Deep Down Dark by Hector Tobar, book review: Trapped in a hell under earth as the Chilean mining disaster is revisited

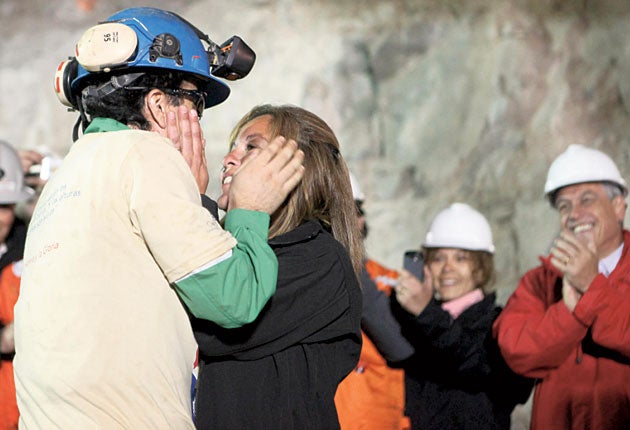

Yes, I cried when the miners were reunited with their families, and so will you, but Tobar does more than rehash the media’s feel-good story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 5 august 2010, Carlos Mamani had the first day from hell.

He didn’t arrive late, or dress inappropriately, but the young Bolivian had been working underground at San José mine, in northern Chile, for a few hours when an explosion left him, and 32 colleagues, trapped 700 metres below the surface of the Atacama desert. Some of the miners were apprentices, others veterans, and a few had even survived previous accidents. All considered copper mining a dangerous occupation which would eventually earn them money to improve their families’ lots. What nobody anticipated was that they would remain underground for 69 days and that their rescue would captivate the world.

The story of “Los 33” speaks to universal anxieties about darkness, isolation, death. Perhaps it also seems strange to British readers, following the demise of our mining industry, that men still labour in perilous underground corridors. San José was dubbed “hell” by miners and Héctor Tobar, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, who has interviewed everybody involved, writes: “[It was] known for its primitive working conditions and perfunctory safety practices.” The mine’s owners, Marcelo Kemeny and Alejandro Bohn, were “gambling with the miners’ lives”. Following the explosion, they waited five hours before informing the authorities, then shunned miners’ relatives who set up camp outside San José to anxiously await news.

Rescuers’ drills reach them after 17 days but another 52 pass before they’re carried to safety in a specially designed lift. Tobar’s challenge is to make his book compelling at the same time as reflecting the miners’ predicament. Recounting events in the present tense, he builds tension and dramatises subplots below and above ground. However, he repeats details, perhaps because he distrusts readers’ memories or wants us to share some of the miners’ boredom. Occasionally, he gets carried away and romanticises the miners’ women: “Her daily vigil on behalf of her cheating but now caged ex-husband, is a kind of love poem.”

Reading Deep Down Dark, I inevitably wondered how I would cope with 69 days underground. Yes, I cried when the miners were reunited with their families, and so will you, but Tobar does more than rehash the media’s feel-good story. The mine owners haven’t been held responsible and the miners have struggled to readjust to everyday life: “The man who came out of the mine isn’t the same one who went in.” President Sebastián Piñera believes the miners symbolise their “nation’s fortitude” but it’s worth remembering that, in the desert near San José, “the disappeared” victims of General Pinochet’s regime are believed to be buried. For some Chileans, the agonising search for loved-ones goes on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments