Cleopatra: A Life, By Stacy Schiff<br />Antony and Cleopatra, By Adrian Goldsworthy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

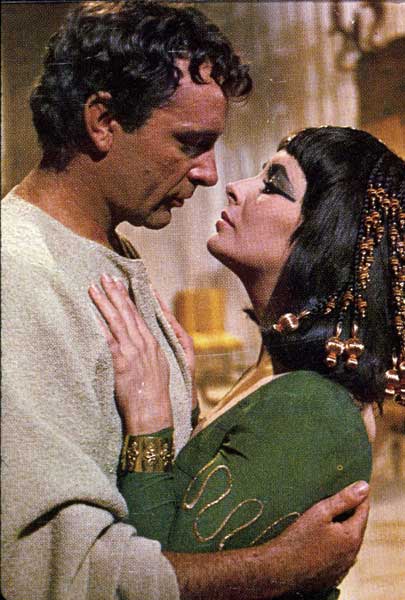

Your support makes all the difference.They were the couple from hell – he a drunken, idle and sadistic bruiser, she mutton dressed as lamb, and murderous with it. And yet, by some odd alchemy the story of Antony and Cleopatra has been transmuted into the gold of romance. The title of Dryden's tragedy about them, All for Love, or the World Well Lost, says it all. Love trumps power.

Both of them, the bloodstained Triumvir and the Queen of Egypt, a serial killer whose brothers and sisters were her special subject, would have laughed the idea out of court, for power was all they were really interested in. No doubt they were fond of one another, but their partnership was fundamentally political, even if it offered the bonus of expressing itself sexually; they were, so to speak, the Clintons of the ancient world.

Mark Antony came from a good family, but he misspent his youth and for a time was a young nobleman's kept boy. He ran up huge debts and came to the attention of Julius Caesar, who settled them in return for political services rendered.

During the civil war which his patron eventually won, Antony provided convincing evidence of administrative incompetence. He was a brave soldier but no great tactician. In a long military career he only won a single set-piece battle. He had an unquenchable appetite for sex and alcohol, and a slightly surprising taste for domineering women. Bluff and down-to-earth in his manner, he appeared to be loyal to his master; but there was a touch of the Iago about him. Forewarned of the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar, he omitted to pass the information on.

Antony counted on being Caesar's political heir, but when the dead dictator's adopted son, the teenaged Octavian, arrived on the scene, he had no alternative but to give ground. They entered into an unwilling alliance and carved up the empire between them. Antony took the eastern half. This included Cleopatra, previously Caesar's mistress, and he stepped unhesitatingly into his great predecessor's bedroom slippers.

Eventually they both went down to defeat in a war with the cool and collected Octavian. What their long-term aims were is hard to say. Some have suggested, fancifully, that they meant to replace Rome with Alexandria as the headquarters of empire. In truth, they had no joint plan. Strategic thinking was not Antony's forte, and he probably saw himself simply as a successful Roman politician. As for the Queen, her only ambition was to restore her kingdom's lost glories.

A modern scholar once claimed that Cleopatra ranks with Hannibal among Rome's most dangerous enemies. Hardly; she was never remotely in a position to be a serious threat. A Macedonian Greek, she was the daughter of the absurd Ptolemy XII "Auletes" (the nickname means flute-player, and probably also fellator – in other words, it was an ancient term for playing the pink oboe).

Cleopatra was the first of the Ptolemaic pharaohs to learn Egyptian, but she followed their practice of using Egypt as a cash cow. Although no great beauty, she was endowed with charm, intelligence and a talent to amuse. Threatened by the superpower of the age, she defended her country's independence by making herself indispensable, personally as well as politically, in quick succession to two of Rome's leading men. This brought immediate dividends, but for a state to base its policy on the careers, indeed the physical survival, of individual humans is to take a big gamble. Cleopatra lost twice. Her relationship with Caesar ended on the Ides of March. She recovered from this setback, but once her second paramour turned out to be a busted flush, the game was up.

Antony even managed to botch his suicide, the sword missing his heart. It is unclear how the last Pharaoh ended her life, but we can be sure of one thing. The asp, or Egyptian cobra, had nothing to do with it. It is typically about eight feet long – rather large to hide in a basket of figs, as the most popular account of her death has it, and inconvenient to apply to the breast. However, whichever method of dying she chose, she could not escape the bitter reality that her astonishing career had been all in vain. Egypt lost its freedom, only regaining it in the 20th century.

The main problem facing the historian of the Roman Republic during its death throes in the first century BC is that there is an excess of material – too many events, too many dramatis personae, too much plot. So far as Hellenistic Egypt is concerned, this difficulty is exacerbated by the fact that nearly all the men are called Ptolemy and most of the women either Cleopatra or Arsinoe. It is almost impossible to draw a family tree of the ruling dynasty because they enthusiatically practiced incest; brother married sister, father daughter, uncle niece. The writer who simplifies will irritate the scholar, but too much information will bore the reader.

Stacy Schiff falls into the first category. Her life of Cleopatra is slightly soft-focused, as if she has applied Vaseline to the lens. It leaves the impression that, like a student taking an exam, she knows only a little more than what she writes. Sometimes she nods; to say, as she does, that Roman women were without legal rights is incorrect, although they were not allowed to hold political office. That said, she has done her homework and writes elegantly and wittily, creating truly evocative word pictures.

Her description of Alexandria teems with diverse life, whereas Adrian Goldsworthy gives an uninspiring account of the city. His prose fails to fly and uninstructed readers may occasionally get stuck in dense narrative thickets, but, a judicious scholar, he knows his subject backwards. Above all, Goldsworthy understands military matters. His battle of Actium is, rightly, no battle at all, but an attempt by Antony and Cleopatra to escape their doom by breaking out of a disastrous sea blockade; whereas Schiff is not much interested in boys' wargames and does less than justice to the tactical brilliance of Octavian's admiral, Agrippa. However, in their different ways, each of these authors has thrown light on the facts behind the legend, in so far as they can now be retrieved.

But who created the legend in the first place? None other than Octavian, later Rome's first emperor Augustus. He enjoyed the services of a talented public relations team (including two geniuses, the poets Virgil and Horace), which painted the completely inaccurate portrait of a noble Roman made effeminate by sexual passion and of an oriental queen who was little better than a whore. Opinion in Rome was duly shocked.

Posterity, in the form of another genius, William Shakespeare, cleaned up the story, overlaying lechery with love. Bathed in the glow of incomparable poetry, Antony and Cleopatra joined the immortals.

For those who have eyes to see, though, these books reveal the pair as the low, dishonest politicians they really were.

Anthony Everitt's life of Hadrian is published by Random House USA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments