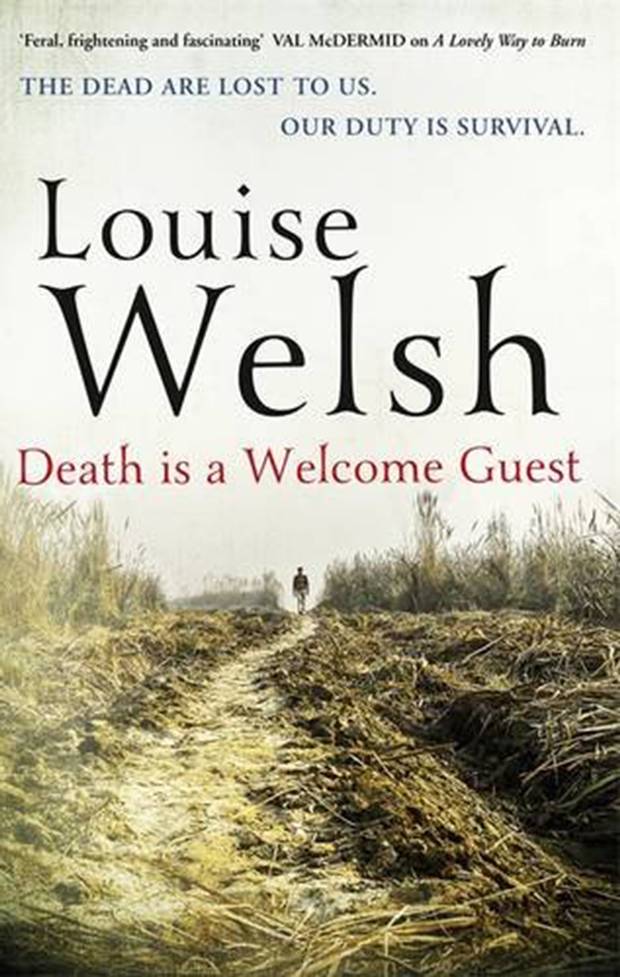

Death is a Welcome Guest, by Louise Welsh - book review: A stand-up survivor

Hodder and Stoughton - £12.99

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Death is a Welcome Guest is the second part of Louise Welsh’s already impressive “Plague Times” trilogy. Episode one was an offbeat, unsettling tale starring Stevie Flint, a love-sick TV product demonstrator turned credible dystopian heroine. My disappointment at Flint’s absence here is really a testament to the gothic brilliance of Welsh’s opening salvo.

In her stead we have Magnus McFall, a capable Scottish stand-up. Quite what Welsh has against light entertainment intrigues. First QVC, now an undivine comedian caught in infernal events. As ideas of guilt and innocence swirl, one assumes that the name McFall is McSignificant.

First, there’s a chilling prologue that could put P&O out of business: a cruise liner is struck by “The Sweats”, the pandemic reducing humanity by the million. Welsh’s genius for giving you the willies contrasts the “picture postcard of luxury” with “the stench of decay awaiting the medics in the lower decks; the impossibility of salvation.” This terse phrase haunts what is to come.

Hints of McFall’s post-lapsarian fate snake through the opening chapters. He witnesses a plague victim swoon under a tube train, snorts coke with Johnny Drongo, the comic de jour, who promptly headbutts him. Somewhat conveniently disoriented, McFall intervenes in an attempted rape, and is sent to a “Sweats-soaked” Pentonville.

He escapes with fellow alleged “nonce”, Jeb, their mutual distrust generating considerable tension. What exactly has Jeb done? Will the “innocent” Magnus be branded as a criminal in the newly Old Testament England? The sheer strangeness of a de-populated London insinuates itself when the pair find shelter from the storm in a deserted luxury hotel.

Death is a Welcome Guest expands the canvas of its predecessor, but employs even more muted and melancholy tones. Social and political possibilities abound in “a new world where the only rank was survival”. This bare necessity denies Magnus a present or a future, and so he falls back on his past on Orkney, weighing the deaths of his father and cousin against the millions perishing now. Welsh’s quest narrative echoes everything from Arthurian romance to Sarah Perry’s wonderfully uncanny After Me Comes the Flood. In both novels, slippery questions of identity rub sticks with religion and sexuality. For Welsh, the resulting sparks illuminate uneasy ideas of justice, morality and sacrifice. I have no idea where part three is heading, but I cannot wait to find out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments