Fall of Man in Wilmslow by David Lagercrantz; trans. George Goulding, book review

Lagercrantz's book is an amalgam of crime narrative, psychology and science

Who is David Lagercrantz? And should we care? The answer to the latter question is yes, as the Swedish author has taken on a massive publishing franchise, writing book four of the Millennium sequence with everybody's favourite Goth hacker Lisbeth Salander back in the pain business.

Inevitably, any writer with the temerity to take up the pen of the late Stieg Larsson (particularly with an unfinished fourth book by Larsson squirrelled away somewhere) is making themselves a hostage to fortune. Initially, Lagercrantz seems a surprising choice, given that his book about a footballer, I Am Zlatan Ibrahimović, seems a million miles away from Nordic noir – except that it shares the genre's keen social concerns. Scandinavian crime aficionados are already in a feverish state (both pro and con) over the forthcoming book. However, before the appearance of The Girl in the Spider's Web, we now have a chance to assess Lagercrantz's skill in something closer to the crime field with his novel Fall of Man in Wilmslow – and a very curious hybrid it is, though a winning one.

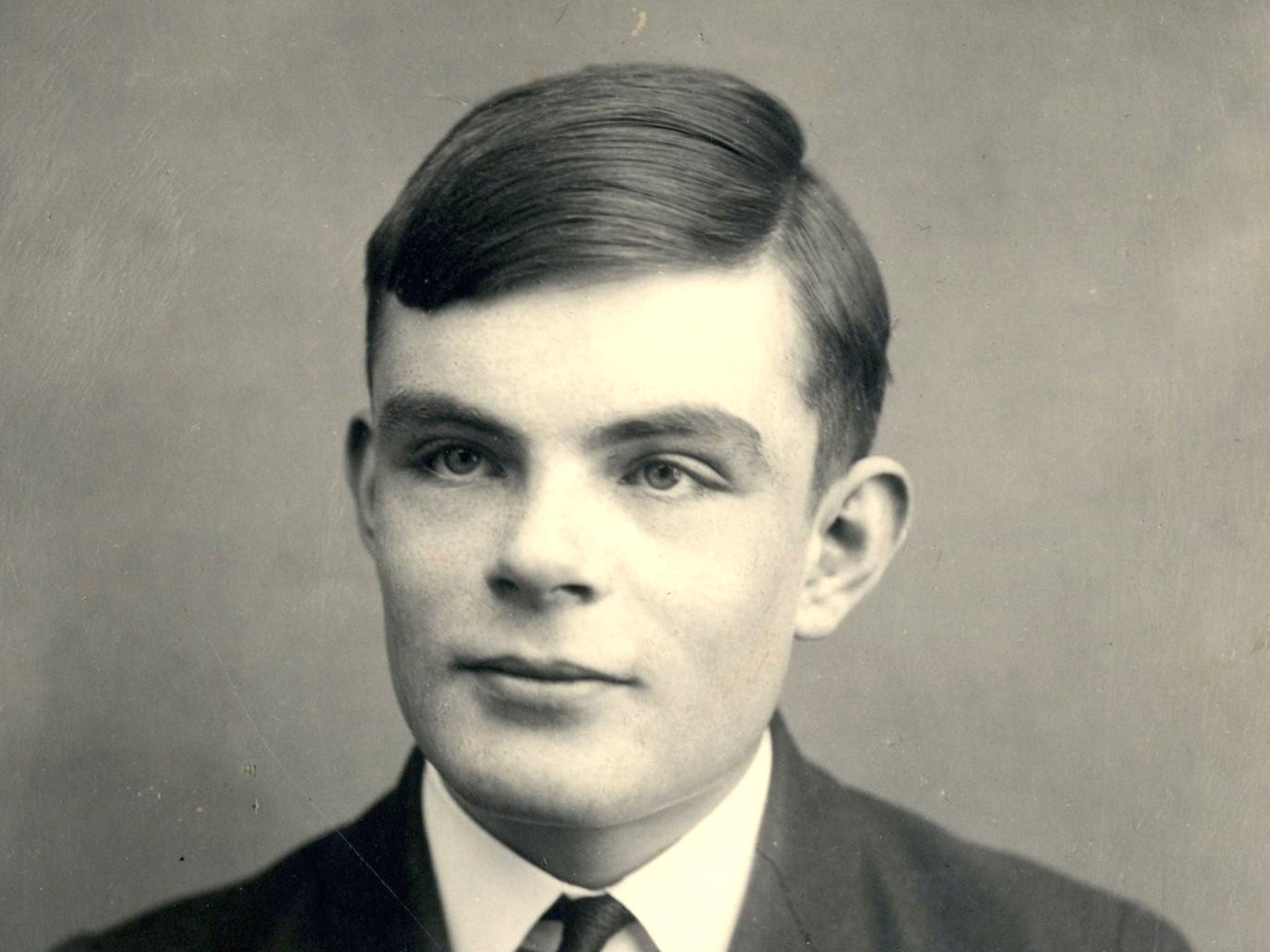

This is an amalgam of crime narrative, psychology and science; the strapline reads 'The Death and Life of Alan Turing'. Lagercrantz channels a topical interest in the mathematician who helped crack the Enigma code in a novel set in 1954, beginning with Turing found dead at his house in Wilmslow. He appears to have created his own unusual method of suicide: a poisoned apple. Assigned to the case, Detective Leonard Correll learns that Turing has been convicted of homosexual offences (in reality, Turing was forced by the judiciary into chemical castration because of his sexuality – he was retrospectively exonerated by Gordon Brown).

The verdict of suicide is complicated by the veil of secrecy drawn over the mathematician's war record, and the security services have decided that Turing's illegal sexuality might have made him a target for Soviet spies. But as Correll gets closer to the top-secret work at Bletchley, he finds himself the target of the same individuals who destroyed the dead man.

As a Swedish writer attempting to capture an English idiom for this most English of subjects, Lagercrantz shows undoubted chutzpah, but he unerringly finds the correct phrasing (although we do not know what finessing translator George Goulding has wrought). Perhaps the most signal achievement here is the clever melding of two narrative forms: a sympathetic biography of a real historical figure treated appallingly by the establishment, and a police procedural in which a dogged copper tries to crack a mystery in the teeth of bloody-minded intransigence.

Inevitably, the sections on the detective's own tangled psychology cannot exert the fascination of the dead mathematician. But what really energises Lagercrantz is his passionate distaste for those who brought down Turing – when we hear praise in the book from English authorities for Senator McCarthy's attacks on communists and homosexuals, we know exactly what to think of them. And Lagercrantz is perceptive in his treatment of the tragic Turing. What he does not do is give us is an idea of how he will wear Larsson's mantle. We'll just have to wait and see how successfully he does that.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments