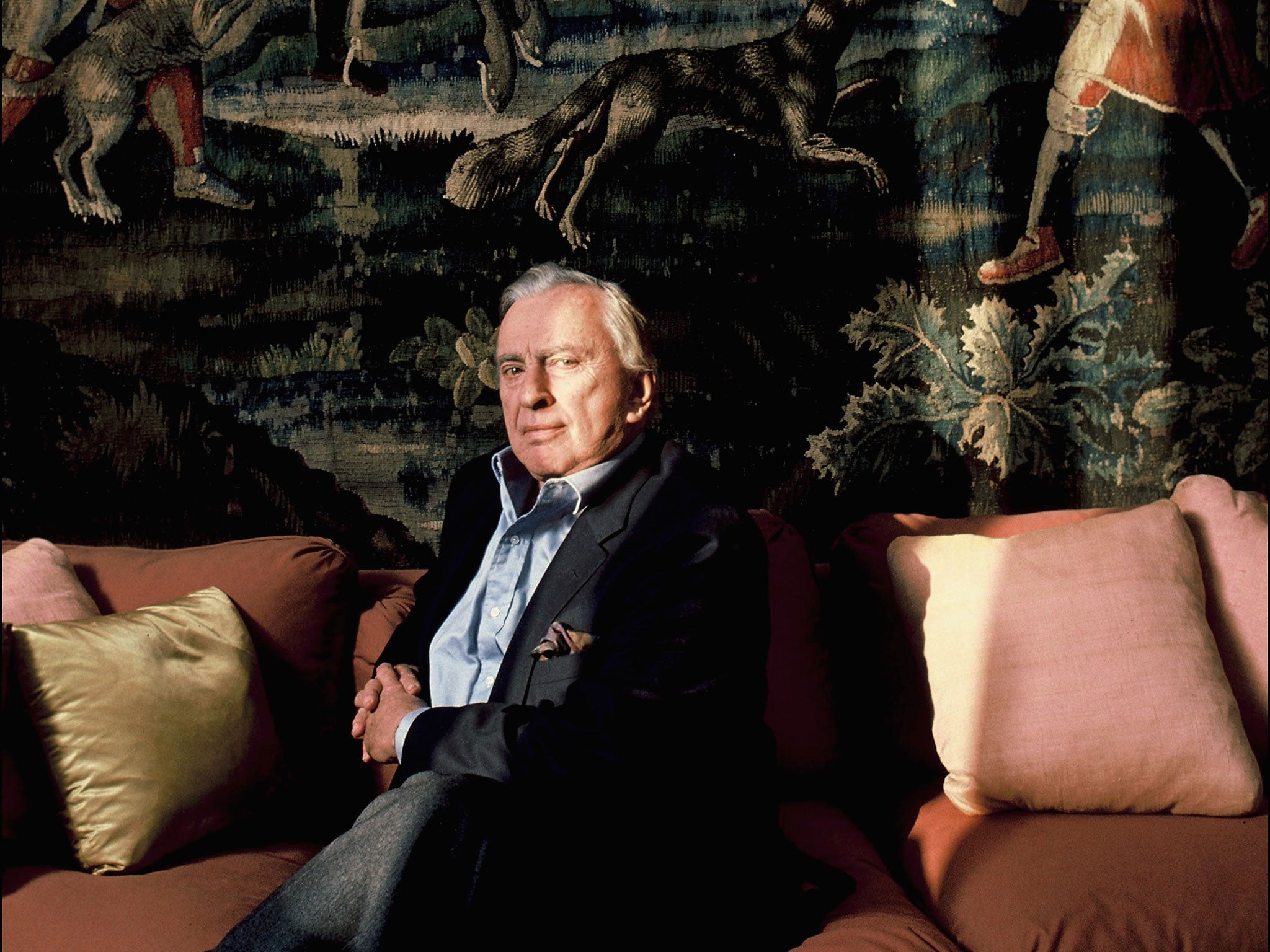

Every Time A Friend Succeeds, Something Inside Me Dies: The Life of Gore Vidal by Jay Parini, book review

Biography of Gore Vidal shows the private side of a mercurial 20th-century titan, writes James Attlee

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three years after Gore Vidal's death it is already difficult, particularly on this side of the Atlantic, to grasp quite what a dominant position he once occupied in American culture, simply because that culture has changed beyond recognition.

Public intellectuals of his stature have largely disappeared, replaced by celebrities, while the broadcast media has fragmented into thousands of channels, losing access to the vast audiences it once held spellbound. Jay Parini first met Vidal while on the kind of sabbatical mere mortals only dream of. Above the villa he shared with his family near Ravello, on Italy's spectacular Amalfi coast, loomed another – "massive… alabaster-white, clinging to the rocks like a swallow's nest" – with spectacular views across the bay. Did it belong to a nobleman, or a mafia don? No, the local tobacconist tells him, "Lo scrittore! Gore Vidal. Americano."

From his study in this house, lined with framed magazine covers bearing his own profile – "when I come into this room in the morning to work I like to be reminded who I am," he told Parini – Vidal chronicled, provoked and satirised the country of his birth, a nation to which he was bound by ties neither distance nor political disaffection could break.

The friendship begun at Ravello lasted until the older writer's death in 2012, sustained by means of extended international phone-calls, often begun with the question from Vidal: "What are they saying about me?"

"It would be fair to say", Parini admits, "I was looking for a father, and he seemed in search of a son." Not, perhaps, the ideal relationship on which to base a biography. Fortunately, when the inevitable request to write one came, Parini's wife (a psychologist) insisted he refuse while its subject was still alive. Instead, Parini promised to write his book after Vidal's death. Vidal relished the Boswellian overtones of this arrangement, taking to punctuating his more brilliant sallies with the remark, "I hope you are writing this down!" "In fact", Parini tells us, deadpan, "I did."

Building on the access his intimate friendship granted him, Parini is in a unique position to unpick the complexities and contradictions that make up this most mercurial of characters. He does so by tracing the course of Vidal's life chronologically, from his privileged but dysfunctional family background in Washington DC to his eventual identity as an international literary figure in the mould of Mark Twain or Henry James.

This somewhat conventional structure is enlivened by the insertion of brief vignettes between chapters from Parini's store of personal memories, which often reveal Vidal at his most vulnerable, caustic or hilarious. The fact that he was a "star-fucker", in his friend Leonard Bernstein's memorable phrase, that he maintained friendships (as well as bitter enmities) with everyone from Hollywood stars to diplomats, from film directors, novelists, playwrights and politicians to poets and pimps, and that he introduced Parini to many of them, means he is reflected back to us in their recollections. One example is the beautiful description by Stephen Spender of the young writer in Rome: "He had tawny hair and eyes that made me think of bees' abdomens drenched in pollen. The centre of each eye, perhaps its iris, held a sting."

At his best, as Christopher Hitchens wrote elsewhere, Vidal shared with Oscar Wilde the rare gift "of being amusing about serious things as well as serious about amusing ones"; at his worst, as Parini admits, "he could be cantankerous, testy, ill-mannered, a terrible snob, a drunken bore", someone who "could feel an insult from a thousand miles away" and never forget it.

Vidal's literary activities were various. "I am a novelist turned temporary adventurer," he explained, "and I choose to write television, movies and plays for much the same reason that Henry Morgan selected The Spanish Main for his peculiar – and not dissimilar – sphere of operations." In other words, he needed the money in order to finance the lifestyle – and the houses – he felt he deserved. Astonishingly prolific, he was the author of some 22 novels under his own name, along with potboilers written under pseudonyms. The City and the Pillar, published when he was only 23 years old, was the first American novel to deal openly with homosexual themes. Some 20 years later, his satirical novel Myra Breckinridge (1968) was another first for the American reading public, featuring a transgender heroine: riding the wave of the Sixties sexual revolution, the paperback sold two million copies within a month of publication and was translated into 15 languages.

Frustrated in his own political ambitions, he resolved to write about power rather than pursue it, tapping into post-war America's desire to understand itself. Almost single-handedly he revived the historical novel, becoming the semi-official biographer of the American Republic with his seven-novel series, Narratives of Empire. Others, such as Julian, explored political machinations against the backdrop of the classical world. While his output was prodigious, his hit-rate was erratic; as many of his plays and novels were complete failures as wild successes. It is his perceptive and acute essays that are seen by many critics (including Parini) as his most lasting contribution to American literature, something that would doubtless have irritated him.

Vidal gained his passionate attachment to democratic traditions as a child, acting as the eyes of his blind grandfather, a US senator, accompanying him to work and taking a masterclass there in oratory and showmanship that would serve him well. In his view America had declined from a democracy into "a sort of militarised republic", a slave to its ballooning military budget, which could only be justified by the conjuring of imaginary foes. His loathing of the Kennedy clan (he fell out with Bobby) was only exceeded by his visceral hatred of Ronald Reagan and of William F Buckley Jr, the owner of conservative magazine The National Review with whom he famously clashed in a series of television debates in 1968.

In one appearance he goaded Buckley relentlessly until the latter's mask slipped and he called Vidal "a queer" on air and threatened to smash his face in. Another of Vidal's big-beast rivals, the novelist Norman Mailer, did punch him in the face at a socialite party in New York. On that occasion Vidal stepped back, dabbed his mouth and said, with immaculate timing, "Norman, once again words have failed you"."

Writer, pundit, bon viveur, frequenter of chat-show couches, Vidal will be remembered by his contemporaries, Parini is sure, "as a meteor who streaked through the night skies, with a fantail of sparks". He is less certain about future generations. "Will they read him? It's impossible to know." With this fine biography, he has done his part in ensuring they will.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments