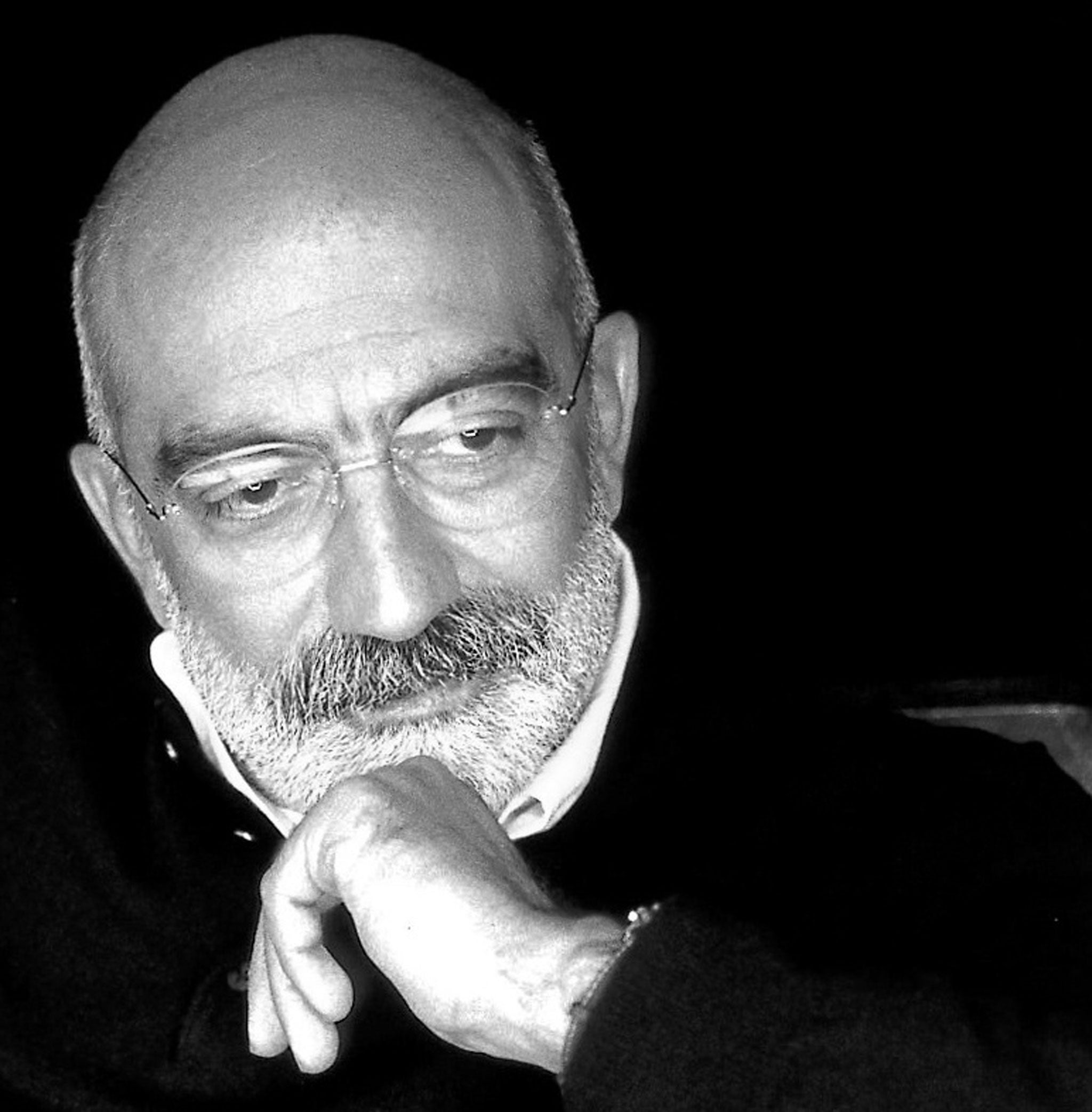

Endgame by Ahmet Altan; Trans. Alexander Dawe, book review: This really is the big sleep

This isn't the best book with which to introduce Altan to readers in English

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ahmet Altan's "existential thriller" opens with a man sitting on a bench at night in a small Turkish town. He is a crime novelist, and came to this out-of-the-way place to write, but instead of working, he has become entangled in the town's intrigues and has ended up a killer, the fatal shot fired only moments before.

Now he sits and takes account of himself, and of his role as a character in the greater novel written by God, with whom, naturally, he can't help comparing himself: "A good novelist doesn't build on coincidence, or stoop to coincidence to get out of a corner. But God has a savage sense of humour. And coincidence is his favourite joke. And life is nothing but a string of coincidences."

You might argue that this small town is too small for coincidences. It didn't take long for the (nameless) narrator to find the local crime bosses sauntering over to his café table to sound him out, and not much longer for him to start sleeping with their women – primarily the beautiful and mysterious Zuhal, the on-off girlfriend of Mustafa, the deeply corrupt town mayor, but also the older, voluptuous Kamile, wife of a rival family boss, who turns up to his house with the offer of home-cooked sweets and sweaty, hungry sex.

He's also not beyond eyeing up his housekeeper and having regular sessions with the local prostitute, who puts out for free on occasion, but invites herself over for a full-price bout when she's short of money, and with whom our tough but sensitive hero is often happy just to chat, either philosophy or the intricate pillow talk of the town. Truly he is that cliché: a writer with a heart of gold.

You'd think he was causing enough upset to send the town off the rails all by himself, but in fact the motor of the plot is an abandoned church which apparently hides treasure, which everyone suspects everyone else of secretly trying to find.

As Mustafa tells our man, "Outsiders don't get that. Whatever it is that makes a man a man, well it's the same in that this treasure makes this town. It's the centre of power. And power is never shared. If it is, well then it isn't power."

This isn't a plot-heavy book – that's the "existential" aspect, I suppose – but unfortunately this also leads to long repetitive passages of dialogue, longer ones of writerly rumination, and pages full of text messages between Zuhal and the writer-lover-killer that are eminently skimmable, if not skippable: "We have to decide if we're going to live in reality or stay in the world of dreams… isn't condemning one thing to the world of dreams the same as being a prisoner of your own dreams?" Yes, yes. Whatever you say about God's reliance on coincidence, his dialogue is better than this.

Altan is an important figure as a journalist and writer in Turkey, where he has been fired as the former for writing about "the Kurdish problem" and censored as the latter for his sexual content, but this doesn't seem like the best book with which to introduce him to readers in English. Its politics is local, and won't help a foreigner understand the deeper workings of the country, and while the sexual intrigue does carry across, I can't help thinking how Georges Simenon would have rattled off this kind of story in 150 pages. At more than twice that length, Endgame drags.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments