Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

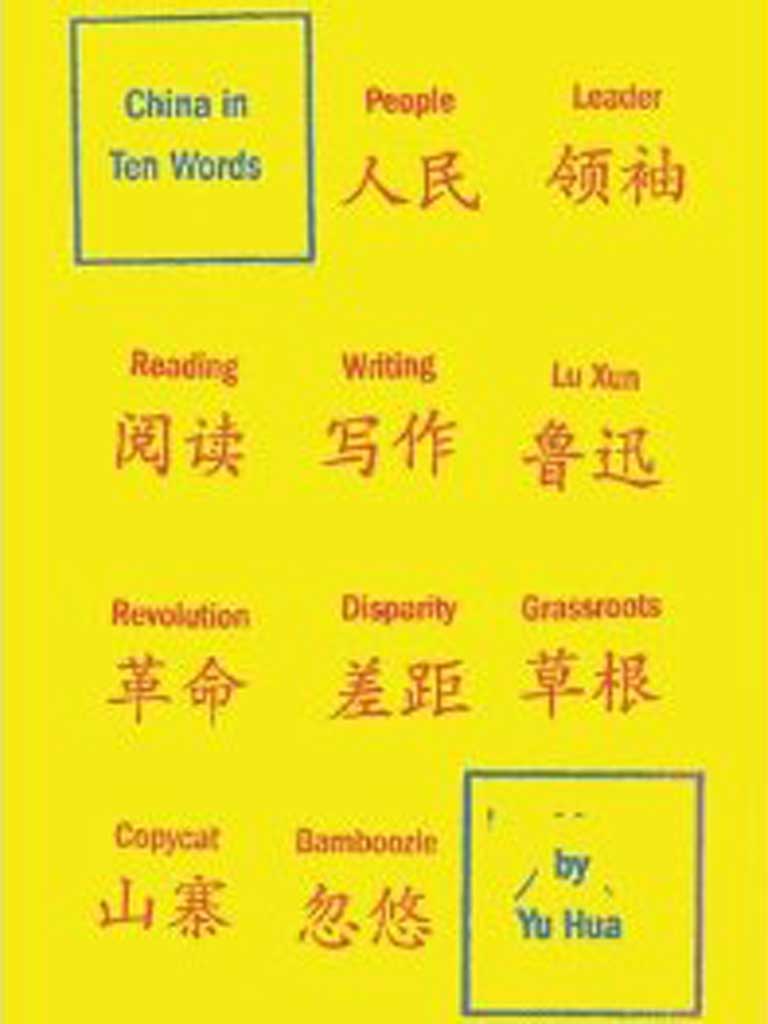

To tell the stories of China's gargantuan transformation in just ten words might seem a little quixotic. How could one capture the consequences of the fastest industrial revolution ever witnessed, in the world's most populous state? In these short, kaleidoscopic essays, novelist Yu Hua has done it, each word the prompt for personal memoir, contemporary reportage and sharp political commentary.

All writers love words, but few can have hungered for them like Yu. As he grew up during the Cultural Revolution, almost all books were banned. In "Reading", he describes a world in which the only texts to hand were the The Little Red Book and Mao's Selected Works. Both proved indigestible and flavourless. Undaunted, he subsisted on the intriguing tales buried in their footnotes.

Later, he graduated to illicitly circulating copies of Western classical novels. When he and his friend acquired, for only a day, a complete copy of a Dumas novel, they stayed up all night copying by hand. Just 30 years later, at a book fair in Beijing, he watched great piles of surplus books being flogged off by weight.

It is that great swing "from an era of material shortages to an era of extravagance and waste", that he explores in "Disparities". In his youth, disparities were minuscule and ideological – deviations from Mao's line that could make or break a life. Now they refer to the massive material inequalities that have emerged.

The complexity and fragility of the new order are best captured by "Copycat" and "Bamboozle". "Copycat" began as a hamlet surrounded by a stockade, became a hinterland of bandits, before mutating into imitation, beyond the law. The word now carries connotations of counterfeit, mischief and caricature. Originally, "bamboozle" meant to bob and sway, but acquired the sense of misleading, a con-trick or a rip-off. The word elides rank deceit with chicanery and pranks, and serves to "throw a cloak of respectability over deception and manufactured rumour".

In these pages, China appears to be a place where words can take on so many shades of meaning that they serve to obfuscate. We are lucky that Yu Hua hungered for them for so long; that he uses them with care, and to illuminate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments