Euphoria by Lily King, book review: Tribal loyalties and a tragic love story

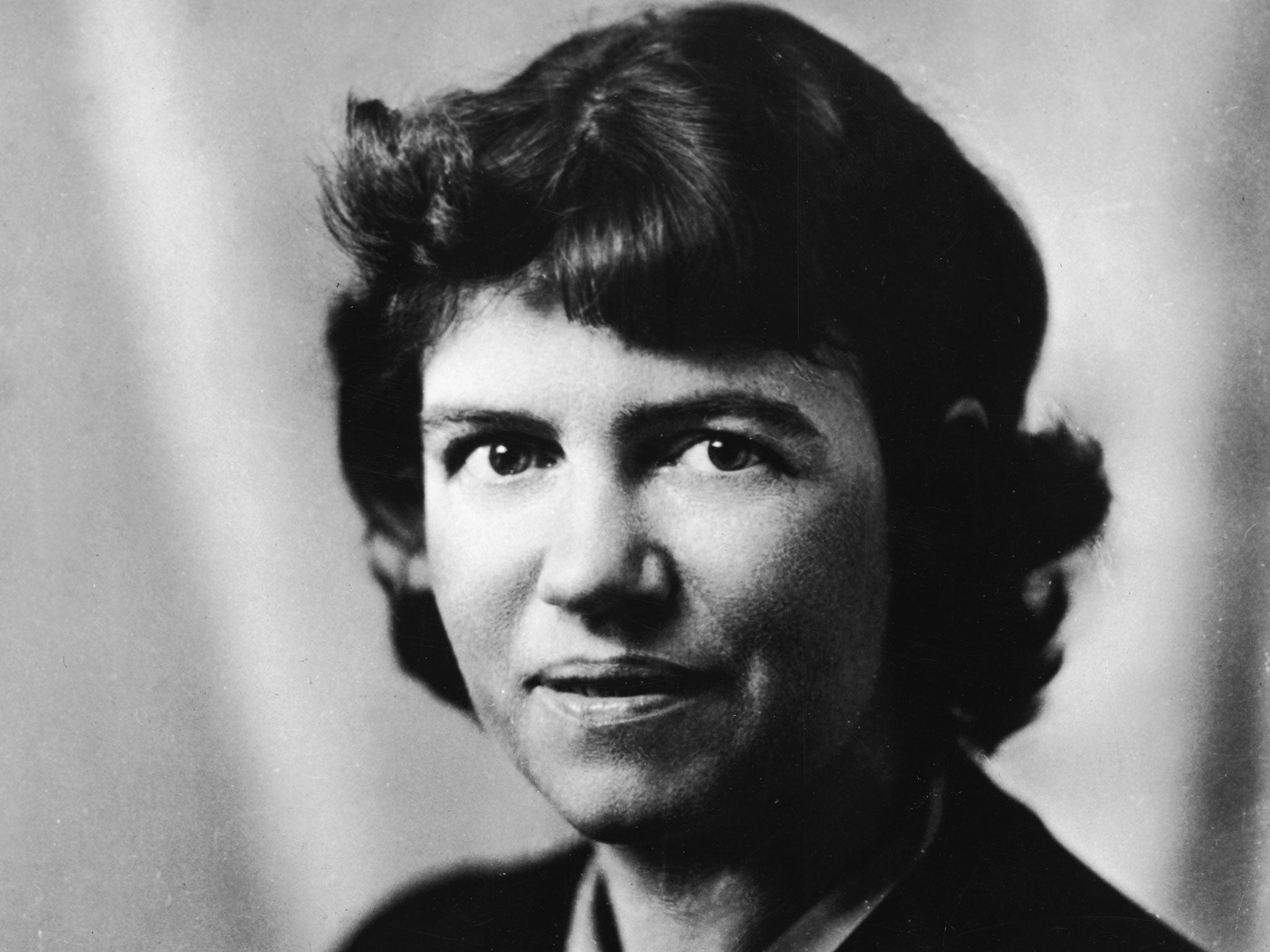

A sensual novel based on the life of the American anthropologist Margaret Mead

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.American anthropologist Margaret Mead, whose career took off in the 1920s with the publication of a groundbreaking work on Samoan adolescence, is not, at first glance, the most zeitgeisty subject for a novel. Yet Lily King, by homing in on an intense emotional period of Mead's life and turning it into fiction, has made her newly relevant.

King takes the basic facts –Mead's 1933 fieldwork with her New Zealander second husband among the tribes of the Sepik River in what is now Papua New Guinea, and their brief association with fellow anthropologist (and Mead's soon-to-be third husband), Englishman Gregory Bateson. What emerges, in heady, cultivated prose, is both the love triangle that develops and the high-handed primitivism of Western anthropology's pioneers. Nell Stone is a Columbia-schooled intellectual, married for two years to Australian alpha-male Schuyler Fenwick (Fen). The novel begins with their abrupt departure from an extended stay with the Mumbanyo tribe.

Later it transpires that this takes place at Nell's insistence; unsettled by her recent miscarriage and the Mumbanyo's violent rituals. It is Christmas Eve; the couple joins a boat replete with drunken revellers, the women's "eyelashes like black ferns" starkly contrasting with the anthropologists' "dirty duffels and malarial eyes". Nell has broken glasses and a broken ankle, caused by the irascible Fen, an unreconstructed bully jealous of her success. The pair had planned to go on to Australia and work with indigenous settlements but an encounter that night with Andrew Bankson, known to them only by reputation, determines a different path. Bankson introduces Nell and Fen to the Tam, another tribe along the Sepik River; they decide to live among them, having first rejected more inferior candidates lacking the Tam's attractive beach and "advanced" art.

King subtly ridicules these less-than-principled attitudes; echoed in Bankson's earlier preposterous disappointment with "an impossible tribe who refused to tell me anything until I learned their language and when I had learned their language still refused to tell me". This belies, however, the serious intent of all three anthropologists. Bankson has come to New Guinea to escape the reach of the widowed mother on whom he is financially dependent. His meeting with Nell and Fen follows a botched suicide attempt. He and Nell bond over similar familial losses, though Bankson's overwroughtness and musings on his Cambridge origins provide the weakest aspects of the novel. Fortunately, Nell's diary intersperses with his narrative, giving vivid accounts of real discoveries and breakthroughs. Each page of the book permeates with a ripening sensuality, a blend of tropical heat, tension, and – crucially – the observation at close range of a culture where mutual sexual satisfaction is key.

Nell and Fen are immersive in their approach to tribal society: Nell empathically, Fen by sheer opportunism. While she rigorously records every interaction with the Tam, Fen seizes the chance to steal an important artefact, with devastating results. Kings's writing is soaring, rapturous. While it raises uncomfortable moral questions that recall Ann Patchett's Conradesque State of Wonder, it holds the fatalism of the tragic love story, of history closing in. For Nell: "always in her mind there had been the belief that somewhere on earth there would be a better place to live, and she would find it". Less than a decade later, her imagined paradise will be occupied by Japanese forces in a world at war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments