Electric Shock: From the Gramophone to the iPhone: 125 Years of Pop Music by Peter Doggett, book review

Have we passed 'peak pop'? This mammoth study suggests the era of digital plenty has erased music's historical perspective, writes DJ Taylor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Reaching the closing stretches of It's Too Late to Die Young Now (2014), his entertaining memoir of life as a music journalist on the 1990s-era Melody Maker, Andrew Mueller files the not wholly unheralded judgement that rock and roll has, as he idiomatically declares, "pretty much had it". There will still be great bands; there will still be good music; but a long, hard look at the evidence suggests that since the decade-and-a-half from 1954 to 1969, book-ended by Bill Haley's "Rock Around the Clock" and Jimi Hendrix's Electric Ladyland "everybody has just been playing dress-up".

And what would Peter Doggett, the author of this gargantuan 700-page history of electrified music (starting point: the birth of recorded sound) make of Mueller's lament? Certainly, Doggett's brief is wider, nothing less than all popular music, rather than the stylised 12-bar racket that began to pulse out from the American South in the early 1950s, but there is still a terrific sense of disillusionment; talk of a world in which music is less important than the technology which delivers it; above all, a feeling of well-nigh metaphysical disquiet brought about by a generation of consumers who, in an age of streaming and downloads, take their aural pleasures for granted.

For Doggett, who started listening to pop back in the frugal and vinyl-bound 1960s, one of those "who grew up owning a handful of records, replaying them endlessly until we had saved up enough money to purchase another", today's young people seem "like kids let loose in Hamley's toy warehouse, with the freedom of taking everything home at the end of the day." With this freedom, Doggett argues, "has come a loss of perspective that can be both chilling and exhilarating", a music that exists outside history, where nothing is connected and everything, in a landscape unregulated by the taste-brokers of an all-but-vanished music press, is equally valid, or not.

Part of the problem, he acknowledges, is the breakneck pace of music's evolution when compared with rival pursuits. The novel, for example, took upwards of a century and a half to get from Fielding's picaresques to Joyce's interior monologues, whereas the journey from early Motown to the portals of hip-hop lasted barely a couple of decades. If, as he notes, "every art form has a limited lifespan, and a moment when it will simply not allow for any further experimentation or novelty", then the threat of obsolescence hanging over so short-term a phenomenon as pop is greater still, requiring constant infusions of new blood and stylistic trickery.

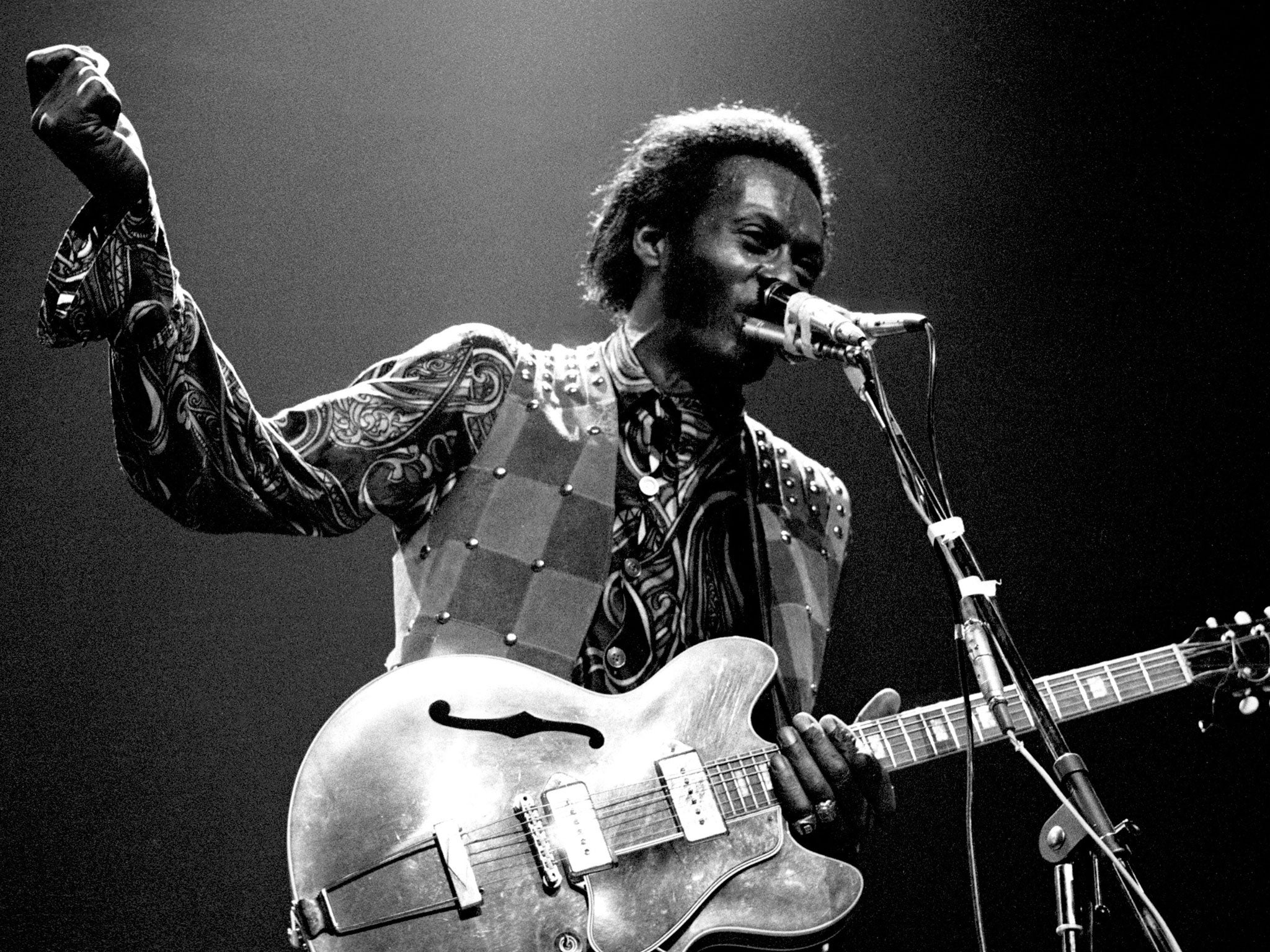

Evanescence, naturally, is the historian's nightmare, and the great virtue of Electric Shock's early sections is Doggett's determination to chart the precise development of his various contending forms – ragtime, jazz, swing and so on – and the hybridised mutants into which they swiftly morphed. This approach reaches a conceptual highpoint when he comes to the birth of rock and roll, here identified as the projection, by performers as various as Chuck Berry, Elvis and Bill Haley, of a melange of styles in which black rhythm and blues, 1940s swing and speeded up country music all played a part and nearly everyone involved imagined that they were coming to the proceedings from a slightly different angle.

As the story rushes on, from surf music to girl groups, from Sixties protest songs to the Beatles, heavy metal and prog rock, several general conclusions present themselves. One is the absence of autonomy: all pop music plagiarises existing material, and the doughtiest old Delta bluesman was quite as likely to have stolen his licks as a studio-bound producer of the early 2000s. Another is the blanket disapproval shown by all parental generations to the next big thing. A third is the "revolt into style", to borrow Thom Gunn's phrase, whereby anything remotely challenging or rebellious is immediately picked up, quietened down and commercialised by the music industry, and today's expletive-toting rapper is tomorrow's tycoon.

A fourth conclusion, inevitably, takes in the listeners. Most consumers of popular music, Doggett assures us, like tunes they can whistle, are more interested in the tunes themselves than the people who sing them, and, once they have whistled them to death, cheerfully move on. All this means that the real history of popular music is more or less unwritten – never more so than in the 1960s when, for all the fuss made by trend-surfers about, let us say, the Stones and the Kinks, two of the decade's best-selling albums were the soundtracks to Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music.

The key period, for Doggett as with Mueller, is 1965-68, a time of extraordinary innovation, followed by the rise of "art pop" determined to detach its own elite audience from the public at large.

None of this, alas, is good news for the "serious" music fan bent on evaluation and discrimination, and you sense that Doggett finds some of the positions he defends very difficult to live with: his innermost soul just itches to yell at the reader that Prefab Sprout, as it may be, are "better" than the Stone Roses or that Simon Cowell has done more to ruin music than the MP3. Meanwhile, the few weaknesses of this altogether heroic endeavour are entirely incidental. They include a curious distaste for the old-style NME (of whose 1970s incarnation he remarks that it "reinvented itself as the hippest of all the British rock papers, filling its pages with refugees from the ailing underground press and clichés borrowed from its American equivalents".)

There is another book to be assembled on the back of Electric Shock, demanding whether, in an age of mass-market impositions, such a thing as a genuinely "popular" music even exists, and Doggett is just the man to write it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments