," he wrote in 1941. "I feel that we must be very careful to live up to what is expected of us."

Others were short-sighted or thoughtless to the point of lunatic irresponsibility. Kwarteng is far from alone in believing that Burma, the final conquest of which was undertaken for no better reason than that Lord Randolph Churchill fancied the idea, may have had a far less tragic post-independence history had the country's monarchy not been exiled – an illogical reversal of traditional British policy of supporting "native princes". Likewise, Kashmir's troubles owe much to Britain's decision to "sell" the Muslim-majority state to a Hindu dynasty in 1846.

Kwarteng displays an encyclo-paedic knowledge of the public schools that he argues did so much to build the empire. They are both the heroes and the villains of this story, as Kwarteng clearly admires the character of their products but thinks that their self-confident individualism led them to take too many decisions without reference to the centre; the results of which are the messy legacies of empire that he details in his book.

But one good thing did come of the empire, of course. It gave us Dr Kwarteng – Eton, Cambridge and the Tory benches, and self-proclaimed "black Boris". We can all agree we need one of those, surely?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments