Flood of Fire by Amitav Ghosh, book review

Amitav Ghosh concludes his Ibis Trilogy by examining the run-up to the Opium wars

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

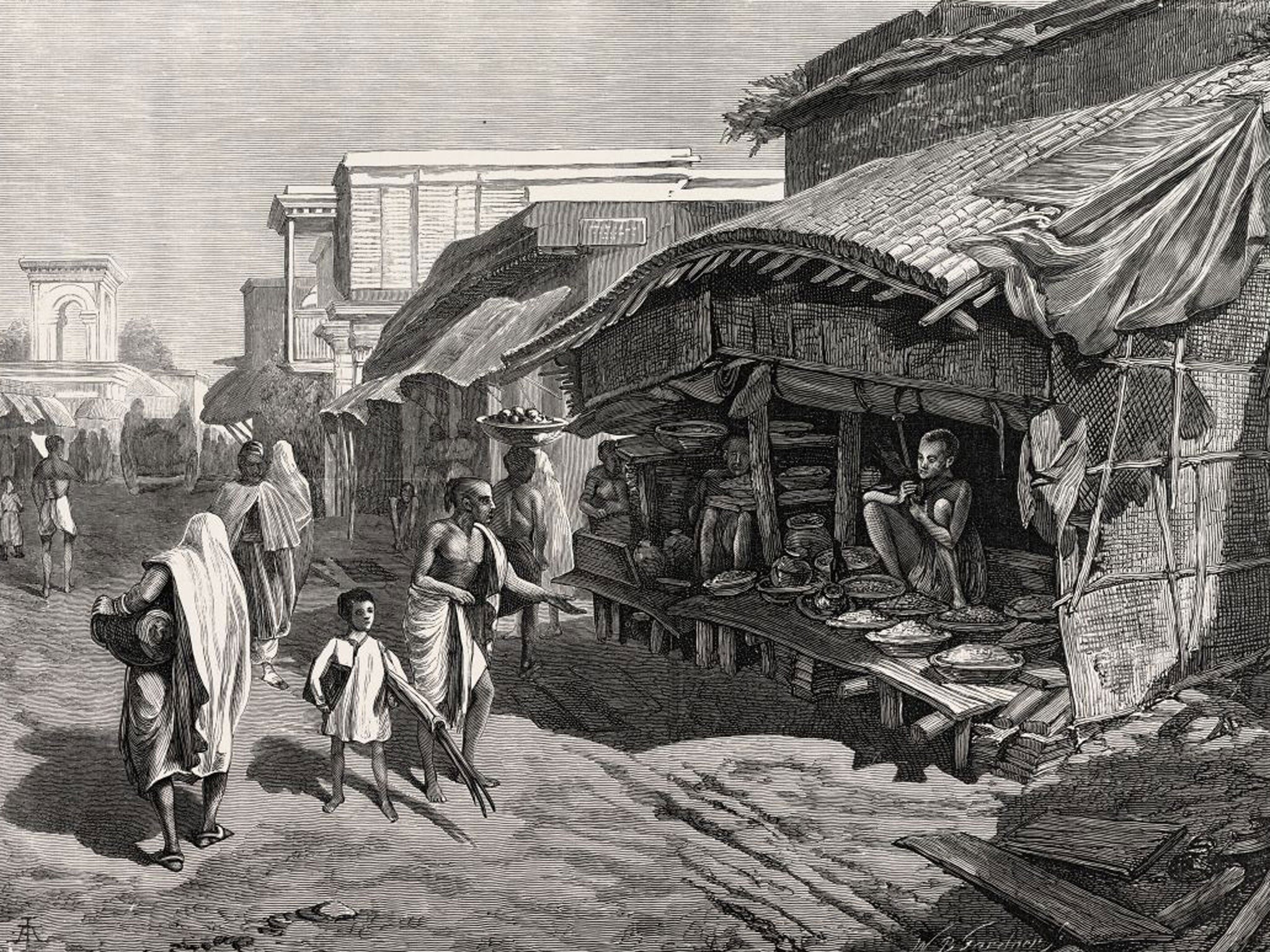

Your support makes all the difference.'Flood of Fire' brings Amitav Ghosh's Ibis Trilogy to a close and deals with events between 1839 and 1841 that led to the Opium wars, the British acquisition of Hong Kong and what the Chinese call the hundred years of humiliation. Fiction set against such a huge sweep of history can often be in danger of recreating the standard school lessons where, as the teacher drones on about how this happened and then this happened in a long recital of forgotten facts, most of the pupils are sent to sleep. It is a testimony to Ghosh's great skills that he can both teach us history and create believable fictional characters.

As the narrative moves from India to China, Ghosh vividly brings to life men and women who cope with the immense impact of the European empires of the 19th century: the undreamt-of opportunities to make money, the challenge to the customs and rituals of ancient societies and the creation of almost unbearable conflicts of loyalties.

Kesri, the farmer's son, who defied his father's wish that he should join the decaying Mughal army to enlist with the army of the new power in India, the British, helps his British masters defeat the Chinese, then realises that he is really a mercenary who can never experience the passion the Chinese feel as they defend their lands. Shireen Modi, the Parsi wife, makes a slow and unexpected realisation – that news her dead husband has sired an illegitimate half-Chinese child does not confine her to a living hell but can be a means of new, more liberating, life. And Zachary, born to a slave and her white master, who passes for white, soon learns that by echoing the arguments of his boss, Burnham, selling opium to the Chinese means bringing them the inestimable values of free trade and liberating them from their tyrannical rulers, he has an opportunity to make the sort of money the penniless American could never have dreamt about.

Zachary also provides Ghosh the chance to take on the mantle of Kipling and explore the adulterous world of the repressed British memsahibs. The setting here is Calcutta not Simla but Ghosh's description of the affair between Zachary and Mrs Burnham, which both wittily exposes the moral hypocrisy involved and provides a gripping denouncement, is a classic piece of writing .

What makes Ghosh's characters come alive all the more is the use of language. English is spiced with Indian words that the English in India incorporated in their everyday usage, Hindi, Bengali, even Chinese. The Indian novelists of the generation before Ghosh, like R K Narayan, would have felt obliged to provide a glossary. Ghosh, occasionally, translates, but often does not, yet pulls off this presentation of the medley of tongues his characters use with great aplomb.

Ghosh's novels have always explored the spin Europeans put on their empire-building that in acquiring other people lands, and subjugating them, they were not just motivated by profit but fulfilling a higher, selfless, moral mission to liberate and uplift these people from their wretched existence. It is part of his immense skill, both as a storyteller and his mastery of history (the novel's epilogue contains a list of books that could do justice to a doctoral thesis) that his narrative never remotely reads like a standard anti-colonial rant.

So far Ghosh's novels have dealt with the period when the European empires reached their zenith. It would be fascinating if he would now turn to the period when they passed into history. This is the one that more often excites British programme-makers and Ghosh could provide a much-needed perspective sorely missing from these narratives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments