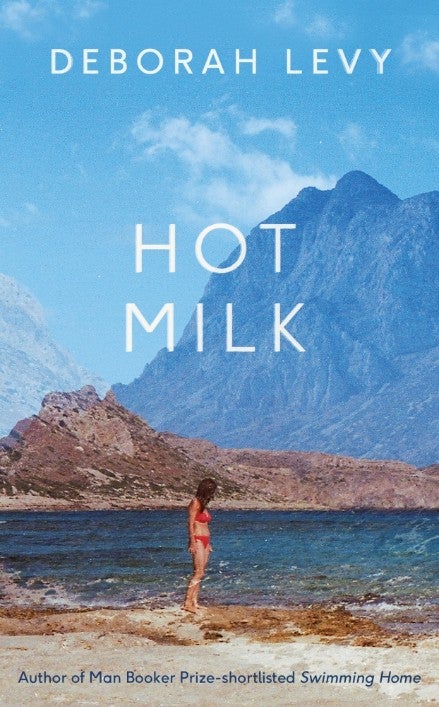

Deborah Levy, Hot Milk: 'Perfectly crafted portrait of a relationship in crisis', book review

The story opens with Sofia on the beach suffering from a sting from a jellyfish called the Medusa, and an atmosphere of threat from a snake-headed female resonates from the first page

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The mother-daughter relationship is famous for being monstrously fraught and Levy’s dreamlike novel Hot Milk makes uncomfortable reading – despite exquisite prose – because it takes us deep into the swampy terrain of a mother’s love and despair, a daughter’s dependency, and the hostility and rage that arises between two individuals battling for their lives.

Sofia is a half-Greek, half-English 25-year-old visiting a clinic in Almeria, Spain, with her mother to try to find a cure for her mother’s ever-changing, elusive maladies. The story opens with Sofia on the beach suffering from a sting from a jellyfish called the Medusa, and an atmosphere of threat from a snake-headed female resonates from the first page.

Sofia is an anthropologist who has been forced to sacrifice her own dreams, work as a waitress, and care for her mother. She is clear in her yearning if lost in all other ways: she wants a “bigger life”. When asked her occupation she replies: “I don’t so much have an occupation as a preoccupation, which is my mother, Rose.” She is forever propping up her limping mother, physically carrying around the burden of her.

The Mediterranean-born myth of Demeter and Persephone infuses Hot Milk, from the setting – sweltering Almeria and Athens – to the oscillations made by mother and daughter as they continually exchange the roles of victim and abuser, powerful and weak. Rose’s medical symptoms are enigmatic, probably invented, and she flits between being weak, needy, coquettish and manipulative. Sofia struggles to breathe near her, looks for exits, air. The novel asks: why is it that mothers must rage and go to extreme lengths to stop daughters leaving?

Economics – personal, national and international – provide a tangible anchor to the literal and metaphysical Greek psycho-drama. Rose has mortgaged her house to pay for the clinic; Sofia’s father funds another family while neglecting to contribute to Sofia’s life; Sofia constantly worries about money; talk of the Euro and austerity place the story within a very contemporary context.

Alongside all of this, there is desire. Sex suffuses the novel, with pleasure frequently crossing into pain. There are sunburn, blisters, cracked lips and stings, skin in the heat and transgressions into lust. Just as Sofia is non-committal and drifting in life, she floats in a passive manner among sexual partners, propelled not so much by emotion as by a desperate attempt to escape being crushed under the weight of her mother’s irrational demands. She is perpetually trying to be bolder.

There is much gender-blurring, with women looking like men, and this boundary-crossing provides the back-drop for the tremendous struggle at the heart of the novel. Hot Milk is perfectly crafted, a dream-narrative so mesmerising that reading it is to be under a spell. Reaching the end is like finding a piece of glass on the beach, shaped into a sphere by the sea, that can be held up and looked into like a glass-eye and kept, in secret, to be looked at again and again.

Suzanne Joinson’s second novel ‘The Photographer’s Wife’ will be published by Bloomsbury in May

Hot Milk, by Deborah Levy. Hamish Hamilton £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments