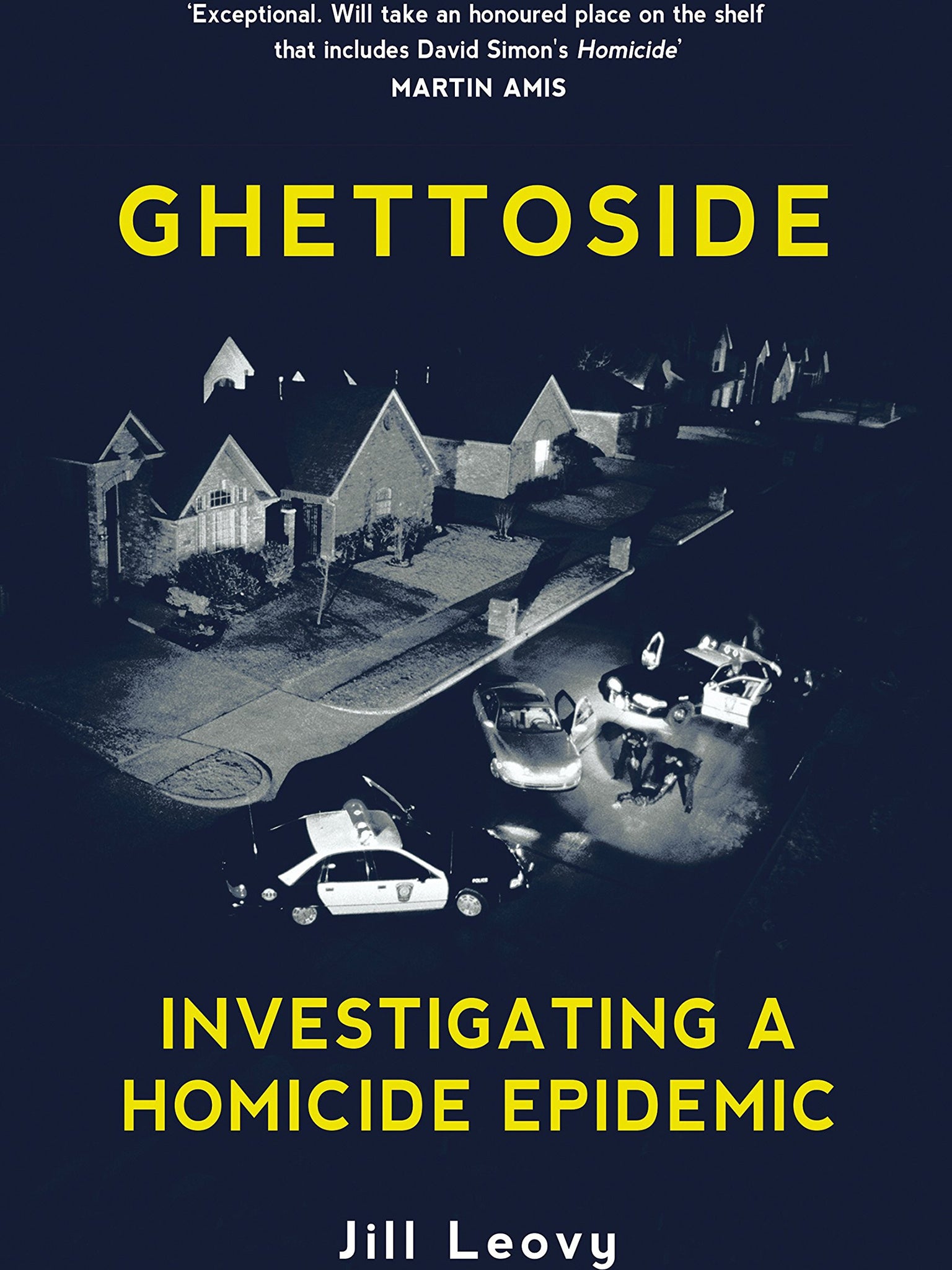

Ghettoside: Investigating a homicide epidemic by Jill Leovy, book review: Exposing the murder divide

Leovy brings all that data about death to life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Black people are America’s “number one crime victims”. They are the people harmed “most badly and most often”. And, they are killed at more than seven times the rate of all other racial and ethnic groups combined. Black lives, it seems, are cheap.

An award-winning journalist for the Los Angeles Times, in 2006 Jill Leovy started a blog, “The Homicide Report”, to cover every single murder in LA County over the course of one year. She wanted no story to go untold.

In Ghettoside, that story is the 2007 murder of Bryant Tennelle – the 18-year-old son of a policeman, shot in the head yards from his house, in what was later found to be a case of mistaken identity.

The best-selling detective novelist Michael Connelly is an admirer of Leovy’s work, and it’s not hard to see why. By shining the spotlight squarely on the key players of this real-life drama – and, admittedly, allowing their impassioned voices to take precedence over her own, cooler style – Leovy brings all that data about death to life.

Her leading man is John Skaggs, a white LAPD cop who worked the 77th Division in South Central Los Angeles. A man who solved 90 per cent of cases he investigated, Skaggs was in a different league to those “forty per center” detectives who gave up at the first sign of trouble.

Leovy is good on numbers and on context, but America’s history of empowering law enforcement workers to go through the motions – appearing to be acting, then overcompensating by “rounding and roughing up” – is best summed up by others.

She quotes the 20th-century social scientist John Dollard, who wrote: “One cannot help wondering if it does not serve the ends of the white caste to have a high level of violence in the Negro group.” White people “had the law” and black people didn’t.

Leovy’s description of Skaggs at the murder scene is almost noirish – “As usual, not much. No body. Just an empty street, and a pair of dusty black tennis shoes strewn on the asphalt” – but Ghettoside is no whodunit, and Leovy’s denouement suffers slightly for a lack of tension.

Skaggs cracked the case. But when the verdict comes in and justice is served, Leovy elevates her story beyond crime fiction. She succeeds by having us imagine how different things would be if every victim had “A John Skaggs Special”. They would not be numbers. They would not be anonymous.

Their lives would be expensive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments